SHAKESPEARE: THE BIRTH OF HUMANISM

|

Background: The

most influential writer in all of English literature, William Shakespeare was born

in 1564 to a successful middle-class glove-maker in

Stratford-upon-Avon, England. Shakespeare attended grammar school, but his formal

education proceeded no further. In 1582 he married an

older woman, Anne Hathaway, and had three children with her. Around 1590 he left his family behind and traveled to London to work as

an actor and playwright. Public and critical success quickly followed, and Shakespeare

eventually became the most popular playwright in England and part-owner of the Globe

Theater. His career bridged the reigns of Elizabeth I (ruled 1558–1603) and James I (ruled 1603–1625), and he was a favorite of both monarchs. Indeed, James

granted Shakespeare’s company the greatest possible compliment by bestowing upon its

members the title of King’s Men. Wealthy and renowned, Shakespeare retired to

Stratford and died in 1616 at the age of fifty-two. At the

time of Shakespeare’s death, literary luminaries such as Ben Jonson hailed his works

as timeless. Shakespeare’s

works were collected and printed in various editions in the century following his death,

and by the early eighteenth century his reputation as the greatest poet ever to write in

English was well established. The unprecedented admiration garnered by his works led to a

fierce curiosity about Shakespeare’s life, but the dearth of biographical information

has left many details of Shakespeare’s personal history shrouded in mystery. Some

people have concluded from this fact that Shakespeare’s plays were really written by

someone else—Francis Bacon and the Earl of Oxford are the two most popular

candidates—but the support for this claim is overwhelmingly circumstantial, and the

theory is not taken seriously by many scholars. In the absence of credible

evidence to the contrary, Shakespeare must be viewed as the author of the thirty-seven

plays and 154 sonnets that bear his name. The legacy of

this body of work is immense. A number of Shakespeare’s plays seem to have

transcended even the category of brilliance, becoming so influential as to profoundly

affect the course of Western literature and culture ever after. Written during the first

part of the seventeenth century (probably in 1600 or 1601), Hamlet was probably

first performed in July 1602. It was first published in

printed form in 1603 and appeared in an enlarged edition

in 1604. As was common practice during the sixteenth and

seventeenth centuries, Shakespeare borrowed for his plays ideas and stories from earlier

literary works. He could have taken the story of Hamlet from several possible sources,

including a twelfth-century Latin history of Denmark compiled by Saxo Grammaticus and a

prose work by the French writer François de Belleforest, entitled Histoires Tragiques. The raw material that

Shakespeare appropriated in writing Hamlet is the story of a Danish prince whose uncle

murders the prince’s father, marries his mother, and claims the throne. The prince

pretends to be feeble-minded to throw his uncle off guard, then manages to kill his uncle

in revenge. Shakespeare changed the emphasis of this story entirely, making his Hamlet a

philosophically-minded prince who delays taking action because his knowledge of his

uncle’s crime is so uncertain. Shakespeare went far beyond making uncertainty a

personal quirk of Hamlet’s, introducing a number of important ambiguities into the

play that even the audience cannot resolve with certainty. For instance, whether

Hamlet’s mother, Gertrude, shares in Claudius’s guilt; whether Hamlet continues

to love Ophelia even as he spurns her, in Act III; whether Ophelia’s death is suicide

or accident; whether the ghost offers reliable knowledge, or seeks to deceive and tempt

Hamlet; and, perhaps most importantly, whether Hamlet would be morally justified in taking

revenge on his uncle. Shakespeare makes it clear that the stakes riding on some of these

questions are enormous—the actions of these characters bring disaster upon an entire

kingdom. At the play’s end it is not even clear whether justice has been achieved. By modifying his source

materials in this way, Shakespeare was able to take an unremarkable revenge story and make

it resonate with the most fundamental themes and problems of the Renaissance. The

Renaissance is a vast cultural phenomenon that began in fifteenth-century Italy with the

recovery of classical Greek and Latin texts that had been lost to the Middle Ages. The

scholars who enthusiastically rediscovered these classical texts were motivated by an

educational and political ideal called (in Latin) humanitas—the idea that all of the

capabilities and virtues peculiar to human beings should be studied and developed to their

furthest extent. Renaissance humanism, as this movement is now called, generated a new

interest in human experience, and also an enormous optimism about the potential scope of

human understanding. Hamlet’s famous speech in Act II, “What a piece of work is

a man! How noble in reason, how infinite in faculty, in form and moving how express and

admirable, in action how like an angel, in apprehension how like a god—the beauty of

the world, the paragon of animals!” (II.ii.293–297) is directly based upon one of the major texts of the

