|

Disc 10

| |

MODERNISM

|

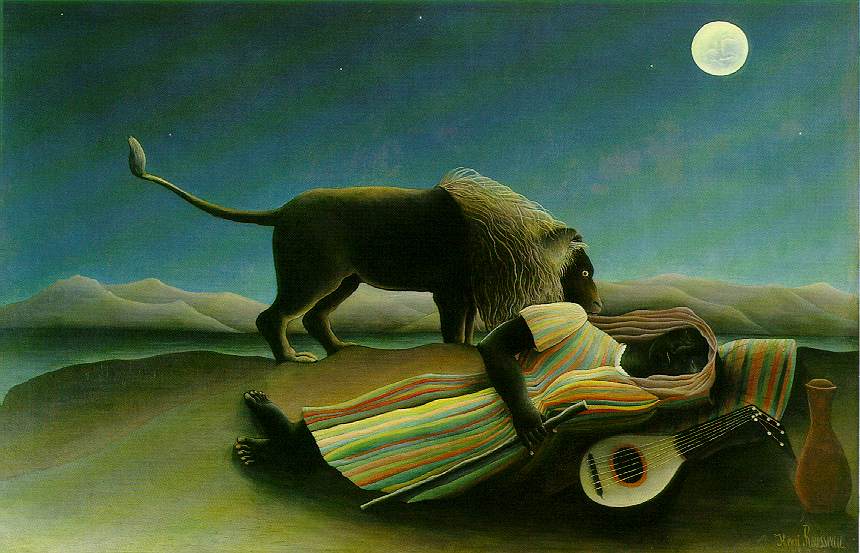

Henri Rousseau

The Sleeping Gypsy |

MODERNISM

IN LITERATURE

Modernism has no precise boundaries.

Like Romanticism, Realism, etc. the term is useful at a certain level, but frays into

complexities when periods, artists, styles and purposes are examined more closely. At its

strictest, in Anglo-American literature, the period runs from 1890 to 1920 and includes

Joyce, Pound, Eliot and Wyndham Lewis. But few of these writers shared common aims, and

the term was applied retrospectively. The themes of Modernism began well back in the

nineteenth century, and many did not reach fruition until the latter half of the twentieth

century, so that Modernism is perhaps better regarded as part of a broad plexus of

concerns which are variably represented in a hundred and twenty years of European writing

— experimentation, anti-realism, individualism, and intellectualism.

Why use Modernism at all? Because

writing in the period, especially that venerated by academia and by literary critics,

seems particularly challenging, which no doubt makes it suitable for undergraduate study.

Many serious writers come from academia, moreover, and set sail by Modernism's charts, so

that the assumptions need to be understood to appreciate the work. And quite different

from these is the growing suspicion that contemporary writing has lost its way, so that we

may see where alternatives lie if we understand Modernism better.

To varying extents, writing of the

Modernist period exhibits these features:

Experimentation

| Belief that previous writing was

stereotyped and inadequate. |

| Ceaseless technical innovation,

sometimes for its own sake. |

| Originality: deviation from the norm,

or from usual reader expectations. |

| Ruthless rejection of the past, even

iconoclasm. |

Anti-Realism

| Sacralisation of art, which must

represent itself, not something beyond. |

| Preference for allusion (often

private) rather than description. |

| World seen through the artist's inner

feelings and mental states. |

| Themes and vantage points chosen to

question the conventional view. |

| Use of myth and unconscious forces

rather than motivations of conventional plot. |

Individualism

| Promotion of the artist's viewpoint,

at the expense of the communal. |

| Cultivation of an individual

consciousness, which alone is the final arbiter. |

| Estrangement from religion, nature,

science, economy or social mechanisms. |

| Maintenance of a wary intellectual

independence. |

| Belief that artists and not society

should judge the arts, leading to extreme self-consciousness. |

| Search for the primary image, devoid

of comment: stream of consciousness. |

| Exclusiveness, an aristocracy of the

avant-garde. |

Intellectualism.

| Writing more cerebral than emotional.

|

| Tentative work, analytical and

fragmentary, more posing questions more than answering them. |

| Cool observation: viewpoints and

characters detached and depersonalised. |

| Open-ended work, not finished, nor

aiming at formal perfection. |

| Involuted: the subject is often act

of writing itself and not the ostensible referent. |

(excerpt from <http:

a critical introduction to

modernism in literature >

|

BACKGROUND

James Joyce was born on February 2,

1882, in Dublin, Ireland, into a Catholic middle-class

family that would soon become poverty-stricken. Joyce went to Jesuit schools, followed by

