Background

on

Postmodernism

What started it all in art:

Michel Duchamp's Fountain

|

|

Postmodernism is a term applied to a wide-ranging set of

developments in critical theory, philosophy, architecture, art, literature,

religion, and culture,

which are generally characterized as either emerging from, in reaction to, or superseding,

modernism.

In architecture, art, music and literature,

postmodernism is a name for many stylistic reactions to, and developments from, modernism. Postmodern

style is often characterized by eclecticism, digression, collage, pastiche, and irony. Some artistic movements

commonly called postmodern are pop art, architectural deconstructivism,

magical

realism in literature, maximalism, and neo-romanticism.

Postmodern theorists see postmodern art as a conflation or reversal of well-established

modernist systems, such as the roles of artist versus audience, seriousness versus play,

or high culture

versus kitsch.

In sociology,

postmodernism is described as the result of economic, cultural, and demographic

changes. These changes include the rise of the service

economy, the importance of the mass media, and the rise of an increasingly interdependent world

economy. Related terms in this context include post-industrial society, late

capitalism, information age, globalization,

and global

village. (See also Postmodern and Media theory).

As a cultural

movement, postmodernism is an aspect of postmodernity,

which is broadly defined as the condition of Western society after modernity. The

adjective postmodern can refer to aspects of either postmodernism or postmodernity.

According to postmodern theorist Jean-François

Lyotard, postmodernity is characterized as an "incredulity toward metanarratives",

meaning that in the era of postmodern culture, people have rejected the grand, supposedly

universal stories and paradigms

such as religion, conventional philosophy, capitalism and gender that have defined culture

and behavior in the past, and have instead begun to organize their cultural life around a

variety of more local and subcultural ideologies, myths and stories. Furthermore, it promotes the idea that

all such metanarratives and paradigms are stable only while they fit the available

evidence, and can potentially be overturned when phenomena occur that the paradigm cannot

account for, and a better explanatory model (itself subject to the same fate) is found.

See La Condition postmoderne: Rapport sur le savoir (The Post Modern Condition:

A Report on Knowledge) in 1979,

and the results of acceptance of postmodernism is the view that different realms of

discourse are incomensurable and incapable of judging the results of other discourse, a

conclusion he drew in La Differend (1983).

In philosophy, where

the term is extensively used, it applies to movements that include post-structuralism,

deconstruction,

multiculturalism,

gender

studies and literary theory, sometimes called simply "theory".

It emerged beginning in the 1950s as a critique of doctrines such as positivism and

emphasizes the importance of power relationships, personalization and discourse in the

"construction" of truth and world views. In this context it has been used by

many critical

theorists to assert that postmodernism is a break with the artistic and philosophical

tradition of the Enlightenment, which they characterize as a quest for an

ever-grander and more universal system of aesthetics, ethics, and knowledge. They

present postmodernism as a radical criticism of Western

philosophy. Postmodern philosophy draws on a number of approaches to

criticize Western thought, including historicism, and psychoanalytic

theory.

The term postmodernism

is also used in a broader pejorative sense to describe attitudes, sometimes part of the

general culture, and sometimes specifically aimed at postmodern critical theory, perceived

as relativist, nihilist, counter-Enlightenment

or antimodern,

particularly in relationship to critiques of rationalism, universalism, or

science. It is also

sometimes used to describe social changes which are held to be antithetical to traditional

systems of morality,

particularly by evangelical Christians.

The role, proper usage, and meaning of postmodernism

are matters of intense debate and vary widely with context.

|

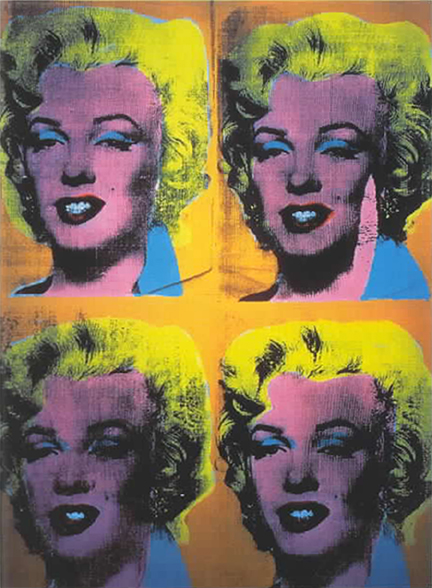

Andy Warhol - 4

Marilyns |

The

development of postmodernism

Features of

postmodern culture begin to arise in the 1920s with the emergence of the dada movement, which featured

collage and a focus on the framing of objects and discourse as being as important, or more

important, than the work itself. Another strand which would have tremendous impact on

post-modernism would be the existentialists, who placed the centrality of the individual

narrative as being the source of morals and understanding. Einstein's theories and the

rise of quantum physics began undermining the view of science as objective truth and lent

scientific support to postmodern notions of subjective truth. However, it is with the end

of the Second

World War that recognizably post-modernist attitudes begin to emerge.