Italian humanists, Pico della Mirandola’s Oration on

the Dignity of Man. For the humanists, the purpose of cultivating reason was to

lead to a better understanding of how to act, and their fondest hope was that the

coordination of action and understanding would lead to great benefits for society as a

whole. As the Renaissance spread

to other countries in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, however, a more skeptical

strain of humanism developed, stressing the limitations of human understanding. For

example, the sixteenth-century French humanist, Michel de Montaigne, was no less

interested in studying human experiences than the earlier humanists were, but he

maintained that the world of experience was a world of appearances, and that human beings

could never hope to see past those appearances into the “realities” that lie

behind them. This is the world in which Shakespeare places his characters. Hamlet is faced

with the difficult task of correcting an injustice that he can never have sufficient

knowledge of—a dilemma that is by no means unique, or even uncommon. And while Hamlet

is fond of pointing out questions that cannot be answered because they concern

supernatural and metaphysical matters, the play as a whole chiefly demonstrates the

difficulty of knowing the truth about other people—their guilt or innocence, their

motivations, their feelings, their relative states of sanity or insanity. The world of

other people is a world of appearances, and Hamlet

is, fundamentally, a play about the difficulty of living in that world. |

PLOT

OF HAMLET |

|

On

a dark winter night, a ghost walks the ramparts of Elsinore Castle in Denmark.

Discovered first by a pair of watchmen, then by the scholar Horatio, the ghost resembles

the recently deceased King Hamlet whose brother Claudius has inherited the throne and

married the king’s widow, Queen Gertrude. When Horatio and the watchmen bring Prince

Hamlet, the son of Gertrude and the dead king, to see the ghost, it speaks to him,

declaring ominously that it is indeed his father’s spirit, and that he was murdered

by none other than Claudius. Ordering Hamlet to seek revenge on the man who usurped his

throne and married his wife, the ghost disappears with the dawn. Prince Hamlet devotes

himself to avenging his father’s death, but, because he is contemplative and

thoughtful by nature, he delays, entering into a deep melancholy and even apparent

madness. Claudius and Gertrude worry about the prince’s erratic behavior and attempt

to discover its cause. They employ a pair of Hamlet’s friends, Rosencrantz and

Guildenstern, to watch him. When Polonius, the pompous Lord Chamberlain, suggests that

Hamlet may be mad with love for his daughter, Ophelia, Claudius agrees to spy on Hamlet in

conversation with the girl. But though Hamlet certainly seems mad, he does not seem to

love Ophelia: he orders her to enter a nunnery and declares that he wishes to ban

marriages. A group of traveling

actors comes to Elsinore, and Hamlet seizes upon an idea to test his uncle’s guilt.

He will have the players perform a scene closely resembling the sequence by which Hamlet

imagines his uncle to have murdered his father, so that if Claudius is guilty, he will

surely react. When the moment of the murder arrives in the theater, Claudius leaps up and

leaves the room. Hamlet and Horatio agree that this proves his guilt. Hamlet goes to kill

Claudius but finds him praying. Since he believes that killing Claudius while in prayer

would send Claudius’s soul to heaven, Hamlet considers that it would be an inadequate

revenge and decides to wait. Claudius, now frightened of Hamlet’s madness and fearing

for his own safety, orders that Hamlet be sent to England at once. Hamlet goes to confront

his mother, in whose bedchamber Polonius has hidden behind a tapestry. Hearing a noise

from behind the tapestry, Hamlet believes the king is hiding there. He draws his sword and

stabs through the fabric, killing Polonius. For this crime, he is immediately dispatched

to England with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. However, Claudius’s plan for Hamlet

includes more than banishment, as he has given Rosencrantz and Guildenstern sealed orders

for the King of England demanding that Hamlet be put to death. In the aftermath of her

father’s death, Ophelia goes mad with grief and drowns in the river. Polonius’s

son, Laertes, who has been staying in France, returns to Denmark in a rage. Claudius

convinces him that Hamlet is to blame for his father’s and sister’s deaths. When

Horatio and the king receive letters from Hamlet indicating that the prince has returned

to Denmark after pirates attacked his ship en route to England, Claudius concocts a plan

to use Laertes’ desire for revenge to secure Hamlet’s death. Laertes will fence

with Hamlet in innocent sport, but Claudius will poison Laertes’ blade so that if he

draws blood, Hamlet will die. As a backup plan, the king decides to poison a goblet, which

he will give Hamlet to drink should Hamlet score the first or second hits of the match.