University College, Dublin, where he began publishing essays. After graduating in 1902, Joyce went to Paris with the intention of attending

medical school. Soon afterward, however, he abandoned medical studies and devoted all of

his time to writing poetry, stories, and theories of aesthetics. Joyce returned to Dublin

the following year when his mother died. He stayed in Dublin for another year, during

which time he met his future wife, Nora Barnacle. At this time, Joyce also began work on

an autobiographical novel called Stephen Hero. Joyce

eventually gave up on Stephen Hero, but reworked much

of the material into A Portrait of the Artist as a Young

Man, which features the same autobiographical protagonist, Stephen Dedalus, and

tells the story of Joyce’s youth up to his 1902

departure for Paris.

Nora and Joyce left Dublin again in 1904, this time for good. They spent most of the next eleven

years living in Rome and Trieste, Italy, where Joyce taught English and he and Nora had

two children, Giorgio and Lucia. In 1907 Joyce’s

first book of poems, Chamber Music, was published in

London. He published his book of short stories, Dubliners,

in 1914, the same year he published A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man in serial

installments in the London journal The Egoist.

Joyce began writing Ulysses in 1914, and when

World War I broke out he moved his family to Zurich, Switzerland, where he continued work

on the novel. In Zurich, Joyce’s fortunes finally improved as his talent attracted

several wealthy patrons, including Harriet Shaw Weaver. Portrait

was published in book form in 1916, and Joyce’s play,

Exiles, in 1918. Also

in 1918, the first episodes of Ulysses were published in serial form in The Little Review. In 1919,

the Joyces moved to Paris, where Ulysses was

published in book form in 1922. In 1923, with his eyesight quickly diminishing, Joyce began working

on what became Finnegans Wake, published in 1939. Joyce died in 1941.

Joyce first conceived of Ulysses as a short story to be included in Dubliners, but decided instead to publish it as a long

novel, situated as a sort of sequel to A Portrait of the

Artist as a Young Man. Ulysses picks up

Stephen Dedalus’s life more than a year after where Portrait

leaves off. The novel introduces two new main characters, Leopold and Molly Bloom, and

takes place on a single day, June 16, 1904, in Dublin.

Ulysses

strives to achieve a kind of realism unlike that of any novel before it by rendering the

thoughts and actions of its main characters— both trivial and significant—in a

scattered and fragmented form similar to the way thoughts, perceptions, and memories

actually appear in our minds. In Dubliners, Joyce had

tried to give his stories a heightened sense of realism by incorporating real people and

places into them, and he pursues the same strategy on a massive scale in Ulysses. At the same time that Ulysses presents itself as a realistic novel, it also works

on a mythic level, by way of a series of parallels with Homer’s Odyssey. Stephen, Bloom, and Molly correspond respectively

to Telemachus, Ulysses, and Penelope, and each of the eighteen episodes of the novel

corresponds to an adventure from the Odyssey.

Ulysses

has become particularly famous for Joyce’s stylistic innovations. In Portrait, Joyce first attempted the technique of interior

monologue, or stream-of-consciousness. He also experimented with shifting style—the

narrative voice of Portrait changes stylistically as

Stephen matures. In Ulysses, Joyce uses interior

monologue extensively, and instead of employing one narrative voice, Joyce radically

shifts narrative style with each new episode of the novel.

Joyce’s early work reveals the

stylistic influence of Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen. Joyce began reading Ibsen as a

young man; his first publication was an article about a play of Ibsen’s, which earned

him a letter of appreciation from Ibsen himself. Ibsen’s plays provided the young

Joyce with a model of the realistic depiction of individuals stifled by conventional moral

values. Joyce imitated Ibsen’s naturalistic brand of realism in Dubliners, A Portrait of the

Artist as a Young Man, and especially in his play Exiles.

Ulysses maintains Joyce’s concern with realism

but also introduces stylistic innovations similar to those of his Mo-dernist

contemporaries. Ulysses’s multivoiced narration,

textual self-consciousness, mythic framework, and thematic focus on life in a modern

metropolis situate it close to other main texts of the Modernist movement, such as T. S.

