Policy

implications

Policy

implications

Policy

implications

Policy

implications

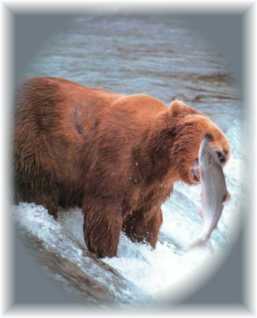

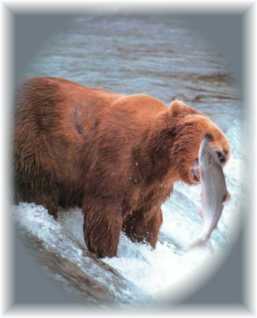

There are a number of immediate policy considerations that arise as a result of this analysis. First of all, there is the need to protect existing high quality grizzly bear habitat. This is clear from the scarcity of land areas that crest a value of 200 on our habitat quality scale (low 0-255 high). One also sees that as one moves inland, and away from the low (>150m elevation) estuaries and wetlands, grizzly habitat quality drops off noticeably when perusing the watershed suitability figures (see Grizzly Bear Habitat by Watershed Maps).

The implication here is one of contiguity of high quality habitat that is decidedly inland (and quite possibly greater than 150m of crow-flies distance to rich, riparian, wetlands—but is, in all other respects, potentially high quality habitat). The problem is that the farther bears must traverse to find these crucial riparian zones for intensive feeding sessions that occur twice a year (Spring and Autumn), the greater the likelihood that human activity will sever the usual transportation corridors with which the grizzlies would be most comfortable in using. If governments, environmentalists, and the scientific community wish to encourage the recovery of the grizzly species in habitat areas that are less than ideal, it is essential that planners take into account the need for sufficiently sized, situated, and contiguous transportation corridors be set aside and not developed.

It seems customary for each study to end with a plea for further research, and in this aspect, we follow closely the example set before us in the grizzly habitat and ecosystem literature. While our study has added its own small part to the methodological possibilities for exploring such topics, we clearly must acknowledge a number of limitations that we have encountered. For instance we are unable, at present, to establish firm quantitative data (nor qualitative for that matter) that reliably estimates how frequently grizzly bears actually “use” the areas that we have identified as “high quality”. This is an obvious shortcoming, but on that can be addressed to a certain extent by case study analysis and meta-analysis of existing research on grizzly bear movement patterns.

We are confident, however, that the

consensus in the literature regarding a observed grizzly habitat preference,

foraging practices, and so on, would hold for our results as well. Indeed,

our research shows similar patterns with the work done by the Round River

research group, and others. In the end, our results seem logically consistent

in a general way with the literature discussed above.