Hamlet returns to the vicinity of Elsinore just as Ophelia’s funeral is taking place.

Stricken with grief, he attacks Laertes and declares that he had in fact always loved

Ophelia. Back at the castle, he tells Horatio that he believes one must be prepared to

die, since death can come at any moment. A foolish courtier named Osric

arrives on Claudius’s orders to arrange the fencing match between Hamlet and Laertes. The sword-fighting begins.

Hamlet scores the first hit, but declines to drink from the king’s proffered goblet.

Instead, Gertrude takes a drink from it and is swiftly killed by the poison. Laertes

succeeds in wounding Hamlet, though Hamlet does not die of the poison immediately. First,

Laertes is cut by his own sword’s blade, and, after revealing to Hamlet that Claudius

is responsible for the queen’s death, he dies from the blade’s poison. Hamlet

then stabs Claudius through with the poisoned sword and forces him to drink down the rest

of the poisoned wine. Claudius dies, and Hamlet dies immediately after achieving his

revenge. At this moment, a

Norwegian prince named Fortinbras,

who has led an army to Denmark and attacked Poland earlier in the play, enters with

ambassadors from England, who report that Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are dead.

Fortinbras is stunned by the gruesome sight of the entire royal family lying sprawled on

the floor dead. He moves to take power of the kingdom. Horatio, fulfilling Hamlet’s

last request, tells him Hamlet’s tragic story. Fortinbras orders that Hamlet be

carried away in a manner befitting a fallen soldier. |

On

Shakespeare Murdoch (29) speaks of great writers possessing a

“calm merciful vision” because they accept difference in people and understand

why they are so. Tolerance is based on exercising the imagination, putting oneself into

centers of reality that are far from oneself. I

agree with Murdoch when she says that in Shakespeare and Homer we are bathed in an

intelligent concern, a generosity of spirit and tolerance that warms us each time we read. They seem to be saying to us that they so loved

the world and cared to such a degree about the people and their impossibly absurd and

bloody struggles within it, that they were willing to give of themselves to an equal

degree to convey their vision. There is no

need in great writers to remake the world in their image; often the artist is drawn to

what is “other” than himself. Murdoch (30) feels that this type of merciful

objectivity is similar to virtue. The canon

in literature today is frequently discredited for its sexist, racist or other biased

“norms”. Even Shakespeare has

not escaped; serious doubts about his choice of words at the ending of Taming of the

Shrew have been voiced. (Lyas 210). However, he is far from the worst. The result has been for many artists today to

mistrust any claim to authority by the “masters”. Because the classics in literature have been

labelled by centuries of experts as the “best”, they are seen as needing to be

torn down and exposed for embracing a flawed value system.

In other words, some artists feel the moral universe of these works no

longer applies to modern life. Murdoch (236)

adds to this by saying “traditional art is seen as far too grand, and is then

seen as a half-truth”. Quality art, however, constantly recreates itself

through returning to plain speech, unpretentious truths and ordinary life. Art tells the truth by including the absurd and

the simple. The best art is its own internal

critic, recognizing and celebrating the absurd complexity and the incompleteness of its

form. And here we find the great paradox

– the best tragedy is anti-tragic. King

Lear wants to embody the hyperbolic, histrionic drama of his position. Shakespeare forces him to enact the true tragic,

the absurd and incompleteness of being a flawed human being. (Murdoch 240). There is no easy way out with good literature. In life as in fiction, there is the affront of

death, its “intractable constancy”, as Steiner (140) calls it. The fact of death is resistant to reason. It is in literature that we rehearse for our

meetings with death. And through the metaphor

of the resurrection, the literary means of overcoming death, we find something beyond it. In the lucid intensity of meeting death, the

aesthetic form pushes back and generates a response which says, there is still life, a

vitality, a perseverance that counters the fact of it all by pointing out that one life

may have ended, but somewhere, somehow, life goes on. (141). Let me summarize what the challenge of literature is

then. When faced with our unqualified

aloneness we feel compelled to reach out to the “other”. There is irony here; while recognizing the

strangeness of others, literature invites us to withhold judgment until we have discerned

the separate and qualitative uniqueness of the other.