Eliot’s mythic poem The Waste Land (also

published in 1922) or Virginia Woolf’s

stream-of-consciousness novel, Mrs. Dalloway (1925).

Though never working in collaboration,

Joyce maintained correspondences with other Modernist writers, including Samuel Beckett,

and Ezra Pound, who helped find him a patron and an income. Joyce’s final work, Finnegans Wake, is often seen as bridging the gap between

Modernism and postmodernism. A novel only in the loosest sense, Finnegans Wake looks forward to postmodern texts in its

playful celebration (rather than lamentation) of the fragmentation of experience and the

decentered nature of identity, as well as its attention to the nontransparent qualities of

language.

Like Eliot and many other Modernist

writers, Joyce wrote in self-imposed exile in cosmopolitan Europe. In spite of this fact,

all of his work is strongly tied to Irish political and cultural history, and Ulysses must also be seen in an Irish context. Joyce’s

novel was written during the years of the Irish bid for independence from Britain. After a

bloody civil war, the Irish Free State was officially formed—during the same year

that Ulysses was published. Even in 1904, Ireland had experienced the failure of several home rule

bills that would have granted the island a measure of political independence within Great

Britain. The failure of these bills is linked to the downfall of the Irish member of

Parliament, Charles Stewart Parnell, who was once referred to as “Ireland’s

Uncrowned King,” and was publicly persecuted by the Irish church and people in 1889 for conducting a long-term affair with a married woman,

Kitty O’Shea. Joyce saw this persecution as an hypocritical betrayal by the Irish

that ruined Ireland’s chances for a peaceful independence.

Accordingly, Ulysses

depicts the Irish citizens of 1904, especially Stephen

Dedalus, as involved in tangled conceptions of their own Irishness, and complex

relationships with various authorities and institutions specific to their time and place:

the British empire, Irish nationalism, the Roman Catholic church, and the Irish Literary

Revival. |

Ulysses

Plot Overview

Stephen Dedalus spends the early morning hours of June 16, 1904, remaining aloof from his mocking friend, Buck

Mulligan, and Buck’s English acquaintance, Haines.

As Stephen

leaves for work, Buck orders him to leave the house key and meet them at the pub at 12:30. Stephen resents Buck.

Around 10:00 A.M., Stephen teaches a

history lesson to his class at Garrett

Deasy’s boys’ school. After class, Stephen meets with Deasy to

receive his wages. The narrow-minded and prejudiced Deasy lectures Stephen on life.

Stephen agrees to take Deasy’s editorial letter about cattle disease to acquaintances

at the newspaper.

Stephen spends the remainder of his morning

walking alone on Sandymount Strand, thinking critically about his younger self and about

perception. He composes a poem in his head and writes it down on a scrap torn from

Deasy’s letter.

At 8:00 A.M. the same morning, Leopold

Bloom fixes breakfast and brings his wife her mail and breakfast in bed. One of

her letters is from Molly’s

concert tour manager, Blazes Boylan (Bloom suspects he is also Molly’s

lover)—Boylan will visit at 4:00 this afternoon. Bloom returns downstairs, reads a letter from

their daughter, Milly,

then goes to the outhouse.

At 10:00 A.M., Bloom picks up an

amorous letter from the post office—he is corresponding with a woman named Martha

Clifford under the pseudonym Henry Flower. He reads the tepid letter, ducks

briefly into a church, then orders Molly’s lotion from the pharmacist. He runs into

Bantam Lyons, who mistakenly gets the impression that Bloom is giving him a tip on the

horse Throwaway in the afternoon’s Gold Cup race.

Around 11:00 A.M., Bloom rides with Simon

Dedalus (Stephen’s father), Martin

Cunningham, and Jack

Power to the funeral of Paddy Dignam. The men treat Bloom as somewhat of an

outsider. At the funeral, Bloom thinks about the deaths of his son and his father.

At noon, we find Bloom at the offices of

the Freeman newspaper, negotiating an advertisement

for Keyes, a liquor merchant. Several idle men, including editor Myles Crawford, are

hanging around in the office, discussing political speeches. Bloom leaves to secure the

ad. Stephen arrives at the newspaper with Deasy’s letter. Stephen and the other men

leave for the pub just as Bloom is returning. Bloom’s ad negotiation is rejected by

Crawford on his way out.

