Blog Articles

Eyes Healed by Ayuverdic Treatment

Author: Ashok Puri | Posted: March 22, 2011Ayurvedic eye treatment helped Ashok Puri improve his eyesight after Western doctors declared his condition 'untreatable.'

Eyes Healed by Ayurvedic Treatment | by: Ashok Pi

Ashok Puri poses with the head doctor at the Sreedhareeyam eye clinic in Kerela, India.

Ayurvedic eye treatment helped heal my eyes, after Western doctors declared my condition 'untreatable'.

Some years ago, I had a cataract operation. At the time, I was overly anxious and excited to have my vision improved. Cataract operations are so routine and quick that I couldn't wait for the results. After the operation, I opened my right eye, expecting 20/20 vision.

Unfortunately, this was not the case. My sight went unchanged and remained at 20/60. I was diagnosed with idiopathic perifoveal telangiectasia shortly after. This is a rare, irreversible condition in which there is leakage of fluid from extra blood vessels around the fovea, a part of the eye that allows sharp vision for reading and watching television. The worst part was not just that this condition can lead to blindness, but that there is no known cure in the allopathic system of conventional medicine.

I was given one option, an expensive non FDA-approved injection called Avastin, which had no guaranteed results.

While I was still contemplating whether I should go for the injection or not, my job brought me to India. I went door-to-door looking for answers, exploring everything from homoeopathy, naturopathic doctors, eye specialists, to mystic men with healing powers and quacks with claims of magic cures. Finally, I ended up in an eye clinic in Kerala, southern India. The clinic, called Sreedhareeyam, practiced Ayurveda --a system ancient Indian medicine, developed over thousands of years of trial and error.

The head ayurvedic doctor assured me with confidence that the clinic could definitely arrest the leakage and further deterioration of my eye, but could not guarantee restoration of the already deleterious effects of the damage already done.

This news was very reassuring. After three weeks of intense treatment in the clinic, I returned to Vancouver. My total expenses, including lodging, fees, treatments, a four-month supply of medicine and all meals, was only $800 CAD. None of this, of course, was covered by the Medical Service Plan (MSP).

How did this ayurvedic treatment work? My typical day started daily at 5:30 am, with freshly prepared mixture of herbal extracts called kashayam. At 7 am, I was off to the massage centre where two strong masseurs were ready to tone me with specially prepared oil mixtures. They work on you in the such synchronized time that you would think only one person is massaging you. At around 9:30 am, I would begin the netra dhara, a special cleansing technique of pouring of herbal extracts in a stream over the eyes for 15 – 20 minutes.

After receiving treatment, Ashok Puri and his fellow patients enjoy their surroundings.

After lunch, I went through shirodhara, which involves gently pouring of liquids over the forehead -- the third eye, in Hindu religion. Of all the treatments, I loved the shirodhara the most, during which I felt completely stress-free.

I was also treated with khizi, a massage given through heat which essentially involves very hot oil being applied through a technique similar to the energetic strokes of a wire brush.

All the above treatments are essentially preparing the patient for the final treatment, which is performed for the last full week. Tharpanam means retention of medicines over the eyes for 30 minutes or more a day. Big wells of dough are put onto your eyes, and are poured on with warm herbalated ghee (clarified butter). The frequency and dosage depends on the extent of the problem. You are kept blind folded for almost three hours with the most refreshing bandage I have ever felt. Imagine petals of cooling flowers being used, instead of cotton.

Evenings are free time, so people gather in the front of the old home of the family to share their stories and experiences. Some sing hymns, Bollywood songs, and people from different regions tell a variety of jokes. Many people go to the evening congregation at the temple. It is a delightful sight to see all the walls of the temple lit with thousands of diyas (oil filled lamps). The place is filled with high energy. Everybody has a positive attitude and is in good spirits. Dejected people who had previous failed treatments feel once again full of hope after hearing the success stories of others.

Most of the medicines used in the clinic are prepared from the herbs grown on-site. Panchkarama, herbal massages, shirodhara, basti, netra dhara and tharpanam are the main treatments. The most common treatments are for near-sightedness, glaucoma, diabetic retinitis, retinitis pigmentosa, age-related degeneration and diseases related to the optic nerve.

When I came back, my ophthalmologist in Vancouver was surprised to find that there was no leakage and that my eye site had become 20/20 in both eyes. He taunted me as to why I was still wearing glasses. Since the appointment, I only wear glasses while reading.