Central to

these is the focusing on the problems of any knowledge which is

founded on anything external to an individual. Post-modernism, while widely diverse in its forms,

almost invariably begins from the problem of knowledge which is broadly disseminated in

its form, but not limited in its interpretation. Post-modernism rapidly developed a

vocabulary of anti-enlightenment rhetoric, used to argue that rationality was neither as

sure or as clear as rationalists supposed, and that knowledge was inherently linked to

time, place, social position and other factors from which an individual constructs

their view of knowledge. To escape from constructed knowledge, it then becomes necessary

to critique it, and thus deconstruct the asserted knowledge. Jacques

Derrida argued that to defend against the inevitable self-deconstruction of knowledge,

systems of power, called hegemony

would have to postulate an original utterance, the logos. This

"privileging" of an original utterance is called "logocentrism".

Instead of rooting knowledge in particular utterances, or "texts", the basis of

knowledge was seen to be in the free play of discourse itself, an idea rooted in Wittgenstein's

idea of a language game. This emphasis on the allowability of free play within the context

of conversation and discourse leads postmodernism to adopt the stance of irony, paradox,

textual manipulation, reference and tropes.

Armed with this

process of questioning the social basis of assertions, postmodernist philosophers began to

attack unities of modernism, and particularly unities seen as being rooted in the Enlightenment.

Since Modernism had

made the Enlightenment a central source of its superiority over the Victorian and Romantic periods,

this attack amounted to an indirect attack on the establishment of modernism itself.

Perhaps the most striking examples of this skepticism are to be found in the works of

French cultural theorist, Jean Baudrillard. In his book Simulacra and Simulation,

he contends that social 'reality' no longer exists in the conventional sense, but has been

supplanted by an endless procession of simulacra. The mass media, and other forms of mass cultural

production, generate constant re-appropriation and re-contextualisation of familiar

cultural symbols and images, fundamentally shifting our experience away from 'reality', to

'hyperreality'.

Postmodernism

therefore has an obvious distrust toward claims about truth, ethics, or beauty being

rooted in anything other than individual perception and group construction. Utopian ideals of

universally applicable truths or aesthetics give way to provisional, decentered, local petit

recits which, rather than referencing an underlying universal truth or aesthetic, point

only to other ideas and cultural artifacts, themselves subject to interpretation and

re-interpretation. The "truth", since it can only be understood by all of its

connections is perpetually "deferred", never reaching a point of fixed knowledge

which can be called "the truth."

Postmodernism

is often used in a larger sense, meaning the entire trend of thought in the late 20th

century, and the social and philosophical realities of that period. Marxist critics argue

that post-modernism is symptomatic of "late capitalism" and the decline of

institutions, particularly the nation-state. Other thinkers assert that post-modernity is

the natural reaction to mass broadcasting and a society conditioned to mass production and

mass political decision making. The ability of knowledge to be endlessly copied defeats

attempts to constrain interpretation, or to set "originality" by simple means

such as the production of a work. From this perspective, the schools of thought labelled

"postmodern" are not as widely at odds with their time period as the polemics

and arguments appear, pointing, for example, to the shift of the basis of scientific

knowledge to a provisional consensus of scientists, as posited by Thomas Kuhn.

Post-modernism is seen, in this view, as being conscious of the nature of the

discontinuity between modern and post-modern periods which is generally present.

Postmodernism

has manifestations in many modern academic and non-academic disciplines: philosophy, theology, art, architecture, film, television, music, theatre, sociology, fashion, technology, literature, and

communications are all heavily influenced by postmodern trends and ideas, and are

thoroughly scrutinised from postmodern perspectives. Crucial to these are the denial of

customary expectations, the use of non-orthogonal angles in buildings such as the work of Frank Gehry, and

the shift in arts exemplified by the rise of minimalism in art

and music. Post-modern philosophy often labels itself as critical

theory and grounds the construction of identity in the mass media.