After we have opened ourselves up, we have a chance to see ourselves in

them. As we take something from the otherness

in characters, we also give to real people. It

is one way of transcending death, by becoming part of the larger realm of life. Murdoch repeats that literature commands us to

conquer self-absorption, and one way to do this is through beauty, which in a

disinterested state of mind, allows us to perceive beyond ourselves. “Then the ‘otherness’ which enters

into us makes us ‘other’”. (Steiner

188). The challenge is to let go ourselves in

order to become something better. Art, and especially literature, are the most practically

important things for our survival and salvation, Murdoch (241) claims. Words that are refined and exact represent the

most vibrant texture and “stuff” of our moral being. They are the most universally used and understood

way we express ourselves into existence. Words

alone make distinctions, and with words, great literature stands up and declares that some

things are worth believing in. The level of a

civilization is ultimately measured by its ability to use words, and through words reveal

the truth. Literature enlarges our ability to

exist through words, and in the battle for higher civilization, with its freedom and

justice, our best weapons against alienating scientific jargon, mainstreaming journalism

and tyrannical mystification are truth and clarity. (242). I would like to look more closely now at the best we have. If we try to tear away the mysterious veils of writing, what exactly makes Shakespeare so extraordinary? How did he bring the concept of what it is to be human into a more deeply understood existence? For one thing, there is his command of language, the dazzling metaphors, newly invented expressions, and his usage of language. For Shakespeare, the meaning of a word is always another word, and words can be like persons. Each of Shakespeare’s characters speaks in his or her own voice. Bloom (64) states, “his uncanny ability to present consistent and different actual-seeming voices of imaginary beings stems in part from the most abundant sense of reality ever to invade literature.” Another example is in the stories themselves. Much has been said about Shakespeare’s free borrowing from historical texts (i.e., Pliny) and existing medieval plays, but the fact remains that what he took, he took much further. It is his ability to absorb and redeploy that is striking. What seems like a paradox of imitation resulted in a profound originality. (Bantock/Abbs 148). Another reason for the unusual superiority of Shakespeare is in “his power of representation of human personalities and their mutabilities.” (Bloom, 63). As we have said, with Hamlet, Shakespeare for the first time in literature has a character overhear himself as he speaks and he is able to learn from himself. Hegel remarked that Hamlet and the great villains, Iago and Edmund, are artists of the self, or free artists of themselves, able to go on creating more and more dimensions of themselves. (64). The difficulty of interpreting Hamlet, the most fecund of characters, is partly due to limitations within ourselves. Shakespeare is able to supply more contexts for explaining us than we are capable of supplying for his characters. When we write we must tunnel into our consciousness to locate the proper word, phrase or inference that connects memory and sense with the universal. The equilibrium between precision of image and multiple meanings is the secret of making those important associations. If we note when this is successful in literature, we recognize that it is the words that resonate within ourselves, which are intimate and feel like deja vu or identification. (Steiner 184). We return to the books that reach the deepest parts of ourselves. There is no way to defend a personal canon; it just eventually becomes who we are. As our writing progresses a literary image of ourselves sharpens. The more we write, the more clearly patterns emerge. We are drawn to those defining moments in literature that correspond most closely to our own lives, ones that we are able to write about most strongly. These become the themes or subjects that exert the greatest hold over our imaginations. F. Scott Fitzgerald admitted he was writing the same story over and over; trying each time to get it down just right, go a little deeper so it might be possible to understand it better. Hughes (Winter Pollen 106) claims that even Shakespeare wrote out of a single idea that doggedly tracked down a certain sexual dilemma that was rooted in his concept of good and evil, power and weakness. In his case, it was hardly limiting; the singleness of that idea was all-inclusive and affected nearly all of his best works. It was the way his imagination unraveled the mystery of himself to himself. Depending on how well we’ve ingested

our reading, we may be able to ascribe certain attitudes we hold to those found in

literature. In fact, it may no longer be

possible to remember which came first, our real life experience or that which occurred in

something we read. According to the level of

our familiarity with novels, we may conceive of love in the manner of Jack and Jill, Romeo

and Juliet, or Natasha. Our jealousies

may imitate Othello’s; Lear becomes a model when our children repay us with silence

or retribution. (Steiner 194).