The Sreedhareeyam eye clinic is operated by a team of highly trained and experienced ayurveds (doctors). The business has been running in the family for many generations. The premises is set up in a resort-like facility away from the hustle of big cities and located near a small village. It has a capacity for over 300 patients and escorts, and contains a gorgeous kitchen which prepares all fresh vegetarian meals, as well as a canteen with internet facilities. It has a large research and development department and modern factories where the clinic's medications are manufactured. About 10% of the patients are from abroad, 35% are from the city of Kerala, and the rest come from from all parts of India.

The dedication, sincerity of purpose, and a belief in the Hindu Goddess Badri Maa are quoted as the main reasons for the successful treatments of all the patients. Morning and evening prayers are performed daily by most patients and the doctors.

Ayurvedic ophthalmology, or Netra Chikitsa, is a well-documented branch of Ayurveda, the ancient holistic medical science. Numerous Ayurvedic documents cover treatments for 70 to 90 eye ailments. Ophthalmology is taught up to the post graduate level, which takes up to eight and a half years to complete.

Most eye-patients reach this treatment centre after exhausting all other options available to them. Presently, ayurvedic medicine is said to be the last hope for people who suffer from blindness. The specialists and doctors I have seen in Canada cannot believe that this ayurvedic treatment is working, nor can they explain to me why my condition is not worsening.

Richard Dawkins, a renowned British ethologist, once said "there is no alternative medicine, there is only medicine that works and medicine that doesn't work." It makes me wonder why the mainstream medical profession does not open its doors and gain some insight into the magic of these so-called alternatives, complementary systems. Most of these alternatives practitioners are finding it hard to compete with the mainstream system, as their treatment is not recognized by our government.

Regardless, I go to my clinic in India for annual checkups and treatments. I do not know what brings me back every year. It may be the faith in the doctors, the medicines or the Goddess.

Photos Courtesy of Ashok Puri.

Professor James Busumtwi-sam outlines key issues in global health with reference to the UN's Millennium Development Goals.

Diasporas and Global Health | by: James Busumtwi-Sam

Professor James Busumtwi-sam speaks at the Engaging Diasporas in Development dialogue "Poverty reduction and economic Growth" Photo: Greg Ehlers.

What is health? According to the 1946 WHO constitution it is "a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity." Today this definition is widely accepted, as is the notion that, in addition to its biomedical and technical elements, we should be concerned with the broader social determinants of health as shaped by the distribution of money, power and resources at global, national and local levels. This broadened understanding of and approach to health reflects increased awareness that health issues are affected by factors traditionally considered outside the health sector. Globalization and the proliferation of non-governmental actors and institutions (public and private) strongly influence the ability of national and local authorities to protect and promote public health, but profound health disparities exist across the globe. Situating health within the context of broader social determinants provides a better understanding of the sources of health inequities.

The absence of equity in the provision of health services is considered to be one of the major impediments to achieving positive health outcomes. The WHO's 1998 World Health Report Health for All in the 21st Century, linked good health to the advancement of human rights, greater equity, and gender equality among other things. Social determinant of health generate health inequalities. An emphasis on health equity implies that need -- not income/wealth, power and privilege -- should be the major determinant of health-care access and ultimately of health outcomes. This notion was embodied in the 1978 Alma Ata Declaration. However, the profound disparities in health opportunities and outcomes across the world today, indicate quite a divergence between recognizing a 'right to health' in principle and in practice.

There is a stark relationship between poverty and poor health -- in countries classified as 'least developed' or 'low income', life expectancy is just 49 years, and one in ten children do not reach their first birthday. In high-income countries, by contrast, the average life expectancy is 77 years and the infant mortality rate is six per 1000 live births. There appears to be a 'vicious cycle' in the relationship between poverty and ill health -- poverty contributes to ill-health and ill-health leads to poverty. A recent report by the WHO and World Bank Dying for Change: Poor People's Experience of Health and Ill-Health, notes that poverty creates ill-health because poor people tend to live in environments that make them sick, without decent shelter, clean water or adequate sanitation. It is within this context that the deprivations, exclusions and inequities associated with poverty and inequality have been highlighted as one of the biggest obstacles to promoting health globally.