At 1:00 P.M., Bloom runs into Josie

Breen, an old flame, and they discuss Mina

Purefoy, who is in labor at the maternity hospital. Bloom stops in Burton’s

restaurant, but he decides to move on to Davy Byrne’s for a light lunch. Bloom

reminisces about an intimate afternoon with Molly on Howth. Bloom leaves and is walking

toward the National Library when he spots Boylan on the street and ducks into the National

Museum.

At 2:00 P.M., Stephen is informally

presenting his “Hamlet theory” in the National Library to the poet A.E. and the

librarians John

Eglinton, Best, and Lyster. A.E. is dismissive of Stephen’s theory and

leaves. Buck enters and jokingly scolds Stephen for failing to meet him and Haines at the

pub. On the way out, Buck and Stephen pass Bloom, who has come to obtain a copy of

Keyes’ ad.

At 4:00 P.M., Simon Dedalus, Ben

Dollard, Lenehan,

and Blazes Boylan converge at the Ormond Hotel bar. Bloom notices Boylan’s car

outside and decides to watch him. Boylan soon leaves for his appointment with Molly, and

Bloom sits morosely in the Ormond restaurant—he is briefly mollified by

Dedalus’s and Dollard’s singing. Bloom writes back to Martha, then leaves to

post the letter.

At 5:00 P.M., Bloom arrives at Barney

Kiernan’s pub to meet Martin Cunningham about the Dignam family finances, but

Cunningham has not yet arrived. The

citizen, a belligerent Irish nationalist, becomes increasingly drunk and begins

attacking Bloom’s Jewishness. Bloom stands up to the citizen, speaking in favor of

peace and love over xenophobic violence. Bloom and the citizen have an altercation on the

street before Cunningham’s carriage carries Bloom away.

Bloom relaxes on Sandymount Strand around

sunset, after his visit to Mrs.

Dignam’s house nearby. A young woman, Gerty

MacDowell, notices Bloom watching her from across the beach. Gerty subtly

reveals more and more of her legs while Bloom surreptitiously masturbates. Gerty leaves,

and Bloom dozes.

At 10:00 P.M., Bloom wanders to the

maternity hospital to check on Mina Purefoy. Also at the hospital are Stephen and several

of his medi-c-al student friends, drinking and talking boisterously about subjects related

to birth. Bloom agrees to join them, though he privately disapproves of their revelry in

light of Mrs. Purefoy’s struggles upstairs. Buck arrives, and the men proceed to

Burke’s pub. At closing time, Stephen convinces his friend Lynch

to go to the brothel section of town and Bloom follows, feeling protective.

Bloom finally locates Stephen and Lynch at Bella

Cohen’s brothel. Stephen is drunk and imagines that he sees the ghost of

his mother—full of rage, he shatters a lamp with his walking stick. Bloom runs after

Stephen and finds him in an argument with a British soldier who knocks him out.

Bloom revives Stephen and takes him for

coffee at a cabman’s shelter to sober up. Bloom invites Stephen back to his house.

Well after midnight, Stephen and Bloom

arrive back at Bloom’s house. They drink cocoa and talk about their respective

backgrounds. Bloom asks Stephen to stay the night. Stephen politely refuses. Bloom sees

him out and comes back in to find evidence of Boylan’s visit. Still, Bloom is at

peace with the world and he climbs into bed, tells Molly of his day and requests breakfast

in bed.

After Bloom falls asleep, Molly remains

awake, surprised by Bloom’s request for breakfast in bed. Her mind wanders to her

childhood in Gibraltar, her afternoon of sex with Boylan, her singing career, Stephen

Dedalus. Her thoughts of Bloom vary wildly over the course of the monologue, but it ends

with a reminiscence of their intimate moment at Howth and a positive affirmation. (excerpt

from Sparknotes.com)

Please read lines 1-200 of the text at

<http:// Telemachus (Ulysses ch1)> |

|

Frieda Kahlo

Diego and I |

| BACKGROUND

Virginia Woolf was

born on January 25, 1882, a descendant of one of

Victorian England’s most prestigious literary families. Her father, Sir Leslie

Stephen, was the editor of the Dictionary of National Biography

and was married to the daughter of the writer William Thackeray. Woolf grew up among the

most important and influential British intellectuals of her time, and received free rein

to explore her father’s library. Her personal connections and abundant talent soon

opened doors for her. Woolf wrote that she found herself in “a position where it was

easier on the whole to be eminent than obscure.” Almost from the beginning, her life

was a precarious balance of extraordinary success and mental instability.