Postmodernism

was first identified as a theoretical discipline in the 1980s, but as a cultural

movement it predates them by many years. Exactly when modernism began to give way to

postmodernism is difficult to pinpoint, if not simply impossible. Some theorists reject

that such a distinction even exists, viewing postmodernism, for all its claims of

fragmentation and plurality, as still existing within a larger 'modernist' framework. The

philosopher Jürgen

Habermas is a strong proponent of this view, which has aspects of a lumpers/splitters

problem: is the entire 20th century one period, or two distinct periods?

The theory

gained some of its strongest ground early on in French academia. In 1979 Jean-François

Lyotard wrote a short but influential work The Postmodern Condition : a report

on knowledge. Jean Baudrillard, Michel

Foucault, and Roland Barthes (in his more post-structural work) are also

strongly influential in postmodern theory. Postmodernism is closely allied with several

contemporary academic disciplines, most notably those connected with sociology. Many of

its assumptions are integral to feminist and post-colonial

theory.

Some identify

the burgeoning anti-establishment movements of the 1960s as the earliest trend

out of cultural modernity toward postmodernism.

Tracing it

further back, some identify its roots in the breakdown of Hegelian idealism, and the

impact of both World Wars (perhaps even the concept of a World War). Heidegger

and Derrida

were influential in re-examining the fundamentals of knowledge, together with the work of Ludwig

Wittgenstein and his philosophy of action, Soren

Kierkegaard's and Karl

Barth's important fideist approach to theology, and even the nihilism of Nietzsche's

philosophy. Michel

Foucault's application of Hegel to thinking about the body is also

identified as an important landmark. While it is rare to pin down the specific origins of

any large cultural shift, it is fair to assume that postmodernism represents an

accumulated disillusionment with the promises of the Enlightenment project and its

progress of science, so central to modern thinking.

The movement

has had diverse political ramifications: its anti-ideological insights appear conducive

to, and strongly associated with, the feminist movement, racial equality movements, gay rights movements,

most forms of late 20th century anarchism, even the peace movement

and various hybrids of these in the current anti-globalization movement. Unsurprisingly, none

of these institutions entirely embraces all aspects of the postmodern movement, but

reflect or, in true postmodern style, borrow from some of its core ideas.

Also, many cite

Charles

Jencks' 1977 "The

Language of Postmodern Architecture" among the earliest works which shaped the use of

the term today.

|

Multicolor Snakeskin

Hood - MMA |

Postmodernism's

manifestations

Postmodernism

in language

Postmodern

philosophers are often regarded as difficult to read, and the critical theory that has

sprung up in the wake of postmodernism has often been ridiculed for its stilted syntax and

attempts to combine polemical tone and a vast array of new coinages. However, similar

charges could be levelled at the works of previous eras, such as the works of Immanuel Kant,

as well as at the entire tradition of Greek thought in antiquity.

More important

to postmodernism's role in language is the focus on the implied meaning of words and

forms, the power structures that are accepted as part of the way words are used, from the

use of the word "Man" with a capital "M" to refer to the collective

humanity, to the default of the word "he" in English as a pronoun for a person

of gender unknown to the speaker, or as a casual replacement for the word "one".

This, however, is merely the most obvious example of the changing relationship between

diction and discourse which postmodernism presents.

An important

concept in postmodernism's view of language is the idea of "play". In the

context of postmodernism, play means changing the framework which connects ideas, and thus

allows the troping, or turning, of a metaphor or word from one context to another, or from

one frame of reference to another. Since, in postmodern thought, the "text" is a

series of "markings" whose meaning is imputed by the reader, and not by the

author, this play is the means by which the reader constructs or interprets the text, and

the means by which the author gains a presence in the reader's mind. Play then involves

invoking words in a manner which undermines their authority, by mocking their assumptions

or style, or by layers of misdirection as to the intention of the author. This view of writing is not without harsh

detractors, who regard it as needlessly difficult and obscure.