The goal of achieving more equitable healthcare around the world faces serious challenges. As the WHO itself acknowledges, while there have been improvements in areas such as childhood immunization, there have been setbacks to providing equitable access to essential health care worldwide. Health system constraints including financial barriers and health worker shortages, combined with challenges such as the HIV epidemic, have hampered progress towards achieving health for all. In the 30 plus years since the Alma Ata Declaration, the equity and community-based (bottom-up) emphasis it espoused has been eroded in favour of 'efficiency' cost-utility (top-down) reforms based on neoliberal market economic principles (the so-called 'Washington Consensus' favouring privatization, deregulation, etc). User fees, cost recovery, private health insurance, and public–private partnership became the focus for healthcare service delivery. Overall, healthcare was seen in terms of economic benefits that improved health delivers (i.e., human capital for development), rather than as a consequence and fruit of development.

Aids warning sign as part of a USAID campaign with the Ghana police. Photo: Shaheen Nanji.

More recently, the major MFIs and bilateral donors have made some modifications to this model. Some analysts talk of a 'socially-inclusive' neoliberalism (the so-called 'post-Washington Consensus') emerging at the end of the 1990s and into the new millennium. The MFIs and bilateral donors made 'poverty reduction' a cornerstone of their lending programs, and created new lending programs to accommodate higher pro-poor public expenditure in the South. It was within the context of this new agenda that the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were adopted in 2000.

The United Nations Millennium Declaration signed in September 2000 led to the adoption of the MDGs -- a set of eight goals and a number of numerical targets to be achieved by 2015 or earlier. At the heart of the MDGs is the recognition that health is central to the global agenda of reducing poverty as well as an important measure of human well-being. Health is the explicit focus of three of the eight goals, and health issues are acknowledged as central to the attainment of other key goals including eradicating extreme poverty and hunger, gender equality, and environmental sustainability.

The global financial and economic crisis that began in 2008, however, has had a negative impact on progress towards achieving the MDGs. By the end of 2010 – just five years to the target year of 2015 – the World Bank was reporting lack of progress in several key MDG indicators in poorer countries including health, nutrition, and poverty-reduction indicators. Maternal mortality has shown the least progress of all the health-related MDGs, the annual decline in child mortality is insufficient, and the global shortage of health workers reached 4.3 million in 2006. Small developing countries are disproportionally affected by emigration of health workers and donor funding for reproductive health on a per woman basis has fallen by over 50 per cent in 42 of the 49 least developed countries since the mid-1990s.

The contributions members of the diaspora make to global health can be situated within the context of debates over health equity and the challenges to realizing the health-related MDGs. In 2008 the WHO placed renewed emphasis on primary health care in its report Primary Health Care: Now More than Ever. Achieving this goal will require reducing exclusion and social disparities in health, reorganization of health services around people's needs and expectations, integration of health into all other sectors, pursuing collaborative models of policy dialogue and increasing stakeholder participation. In addressing diaspora contributions to improving global health we might ask:

- In what ways can the diaspora help achieve these goals?

- What are the main areas in which the diaspora have a comparative advantage or unique opportunity to engage with communities in their places of origin/attachment to help in the 'development' process, and how can they organize to increase the impact they will have (conversely, what are the constraints they face)?

- What are the opportunities/insights for successive generations to participate in the development process in their places of origin/attachment?

- Do subsequent diasporic generations lose some of the socio-cultural context that might provide them greater or lesser insight into their places of origin/attachment? Is the perspective they bring significantly different and if so, how?

- How do diaspora bring about positive 'systemic' changes in their places of origin/attachment?

- How might the diaspora accelerate more substantive or fundamental changes than are associated with small, discrete projects such as improving sanitation and access to safe drinking water in a single village?

- What opportunities are there for diaspora to engage in advocacy work, knowledge creation, and capacity building? Are there any positive changes that diasporic researchers bring about through their studies and proposals?

- In what ways are these experiences and interchanges transforming health practices and understandings in the North? (i.e., what is the looping effect?)

James Busumtwi-Sam is Associate Professor of Political Science and (acting) Development & Sustainability program at Simon Fraser University.

Climate refugees: Diaspora response to a human health crisis

Author: Douglas Olthof | Posted: March 13, 2011Over the next 30 years, some 30-40 million Bangladeshis will be displaced due to climate change. Vancouver's Bangladeshi community advocates for an immediate global response.

Climate refugees: Diaspora response to a human health crisis | by: Douglas Olthof

Bangladeshi women try to adapt their livelihood strategies to a landscape changing rapidly due to climate change. Photo: Mohammad Zaman.