As a young woman, Woolf wrote for the

prestigious Times Literary Supplement, and as an adult she

quickly found herself at the center of England’s most important literary community.

Known as the “Bloomsbury Group” after the section of London in which its members

lived, this group of writers, artists, and philosophers emphasized nonconformity,

aesthetic pleasure, and intellectual freedom, and included such luminaries as the painter

Lytton Strachey, the novelist E. M. Forster, the composer Benjamin Britten, and the

economist John Maynard Keynes. Working among such an inspirational group of peers and

possessing an incredible talent in her own right, Woolf published her most famous novels

by the mid-1920s, including The

Voyage Out, Mrs. Dalloway, Orlando,

and To the Lighthouse. With these works she reached the

pinnacle of her profession.

Woolf’s life was equally dominated by

mental illness. Her parents died when she was young—her mother in 1895 and her father in 1904—and

she was prone to intense, terrible headaches and emotional breakdowns. After her

father’s death, she attempted suicide, throwing herself out a window. Though she

married Leonard Woolf in 1912 and loved him deeply, she

was not entirely satisfied romantically or sexually. For years she sustained an intimate

relationship with the novelist Vita Sackville-West. Late in life, Woolf became terrified

by the idea that another nervous breakdown was close at hand, one from which she would not

recover. On March 28, 1941, she wrote her husband a note

stating that she did not wish to spoil his life by going mad. She then drowned herself in

the River Ouse.

Woolf’s writing bears the mark of her

literary pedigree as well as her struggle to find meaning in her own unsteady existence.

Written in a poised, understated, and elegant style, her work examines the structures of

human life, from the nature of relationships to the experience of time. Yet her writing

also addresses issues relevant to her era and literary circle. Throughout her work she

celebrates and analyzes the Bloomsbury values of aestheticism, feminism, and independence.

Moreover, her stream-of-consciousness style was influenced by, and responded to, the work

of the French thinker Henri Bergson and the novelists Marcel Proust and James Joyce.

This style allows the subjective mental

processes of Woolf’s characters to determine the objective content of her narrative.

In To the Lighthouse (1927),

one of her most experimental works, the passage of time, for example, is modulated by the

consciousness of the characters rather than by the clock. The events of a single afternoon

constitute over half the book, while the events of the following ten years are compressed

into a few dozen pages. Many readers of To the Lighthouse,

especially those who are not versed in the traditions of modernist fiction, find the novel

strange and difficult. Its language is dense and the structure amorphous. Compared with

the plot-driven Victorian novels that came before it, To the

Lighthouse seems to have little in the way of action. Indeed, almost all of the

events take place in the characters’ minds.

Although To the

Lighthouse is a radical departure from the nineteenth-century novel, it is, like

its more traditional counterparts, intimately interested in developing characters and

advancing both plot and themes. Woolf’s experimentation has much to do with the time

in which she lived: the turn of the century was marked by bold scientific developments.

Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution undermined an unquestioned faith in God that

was, until that point, nearly universal, while the rise of psychoanalysis, a movement led

by Sigmund Freud, introduced the idea of an unconscious mind. Such innovation in ways of

scientific thinking had great influence on the styles and concerns of contemporary artists

and writers like those in the Bloomsbury Group. To the Lighthouse

exemplifies Woolf’s style and many of her concerns as a novelist. With its characters

based on her own parents and siblings, it is certainly her most autobiographical fictional

statement, and in the characters of Mr. Ramsay, Mrs. Ramsay, and Lily Briscoe, Woolf

offers some of her most penetrating explorations of the workings of the human

consciousness as it perceives and analyzes, feels and interacts. (sparknotes.com) |

|

Edouard Manet -- Bar

at the Folies-Bergeres |

T.S. Eliot

Background

Thomas Stearns

Eliot, or T.S. Eliot as he is better known, was born in 1888 in St. Louis. He was the son

of a prominent industrialist who came from a well- connected Boston family. Eliot always

felt the loss of his family's New England roots and seemed to be somewhat ashamed of his

father's business success; throughout his life he continually sought to return to the

epicenter of Anglo- Saxon culture, first by attending Harvard and then by emigrating to

England, where he lived from 1914 until his death. Eliot began graduate study in

philosophy at Harvard and completed his dissertation, although the outbreak of World War I

prevented him from taking his examinations and receiving the degree. By that time, though,

Eliot had already written "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock," and the War,

which kept him in England, led him to decide to pursue poetry full-time.