Shakespeare

and Education

In an ideal world, students come to school hungry for knowledge, eager to improve their minds. In reality, they ask, why should I study Shakespeare? Only 25% will go on to higher education, fewer still will go into the arts or even attend cultural events. An underlying problem for education today is that there are too many distractions, too many easy entertainments. Young people are able to access a wealth of pop culture outside of class but where will they get “high” culture if not in school? If we take, for example, teaching Shakespeare, the concern in modern education is that there has been a shift from the bard’s mass appeal to the elite, or that his plays have moved from the Dionysian camp into Apollo’s. (Aspin/Abbs 254). Instead of an audience comprised of the groundlings up to the royal boxes, today there is a growing belief in the inaccessibility of Shakespeare, the language being too difficult, too archaic, or a fear of pupils not understanding. Shakespeare has come to be associated with high culture, snobbery and an aesthetic initiation that many people believe they do not possess. But now more than ever we must introduce students to Shakespeare because it is in his work that students can tap deep springs of feeling and human drama. They will find to their delight that their encounter is intense and exciting. (Gibson/Abbs 60). When students are asked to take “feelings” as a subject of study, they are initiated into the refinement and control of emotions, and again, with Aristotle, we can say that Shakespeare’s plays allow for their safe exercise and release. We think of how our view of the suffering of others is altered once we have felt the “storm upon our heads”, sympathetically entering into the experience of the “other”, and avoiding what Gloucester describes as the indifferent and comfortable man, “who will not see because he does not feel” (King Lear, IV, 1/Knights/Abbs 62). Shakespeare invites us to try on fictional personalities in particular situations and learn through our moral imagination. Another argument in education today is the

idea of letting students bring what is most “relevant” to their lives into the

classroom; if that happens to be “Sponge Bob” or “Survivor”, then so

be it. But I would strongly argue for

supplying the challenges needed to develop more complex thinkers, if only to begin to

discern the intentions of propaganda and sort out thorny moral questions. This effort may not be viewed as worthwhile to the

students at this point in their lives, being perhaps due to a lack of maturity or

sophistication, but if it can be seen as an investment in their intellectual future, it is

likely to pay off later. For there often

comes a time a few years ahead when the older student will want to know how Uncle

Tom’s Cabin sparked the war that ended slavery or why Hamlet may be

the best piece of literature ever written. It

is a seed that must be planted while there is still a chance for the student to be guided

and familiarized with difficult material. One

day she will be more willing to return to it, because it is not cold to her, not entirely

unknown, but she has an idea of how to proceed. She

has been here before. “The readiness is

all.” It is one more step that can be

taken to improve life and her understanding of it when she chooses. (excerpt from

Barber, The Immediacy of Writing.) |

|

|

Meanwhile, back on the Continent, the Renaissance was flowering.... |

|

|

|

Mona Lisa |

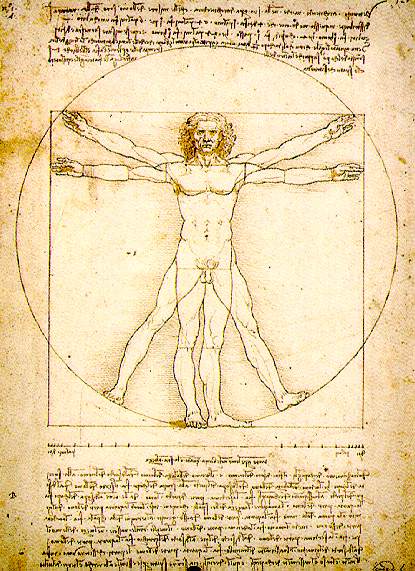

The Proportions of the Human Figure |

| Leonardo da Vinci | (from: http:// WebMuseum: Leonardo da Vinci ) |