Over the next 30 years, some 30-40 million Bangladeshis will take what they can from their homes and move to higher ground. They will pour into Dhaka and other Bangladeshi cities, overflowing the already expansive slums and bastees; they will cross international borders into India, Myanmar and other countries looking for livelihoods, homes and some semblance of security for their families. This mass of humanity, at least equal in size to the entire population of Canada, will not be pulled to the cities by the promise of a better future. Theirs will not be an economic migration associated with new opportunities, but instead a forced exodus driven by an unprecedented environmental calamity that they have played virtually no part in causing. They will make up the largest group of climate refugees this world has ever seen.

Bangladesh is the world's most densely populated deltaic country. More than half of the country's 160 million inhabitants make their homes on a massive delta formed by the confluence of the Ganges, Brahmaputra and Meghna rivers. A one-meter rise in the sea level – as is predicted by some of the most conservative climate change models – would inundate roughly a third of Bangladesh's land and trigger a forced migration unprecedented in its scale.

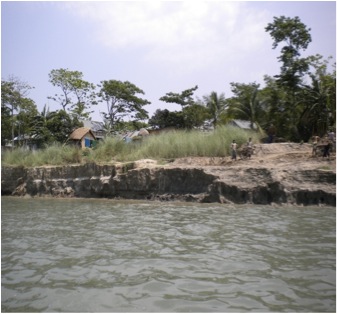

The Ganges (locally called Padma), one of the three major rivers, is eating away valuable agricultural lands every year, making thousands homeless and landless destitute. Photo: Mohammad Zaman

Vancouver is home to some 6000 Bangladeshis who are all too aware of the disaster facing their home country. Over the past 8-10 years the impending humanitarian crisis facing Bangladesh has grown from a topic of conversation to a focal point of organization within Vancouver's Bangladeshi community. In 2009 the Society for Bangladesh Climate Justice was formed as a unified effort to enhance awareness of climate change, promote the cause of Bangladesh internationally, support action research in the areas of climate change mitigation and adaptation, and to work with the Canadian government to help Bangladesh manage what is sure to be an overwhelming humanitarian catastrophe.

Dr. Mohammad Zaman is Executive Director of the Society for Bangladesh Climate Justice. He points out that the community of South Asian states (SAARC) has established mechanisms for sharing climate change data, but has done nothing to address the issue of climate refugees and migration. Indeed, the international community in general has yet to devise a framework for handling the estimated 200 million people around the world who will become permanent climate refugees by 2050. Such a framework will be necessary to manage the inevitable international migration of people displaced by flooding, drought, coastal erosion and other climate induced crises. According to Dr. Zaman, however, the solutions to these problems must also include strengthening the capacity of countries like Bangladesh to mitigate and adapt to them.

Climate refugees face a set of problems distinct from those affecting other migrant groups. Unlike those who uproot to the cities in search of economic opportunities, climate-induced migrants often lack preparation for the journeys they embark on. They leave their homes in a state of distress and may be unable or unprepared to establish new livelihoods. They experience ongoing trauma with lasting effects on their physical and mental health. In this context, Dr. Zaman points to the need for a holistic approach to health incorporating community building, livelihood development and trauma counseling – in addition to medicine and treatment for the physical body.

Riverbank erosion alone displaces over 100,000 people every year. People displaced are poor and need urgent support and assistance. Photo: Mohammad Zaman.

The crisis facing Bangladesh is not a potential consequence of climate change; it is catastrophe that is unfolding at this very moment. Already 100,000 Bangladeshis are displaced by climate-induced erosion along riverbanks and coastal areas every year. Nor is it a problem peculiar to Bangladesh. Upwards of 50 million Indians face the prospect of forced migration as rising sea levels subsume coastal areas in that country. Meanwhile, island nations like the Maldives could be completely submerged in mere decades.

For most people living in the high-consumption countries responsible for the vast majority of green house gas emissions, climate change represents an amorphous threat lurking somewhere in the uncertain future. For Dr. Mohammad Zaman and the Society for Bangladesh Climate Justice, climate change is an immediate and dire threat to the lives, livelihoods and health of their loved ones and countrymen. Their objective is to convince the public and the government of Canada that concrete actions must be taken not only out of compassion for Bangladeshis, but out of recognition that the scale of the humanitarian crisis facing Bangladesh and its neighbouring countries is of grave consequence to the entire world.