Eliot met Ezra Pound in 1914, as well, and it

was Pound who was his main mentor and editor and who got his poems published and noticed.

During a 1921 break from his job as a bank clerk (to recover from a mental breakdown),

Eliot finished the work that was to secure him fame, “The

Waste Land”. This poem, heavily edited by Pound and perhaps also by Eliot's

wife, Vivien, addressed the fragmentation and alienation characteristic of modern culture,

making use of these fragments to create a new kind of poetry.

Eliot attributed a

great deal of his early style to the French Symbolists--Rimbaud, Baudelaire, Mallarme, and

Laforgue--whom he first encountered in college, in a book by Arthur Symons called The Symbolist Movement in Literature. It is easy to

understand why a young aspiring poet would want to imitate these glamorous bohemian

figures, but their ultimate effect on his poetry is perhaps less profound than he claimed.

While he took from them their ability to infuse poetry with high intellectualism while

maintaining a sensuousness of language, Eliot also developed a great deal that was new and

original. "The Love Song of J. Alfred

Prufrock" and “The Waste Land”, draw

on a wide range of cultural reference to depict a modern world that is in ruins yet

somehow beautiful and deeply meaningful. Eliot uses techniques like pastiche and

juxtaposition to make his points without having to argue them explicitly. As Ezra Pound

once famously said, Eliot truly did "modernize himself." In addition to

showcasing a variety of poetic innovations, Eliot's early poetry also develops a series of

characters who fit the type of the modern man as described by Fitzgerald, Faulkner, and

others of Eliot's contemporaries. The title character of "Prufrock" is a perfect

example: solitary, neurasthenic, overly intellectual, and utterly incapable of expressing

himself to the outside world.

As Eliot grew

older, and particularly after he converted to Christianity, his poetry changed. The later

poems emphasize depth of analysis over breadth of allusion; they simultaneously become

more hopeful in tone: Thus, a work such as Four Quartets

explores more philosophical territory and offers propositions instead of nihilism. The

experiences of living in England during World War II inform the Quartets, which address issues of time, experience,

mortality, and art. Rather than lamenting the ruin of modern culture and seeking

redemption in the cultural past, as The Waste Land

does, the quartets offer ways around human limits through art and spirituality. The

pastiche of the earlier works is replaced by philosophy and logic, and the formal

experiments of his early years are put aside in favor of a new language consciousness,

which emphasizes the sounds and other physical properties of words to create musical,

dramatic, and other subtle effects.

However, while

Eliot's poetry underwent significance transformations over the course of his career, his

poems also bear many unifying aspects: all of Eliot's poetry is marked by a conscious

desire to bring together the intellectual, the aesthetic, and the emotional in a way that

both honors the past and acknowledges the present. Eliot is always conscious of his own

efforts, and he frequently comments on his poetic endeavors in the poems themselves. This

humility, which often comes across as melancholy, makes Eliot's some of the most personal,

as well as the most intellectually satisfying, poetry in the English language. (Adapted

from Sparknotes.com) |

from "The

Waste Land"