Postmodernism

in art

Where

modernists hoped to unearth universals or the fundamentals of art, postmodernism aims to

unseat them, to embrace diversity and contradiction. A postmodern approach to art thus

rejects the distinction between low and high art forms. It rejects rigid genre boundaries

and favors eclecticism, the mixing of ideas and forms. Partly due to this rejection, it

promotes parody, irony, and playfulness,

commonly referred to as jouissance by postmodern theorists. Unlike modern art,

postmodern art does not approach this fragmentation as somehow faulty or undesirable, but

rather celebrates it. As the gravity of the search for underlying truth is relieved, it is

replaced with 'play'. As postmodern icon David Byrne, and his band Talking Heads said:

'Stop making sense'.

Post-modernity,

in attacking the perceived elitist approach of Modernism, sought greater connection with

broader audiences. This is often labelled 'accessibility' and is a central point of

dispute in the question of the value of postmodern art. It has also embraced the mixing of

words with art, collage and other movements in modernity, in an attempt to create more

multiplicity of medium and message. Much of this centers on a shift of basic subject

matter: postmodern artists regard the mass media as a fundamental subject for art, and use

forms, tropes, and materials - such as banks of video monitors, found art, and depictions

of media objects - as focal points for their art. Andy Warhol is an

early example of postmodern art in action, with his appropriation of common popular

symbols and "ready-made" cultural artifacts, bringing the previously mundane or

trivial onto the previously hallowed ground of high art.

Postmodernism's

critical stance is interlinked with presenting new appraisals of previous works. As

implied above the works of the "Dada" movement received greater attention, as

did collagists such as Robert Rauschenberg, whose works were initially considered

unimportant in the context of the modernism of the 1950s, but who, by the 1980s, began to be seen as

seminal. Post-modernism also elevated the importance of cinema in artistic discussions,

placing it on a peer level with the other fine arts. This is both because of the blurring

of distinctions between "high" and "low" forms, and because of the

recognition that cinema represented the creation of simulacra which was later duplicated

in the other arts.

Postmodernism

in literature

Main article

Postmodern

literature

Postmodern

literature argues for expansion, the return of reference, the celebration of fragmentation

rather than the fear of it, and the role of reference itself in literature. While drawing

on the experimental tendencies of authors such as James Joyce and Virginia Woolf

in English, and Borges in

Spanish, who were taken as influences by American postmodern works by authors such as Thomas Pynchon,

John Barth, Don Delillo, David

Foster Wallace and Paul Auster, the advocates of post-modern literature argue that

the present is fundamentally different from the modern period, and therefore requires a

new literary sensibility.

Deconstruction

Main

article: Deconstruction

Deconstruction

is an important textual "occurrence" described and analyzed by many postmodern

authors and philosophers,

beginning with Jacques Derrida, who coined the term. Deconstruction has to do

with the way in which the "deeper" substance of text opposes the text's more

"superficial" form. As a result of deconstruction, according to Derrida, texts

have multiple meanings, and the "violence" between the different meanings of

text may be elucidated by close textual analysis.

Popularly,

close textual analyses describing deconstruction within a text are often themselves called

deconstructions; as envisioned by Derrida, however, deconstruction was not a method

or a tool, but an occurrence within the text itself. Writings about deconstruction are

perhaps more aptly referred to as deconstructive readings.

Deconstruction

is far more important to postmodernism than its seemingly narrow focus on text

might imply. According to Derrida, one consequence of deconstruction is that text may be

defined so broadly as to encompass not just written words, but the entire spectrum of symbols and phenomena within

Western thought. To Derrida, a result of deconstruction is that no Western philosopher has

been able to successfully escape from this large web of text and reach the purely

text-free "signified" which they imagined to exist "just beyond" the

text.

Postmodernism

in philosophy

Main

article: Postmodern philosophy

Many figures in

the 20th century philosophy of mathematics are identified as

"postmodern" due to their rejection of mathematics as a

strictly neutral point of view. Some figures in the philosophy

of science, especially Thomas Samuel Kuhn and David Bohm, are also

so viewed. Some see the ultimate expression of postmodernism in science and mathematics in

the cognitive science of mathematics, which seeks

to characterize the habit of mathematics itself as strictly human, and based in human cognitive bias.

The term "Neo-liberalism"

has been used in a theological sense (http://www.adrian.warnock.info/2004/12/why-neo-liberal.htm,)

as a drive to deliberately modify the beliefs and practices of the church (especially evangelical) to

conform to post-modernism

Postmodernism

and post-structuralism

In terms of

frequently cited works, postmodernism and post-structuralism overlap quite significantly.

Some philosophers, such as Francois Lyotard, can legitimately be classified into both

groups. This is partly due to the fact that both modernism and structuralism owe much to

the Enlightenment project.