Dr. Mohammad Zaman is part of a distinguished panel of speakers participating in the Engaging Diasporas in Development project's "Improving Global Health" dialogue. Dr. Zaman will share experiences and insights from his work with the Society for Bangladesh Climate Justice and will highlight the environmental, economic and social determinants of health.

Panos Network provides a new lens for international development

Author: Douglas Olthof | Posted: March 13, 2011It's past time to reject the notion of an economically prosperous, technically advanced "North" and a technologically backward, politically naïve and ill-informed "South".

Panos Network provides a new lens for international development | by: James Busumtwi-Sam

Faced with complexity, it is often prudent to simplify. To that end, we have invented concepts like "left" and "right" as tools to better understand politics, and use broad categories like "middle class" or "below the poverty line" to build manageable categories out of unwieldy continuums. In some instances, these simplifications help us to make sense of the context in which our busy lives unfold. In other cases, they obscure important dimensions of reality, generate unrealistic perceptions of the world and throw up barriers to achieving a more equitable, just and sustainable global society. The portrayal of the world in terms of a "global north" and a "global south" is a case in point.

According to Jon Tinker, founder of the Panos Network and Executive Director of the Panos Institute of Canada, the concept of a global "north" and "south" is a relic of a bygone era. In the wake of the Second Word War, as communism spread and the powers of Western Europe and North America moved to check its expansion, it became useful to think in terms of a world divided between the First World West, the Second World East and the Third World South. After the fall of the Berlin Wall and the Warsaw Pact, the Second World was dropped and a simplistic two-part vision of the world remained.

Jon Tinker thinks it's high time this conceptual hand-me-down is tossed in the dustbin of history. He points out that the "North and South are no longer broadly distinct and homogeneous groups. Today, they are overlapping and heterogeneous categories, with at best only an historical validity " He argues that, while the "North/South lens" was sometimes useful to the social justice and development movements, ultimately "using [it] is not just lazy. It's dangerous. It hinders us from seeing, let alone addressing, today's unjust and socially unsustainable imbalances of power and wealth."

The Panos Institute of Canada is part of the global Panos Network consisting of eight independent institutes. The network's members in London, Paris, East Africa, Southern Africa, West Africa, South Asia, the Caribbean and Canada engage in programmes with a strong focus on economically and socially disadvantaged people around the World. The Panos Institute of Canada, of which Jon Tinker is Executive Director, makes HIV-AIDS its primary area of focus.

One of the most powerful methodologies they bring to bear on the immense problem of HIV-AIDS is the commonalities lens: an explicit rejection of the notion that there exists a "North" characterized by economic prosperity, technical ability and expertise and a "South" that is "poor, ill-informed, technologically backward, badly-trained and politically naive." Instead of fixating on differences between countries and cultures, the commonalities lens focuses on what we have in common. It "helps us realize what we share, and provides a basis for solidarity, and for learning from one another as equals."

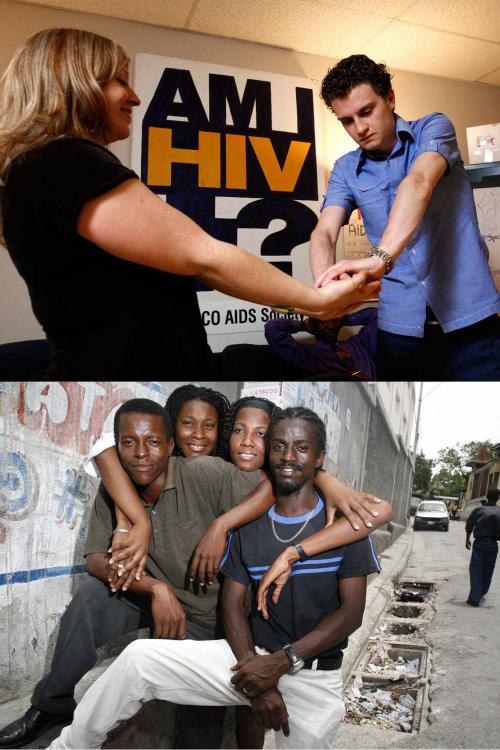

In 2007 the Panos Institute of Canada teamed up with public health specialist and photographer Pieter de Vos to produce AIDS in Two Cities: a photography project highlighting the common elements of HIV/AIDS issues in Port-au-Prince and Vancouver. Photos: Pieter de Vos - AIDS in Two Cities.