I. THE BURIAL OF THE DEAD

APRIL is the cruellest month, breeding |

|

| Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing |

|

| Memory and desire, stirring |

|

| Dull roots with spring rain. |

|

| Winter kept us warm, covering |

5 |

| Earth in forgetful snow, feeding |

|

| A little life with dried tubers. |

|

| Summer surprised us, coming over the Starnbergersee |

|

| With a shower of rain; we stopped in the colonnade, |

|

| And went on in sunlight, into the Hofgarten, |

10 |

| And drank coffee, and talked for an hour. |

|

| Bin gar keine Russin, stamm' aus Litauen, echt deutsch. |

|

| And when we were children, staying at the archduke's, |

|

| My cousin's, he took me out on a sled, |

|

| And I was frightened. He said, Marie, |

15 |

| Marie, hold on tight. And down we went. |

|

| In the mountains, there you feel free. |

|

| I read, much of the night, and go south in the winter. |

|

|

| What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow |

|

| Out of this stony rubbish? Son of man, |

20 |

| You cannot say, or guess, for you know only |

|

| A heap of broken images, where the sun beats, |

|

| And the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief, |

|

| And the dry stone no sound of water. Only |

|

| There is shadow under this red rock, |

25 |

| (Come in under the shadow of this red rock), |

|

| And I will show you something different from either |

|

| Your shadow at morning striding behind you |

|

| Or your shadow at evening rising to meet you; |

|

| I will show you fear in a handful of dust. |

30 |

| Frisch

weht der Wind |

|

| Der

Heimat zu. |

|

| Mein

Irisch Kind, |

|

| Wo

weilest du? |

|

| 'You gave me hyacinths first a year ago; |

35 |

| 'They called me the hyacinth girl.' |

|

| —Yet when we came back, late, from the Hyacinth garden, |

|

| Your arms full, and your hair wet, I could not |

|

| Speak, and my eyes failed, I was neither |

|

| Living nor dead, and I knew nothing, |

40 |

| Looking into the heart of light, the silence. |

|

| Od' und leer das Meer. |

|

|

| Madame Sosostris, famous clairvoyante, |

|

| Had a bad cold, nevertheless |

|

| Is known to be the wisest woman in Europe, |

45 |

| With a wicked pack of cards. Here, said she, |

|

| Is your card, the drowned Phoenician Sailor, |

|

| (Those are pearls that were his eyes. Look!) |

|

| Here is Belladonna, the Lady of the Rocks, |

|

| The lady of situations. |

50 |

| Here is the man with three staves, and here the Wheel, |

|

| And here is the one-eyed merchant, and this card, |

|

| Which is blank, is something he carries on his back, |

|

| Which I am forbidden to see. I do not find |

|

| The Hanged Man. Fear death by water. |

55 |

| I see crowds of people, walking round in a ring. |

|

| Thank you. If you see dear Mrs. Equitone, |

|

| Tell her I bring the horoscope myself: |

|

| One must be so careful these days. |

|

|

| Unreal City, |

60 |

| Under the brown fog of a winter dawn, |

|

| A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many, |

|

| I had not thought death had undone so many. |

|

| Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled, |

|

| And each man fixed his eyes before his feet. |

65 |

| Flowed up the hill and down King William Street, |

|

| To where Saint Mary Woolnoth kept the hours |

|

| With a dead sound on the final stroke of nine. |

|

| There I saw one I knew, and stopped him, crying 'Stetson! |

|

| 'You who were with me in the ships at Mylae! |

70 |

| 'That corpse you planted last year in your garden, |

|

| 'Has it begun to sprout? Will it bloom this year? |

|

| 'Or has the sudden frost disturbed its bed? |

|

| 'Oh keep the Dog far hence, that's friend to men, |

|

| 'Or with his nails he'll dig it up again! |

75 |

| 'You! hypocrite lecteur!—mon semblable,—mon frère!' ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

- Line 20 Cf. Ezekiel 2:7.

- 23. Cf. Ecclesiastes 12:5.

- 31. V. Tristan und Isolde, i,

verses 5–8.

- 42. Id. iii, verse 24.

- 46. I am not familiar with the exact

constitution of the Tarot pack of cards, from which I have obviously departed to suit my

own convenience. The Hanged Man, a member of the traditional pack, fits my purpose in two

ways: because he is associated in my mind with the Hanged God of Frazer, and because I

associate him with the hooded figure in the passage of the disciples to Emmaus in Part V.

The Phoenician Sailor and the Merchant appear later; also the 'crowds of people', and

Death by Water is executed in Part IV. The Man with Three Staves (an authentic member of

the Tarot pack) I associate, quite arbitrarily, with the Fisher King himself.

- 60. Cf. Baudelaire:

- Fourmillante cité, cité pleine de rêves,

- Où le spectre en plein jour raccroche le passant.

- 63. Cf. Inferno, iii.

55–7:

- si

lunga tratta

- di gente, ch'io non avrei mai creduto

- che morte tanta n'avesse disfatta.

- 64. Cf. Inferno, iv.

25–27:

- Quivi, secondo che per ascoltare,

- non avea pianto, ma' che di sospiri,

- che l'aura eterna facevan tremare.

- 68. A phenomenon which I have often

noticed.

- 74. Cf. the Dirge in Webster's White

Devil.

- 76. V. Baudelaire, Preface to

Fleurs du Mal.

|

|

|