Structuralism

has a strong tendency to be scientific in seeking out stable patterns in observed

phenomena - an epistemological attitude which is quite compatible with Enlightenment

thinking, and incompatible with postmodernists. At the same time, findings from

structuralist analysis carried a somewhat anti-Enlightenment message, revealing that

rationality can be found in the minds of 'savage' people, just in forms differing from

those that people from 'civilized' societies are used to seeing. Implicit here is a

critique of the practice of colonialism, which was partly justified as a 'civilizing' process

by which wealthier societies bring knowledge, manners, and reason to less 'civilized'

ones.

Post-structuralism,

emerging as a response to the structuralists' scientific orientation, has kept the cultural

relativism in structuralism, while discarding the scientific orientations.

One clear

difference between postmodernism and poststructuralism is found in their respective

attitudes towards the demise of the project of the Enlightenment: post-structuralism is

fundamentally ambivalent, while postmodernism is decidedly celebratory.

Another

difference is the nature of the two positions. While post-structuralism is a position in

philosophy, encompassing views on human beings, language, body, society, and many other

issues, it is not a name of an era. Post-modernism, on the other hand, is closely

associated with "post-modern" era, a period in the history coming after the

modern age.

Postmodernity

and digital communications

Technological

utopianism is a common trait in Western history - from the 1700s when Adam Smith

essentially labelled technological progress as the source of the Wealth of Nations,

through the novels of Jules Verne in the late 1800s, through Winston

Churchill's belief that there was little an inventor could not achieve. Its

manifestation in the post-modernity was first through the explosion of analog mass

broadcasting of television. Strongly associated with the work of Marshall

McLuhan who argued that "the medium is the message", the ability of mass

broadcasting to create visual symbols and mass action was seen as a liberating force in

human affairs, even at the same time others were calling television "a vast

wasteland".

The second wave

of technological utopianism associated with post-modern thought came with the introduction

of digital internetworking, and became identified with Esther Dyson and

such popular outlets as Wired Magazine. According to this view digital communications

makes the fragmentation of modern society a positive feature, since individuals can seek

out those artistic, cultural and community experiences which they regard as being correct

for themselves.

The common

thread is that the fragmentation of society and communication gives the individual more

autonomy to create their own environment and narrative. This links into the post-modern

novel, which deals with the experience of structuring "truth" from fragments.

Postmodernism

and its critics

The term postmodernism

is often used pejoratively to describe tendencies perceived of as Relativist, Counter-enlightenment

or antimodern.

Particularly in relationship to critiques of Rationalism, Universalism or Science. Sometimes used to

describe tendencies in the society which are held to be antithetical to traditional

systems of morality,

particularly by Evangelical Christians.

Charles Murray,

a strong critic of postmodernism, defines the term:

"By contemporary intellectual fashion, I am referring to

the constellation of views that come to mind when one hears the words multicultural,

gender, deconstruct, politically correct, and Dead White

Males. In a broader sense, contemporary intellectual fashion encompasses as well the

widespread disdain in certain circles for technology and the scientific method. Embedded

in this mind-set is hostility to the idea that discriminating judgments are appropriate in

assessing art and literature, to the idea that hierarchies of value exist, hostility to

the idea that an objective truth exists. Postmodernism is the overarching label that is

attached to this perspective." [1]

Though Murray's

arguments against postmodernism are far from facile, critics have cautioned that Murray's

own work in The Bell Curve arrives at racially-charged conclusions

through research and argumentation that may not live up to the standards he defends.

One example is

the figure of Harold

Bloom, who has simultaneously been hailed as being against multiculturalism

and contemporary "fads" in literature, and also placed as an important figure in

postmodernism. If even the critics cannot keep score as to which side of a supposedly

clear line figures stand on, the best conclusion that can be drawn is that conclusions

about membership in the post-modern club are provisional.

Central to the

debate is the role of the concept of "objectivity" and what it means. In the

broadest sense, denial of objectivity is held to be the post-modern position, and a

hostility towards claims advanced on the basis of objectivity its defining feature. It is

this underlying hostility toward the concept of objectivity,

evident in many contemporary critical theorists, that is the common point of attack for

critics of postmodernism. Many critics characterise postmodernism as an ephemeral

phenomenon that cannot be adequately defined simply because, as a philosophy at least,

it represents nothing more substantial than a series of disparate conjectures allied only

in their distrust of modernism.