A recent initiative of Panos Canada illustrated vividly the power of the commonalities lens. In November 2008 the Panos Institute of Canada brought 10 Haitian AIDS experts to Vancouver. The Haitian delegation did not come to Canada to receive training; they were not invited to play the part of recipients; nor was the aim of the exchange to 'build their capacity.' The goal of the project was to provide an opportunity for the experts from Haiti to share their insights with their Canadian counterparts. In the context of the dominant development paradigm, this was a radical initiative.

The project evolved as a follow up to The Panos Institute of Canada's 2007 collaboration with public health specialist and photographer Pieter de Vos: AIDS in Two Cities. This captivating photo essay juxtaposed images from Port-au-Prince and Vancouver not as means of pointing out differences, but of highlighting commonalities. What emerged from AIDS in Two Cities is the understanding that the problems surrounding HIV/AIDS in Port-au-Prince and Vancouver are characterized by differences of degree, but commonalities of type. What emerged form the Haiti Exchange was that AIDS experts charged with addressing these problems in Port-au-Prince could teach a great deal to their counterparts in Vancouver.

Youth Speak to Youth: The AIDS in Two Cities portrays the common experiences of youth-driven theatrical groups working to educate their peers to the dangers of HIV/AIDS in Vancouver and Port-au-Prince. Photos: Pieter de Vos - AIDS in Two Cities.

The sad history of "development" in the latter half of the 20th century has exposed as folly the notion that having achieved advanced economic development is the only necessary and sufficient condition for knowing how others should do the same. We now understand and acknowledge that underdevelopment is not simply a result of 'insufficient local capacity'; reality is a much more complex picture. The "North/South lens" reinforces that discredited perspective. By recognizing the diversity that exists within countries and the commonalities that exist between them, the commonalities lens suggests how a more equitable exchange might be possible and how we might begin to redress the power asymmetries that have for 60 years rendered the "North/South" development relationship impotent.

A Vancouver doctor brings a cure for clubfoot to children in Uganda

Author: Douglas Olthof | Posted: March 8, 2011Ugandan paramedicals are trained by the Uganda Sustainable Clubfoot Care project to apply an economically and socially feasible treatment to a crippling birth defect.

A Vancouver doctor brings a cure for clubfoot to children in Uganda | by: Douglas Olthof

In 1998 Dr. Shafique Pirani returned to Uganda to visit his birthplace and childhood school. A member of the Ismaili diaspora, Dr. Pirani had been among those expelled from Uganda by Idi Amin's government in 1972. In making preparations to visit the country of his birth, he had not intended to tackle problems of Ugandan public health, but while on that visit he bore witness to a problem that he was uniquely qualified to diagnose and address.

Years before his fateful trip to Uganda, Dr. Priani had taken a research interest in a congenital musculoskeletal disorder known commonly as clubfoot. This disorder occurs in roughly 1 in 1000 children and, if untreated, leads to deformation of the feet. This can leave the sufferer walking on the sensitive dorsum (top) of the foot, resulting in chronic pain, immobility, ulcerations, infection and, often, stigmatization. At the time of Dr. Pirani's visit, the most commonly practiced treatment for clubfoot around the world was corrective surgery.

Surgical treatment for clubfoot in Uganda was not an option. In a country of 28 million with a birth rate of 3.5% annually, approximately 1500 Ugandan children are born with clubfoot every year. As late as 2008 the country had 20 practicing orthopedic surgeons, most of whom were concentrated in Kampala and focused on trauma. Dr. Pirani recognized a dire need for alternative treatments for clubfoot in Uganda that could be economically and socially feasible.

A Ugandan baby born with the potenitally crippling congeatal disorder know as "clubfoot." Photo: USCCP

In the late 1940s, a doctor at the University of Iowa named Ignacio Ponseti was investigating the long-term results of clubfoot surgeries. The results he observed were not encouraging and he soon began work on a nonsurgical method to correct the disorder. The resulting "Ponseti Method" proved far superior to surgical treatment, but failed to catch on with the medical community for another 50 years. In 1997 Dr. Pirani had begun using the Ponseti method in his Vancouver practice, with promising results. In Uganda, Dr. Pirani saw the life altering implications of the Ponseti Method for thousands of children.

Soon after his 1998 visit, Dr. Pirani began working on how the Ponseti Method could be brought to Uganda, bearing in mind the limited number of surgeons. The solution was to train paramedical health care professionals in the method, so that they would treat the children. Dr. Pirani developed training materials, and set about organizing Ponseti Method workshops and seminars for paramedicals in Uganda, sponsored by the Rotary Clubs of Burnaby and New Westminster Royal City. Dr. Pirani's pilot studies showed that children born with clubfeet could have the clubfeet corrected by paramedicals trained in the Ponseti Method.

Dr. Pirani was then successful in securing $1 million in funding from the Canadian International Development Agency for the Uganda Sustainable Clubfoot Care Project. Through partnerships with several organizations including Uganda's Makerere University and the Uganda Ministry of Health, the project has built capacity within the Ugandan healthcare system to screen for, diagnose and treat clubfoot using the Ponseti Method. Dr. Pirani and his partners have worked to adapt the Ponseti Method to make the treatment socially and economically feasible for Uganda. The estimated cost for treatment is less than $150 per child, with benefits potentially lasting an entire lifetime. The ultimate objectives are to develop treatment and training capacity in Uganda such that project's like the USCCP are no longer required.

Paramedicals in Uganda trained by the USCCP apply a locally-appropriate adaptation of the "Ponseti Method" to treat clubfoot. Photo: USCCP

Throughout its years of operation, the Ugandan Sustainable Clubfoot Care Project has encountered some challenges. For example, as with many development projects spanning international boundaries, the project initially struggled to develop a truly inclusive and participatory approach. On the whole, however, the project has been tremendously successful. The model pioneered by the Dr. Pirani and the USCCP has already been expanded to Malawi, Rwanda, Kenya, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, and Bangladesh. Health care practitioners and officials in Brazil, Honduras, India and Nepal are also drawing lessons from the UCSSP in Uganda. The project stands as a shining example of how members of the diaspora can build international connections that foster significant and sustainable improvements in health.

Dr. Pirani will share his experiences and insights at the Engaging Diasporas in Development project's "Improving Global Health" dialogue on March 16, 2011.

Bibliography:

Naddumba, E.K. (2009) "Preventing Neglected Club Feet in Uganda: A Challenge to the Health Workers with Limited Resources". In: East African Orthopedic Journal Vol. 3,

No. 1.

Pirani S, Naddumba E, Mathias R, Konde-Lule J, Penny JN, Beyeza T, Mbonye B, Amone J, Franceschi F. "Towards effective Ponseti clubfoot care: the Uganda Sustainable Clubfoot Care Project." Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2009 May; 467(5):1154-63.

Global health through the diaspora lens

Author: Douglas Olthof | Posted: March 7, 2011Regional maps depicting some of the places Vancouver diasporas identify with.

Global Health through Diaspora Lens | by: Douglas Olthof

What does health mean to you? The question might sound simple, but only until you try to answer it. Is health simply a matter of a disease-free mind and body, or are there social, cultural, spiritual or environmental dimensions to be considered? How does our cultural, social and community background influence our understanding of 'health'? These are just a few of the questions we will ponder when the "Engaging Diasporas in Development" project convenes its second public dialogue: Improving Global Health.

After completing a successful dialogue on poverty reduction and economic growth in January of this year, we at the Engaging Diasporas in Development project are steering the conversation in the direction of global health. Our goal is to address not only how diasporas living in the Vancouver area affect health in the countries and regions of the world with which they identify, but also how those same individuals draw upon their international connections and their appreciation of diverse paradigms to influence health and health care in Canada.

We will begin the dialogue with a framing discussion by asking the "what does health mean to you?" Here, we hope to access alternative conceptions of health that draw on various cultural, spiritual and intellectual traditions. We will then ask: "what are the unique qualities that diaspora bring to improving global health?" Our conversations thus far have led us to recognize a plurality of insights and abilities that inhere in members of the diaspora. Our hope is to focus specifically on how these insights and abilities can be brought to bear on issues of global health.

Following an open and inclusive discussion intended to "define" global health, the conversation will shift toward exploring specific examples of diaspora health initiatives. To this end, we have assembled a distinguished panel including professor of paediatric orthopedics Dr. Shafique Pirani, HIV/AIDS campaigner Steven Pi, neuroscience nurse and NGO founder Marj Ratel, international neurological healthcare organizer Derek Agyapong-Poku and climate activist Dr. Mohammed Zaman. The panel will describe the initiatives and their impacts, their unique contributions as diasporas and the potential for more active and effective diaspora involvement. This will be followed by an open discussion drawing in reactions, perspectives and experiences from dialogue participants.