This antipathy

of postmodernists towards modernism, and their consequent tendency to define themselves

against it, has also attracted criticism. It has been argued that modernity was not

actually a lumbering, totalizing monolith at all, but in fact was itself dynamic and

ever-changing; the evolution, therefore, between 'modern' and 'postmodern' should be seen

as one of degree, rather than of kind - a continuation rather than a 'break'. One theorist

who takes this view is Marshall Berman, whose book All That is Solid Melts into

Air (a quote from Marx)

reflects in its title the fluid nature of 'the experience of modernity'.

As noted above

(see History of postmodernism), some theorists such as Habermas even argue that the

supposed distinction between the 'modern' and the 'postmodern' does not exist at all, but

that the latter is really no more than a development within a larger, still-current,

'modern' framework. Many who make this argument are left

academics with Marxist

leanings, such as Terry Eagleton, Fredric

Jameson, and David Harvey (social geographer), who are

concerned that postmodernism's undermining of Enlightenment values makes a progressive

cultural politics difficult, if not impossible. How can we effect any change in people's

poor living conditions, in inequality and injustice, if we don't accept the validity of

underlying universals such as the 'real world' and 'justice' in the first place? How is

any progress to be made through a philosophy so profoundly skeptical of the very notion of

progress, and of unified perspectives? The critics charge that the postmodern vision of a

tolerant, pluralist society in which every political ideology is perceived to be as valid,

or as redundant, as the other; may ultimately encourage individuals to lead lives of a

rather disastrous apathetic quietism. This reasoning leads Habermas to compare

postmodernism with conservatism and the preservation of the status quo.

Such critics

often argue that, in actual fact, such postmodern premises are rarely, if ever, actually

embraced — that if they were, we would be left with nothing more than a crippling

radical subjectivism. That the projects of the Enlightenment

and modernity are alive and well can be seen in the justice system, in science, in

political rights movements, in the very idea of universities; and so on.

To some

critics, there seems, indeed, to be a glaring contradiction in maintaining the death of

objectivity and privileged position on one hand, while the scientific community continues

a project of unprecedented scope to unify various scientific disciplines into a theory

of everything, on the other. Hostility toward hierarchies of value

and objectivity becomes similarly problematic when postmodernity itself attempts to

analyse such hierarchies with, apparently, some measure of objectivity and make

categorical statements concerning them.

Such critics

see postmodernism as, essentially, a kind of semantic gamesmanship, more sophistry than

substance. Postmodernism's proponents are often criticised for a tendency to indulge in

exhausting, verbose stretches of rhetorical gymnastics, which critics feel sound important

but are ultimately meaningless. (Some postmodernists may argue that this is precisely the

point.) In the Sokal

Affair, Alan

Sokal, a physicist, wrote a deliberately nonsensical article purportedly about

interpreting physics and mathematics in terms of postmodern theory, which was nevertheless

published by the Left-leaning Social Text, a journal which he and most of the scientific

community considered as postmodernist. Notable among Sokal's false arguments published in

Social Text was that the value of p changed over time and that the strength of Earth's gravity was

relative to the observer. Sokal claimed this highlighted the postmodern tendency to value

rhetoric and verbal gamesmanship over serious meaning. Sokal also co-wrote Fashionable

Nonsense, which criticizes the inaccurate use of scientific terminology in intellectual

writing and finishes with a critique of some forms of postmodernism. Ironically, postmodern

literature often self-consciously plays on the format and structure of

scientific writing, emphasizing the distinction between the complex content of the world

and its understanding in written form. To borrow a phrase from René Magritte,

some postmodern literature and art says "This is not a pipe", pointing out that the form

of technical writing is not necessarily connected to its content. The Sokal affair

also generated political controversy, with conservative pundits parading it as proof of

the irrelevance of the academic left, while leftists criticized Sokal of serving a

conservative agenda. Sokal, meanwhile, identified himself as an "unabashed Old

Leftist."

Some critics

feel that postmodernism is so strongly linked to politics that it does not qualify as a

philosophy. These critics claim that, inasmuch as many postmodernist arguments rely on

charges of racism and ethnocentrism

in traditional Western science, it is little more than an out. (excerpt

from <http: Postmodernism

- Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia>

Another

excellent resource page for Postmodernism: <http:// Postmodern Thought

>)