The Engaging Diasporas in Development project has identified "translocality" as a key component of the diaspora experience. "Translocality" refers to simultaneously being and acting in multiple localities across and within national boundaries. The "Improving Global Health" dialogue will address translocality by asking how diasporas transcend boundaries to serve as a bridge between the 'Global North' and 'Global South.' Distinguished speakers will address this question with reference to their own experiences working in the area of health in various settings. They will also address the impacts trans-local interactions have on transforming health practices, systems and understanding here in Canada. This will be followed by an open discussion exploring existing diaspora efforts to address global health issues and the as yet unrealized potential for further engagement.

Engaging Diasporas in Development project Co-directors Joanna Ashworth (left) and Shaheen Nanji (right). Photo: Greg Ehlers.

The "Improving Global Health" dialogue is the second in a series of 5 dialogues organized by the Engaging Diasporas in Development Project.

In health,

Joanna Ashworth and Shaheen Nanji

Co-Directors

SFU's Engaging Diasporas in Development project

Vancouver's diaspora shares development stories

Author: Douglas Olthof | Posted: March 1, 2011On January 19, 2011, members of Vancouver's diaspora and development communities came together to exchange stories and ideas.

Vancouver's diasporas share development stories | by: Douglas Olthof

Dialogue story tellers gathered together before the Engaging Diasporas in Development dialogue. Photo: Greg Ehlers.

On January 19, 2011 the Engaging Diasporas in Development Project convened the first in its series of public dialogues. The dialogue was entitled "Innovations in Poverty Reduction and Economic Development" and covered three core themes: responding to basic needs through grassroots mobilizations, business and economic development, and tapping the potential: learning from the diaspora.

Participants began filtering into the Morris J. Work Cetre for Dialogue amid considerable buzz. Soon thereafter, as the sounds of dozens of conversations mingled above the assembly, a single voice cut through the din and invited everyone to join together in conversation and collaboration. Vanessa Richards urged the participants to join in song and for the next few minutes the diverse crowd became a united chorus. With melody and harmony still reverberating through the room, the dialogue had begun.

Vanessa Richards leads the group in an inspirational chorus. Photo: Greg Ehlers.

The first session got underway with a focus on "responding to basic needs through grassroots mobilization." Three 'storytellers' shared their experiences with the assembled participants. Kaye Kerlande, conveyed her experience as a second generation Canadian of Haitian decent and her struggle to formulate a meaningful response to the overwhelming disaster that befell that country in January of 2010. Sumana Wijeratna, a Sri Lankan-Canadian, was the second storyteller and her story can be found in one of previous blogs here. Finally, Lorie Corcuera of ENSPIRE shared her experiences in organizing with other members of the Filipino diaspora and partnering with an organization in that country to create long-term housing solutions for low income and marginalized families in Manila. What followed was an open dialogue covering topics including the role of women in development, the varied nature of diaspora identity and the importance of local partnerships, to name a few. SFU Communications professor June Francis tied the first session together by highlighting common themes and providing thoughtful insights on the empathy and visceral connection that diasporas bring to their development work.

The second section of the dialogue addressed "business as economic development." Two storytellers, Miriam Egwalu and Antonio Arreaga, constructed a compelling launch pad for the discussion. Miriam Egwalu is an immigrant to Canada from Uganda and her story can be found in one of our previous blog posts here. Antonio Arreaga is Honorary Consul of Costa Rica in Vancouver. He related to the dialogue participants a number of sector-specific examples whereby "Canadian know-how" was "tropicalized" to improve the performance of Central American businesses. The session continued with a wide-ranging dialogue covering topics including the transfer of market knowledge from Canada to developing countries, the effectiveness of small-scale projects, direct support to individuals in developing countries and the specific challenges facing diaspora youth.

Antonio Areaga and Miriam Egwalu shared stories that highlighted the bridging potential of diasporas. Photo: Greg Ehlers

The dialogue closed with comments from SFU professor of History and Latin American Studies, Alexander Dawson. Professor Dawson invoked the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (article 5) in highlighting the responsibility of countries like Canada to address poverty wherever it is found. In so doing, he cautioned the dialogue participants to avoid placing responsibility for poverty reduction at the feet of the diaspora. Furthermore, he urged participants to avoid emphasizing the specific to the exclusion of the general, and asked what role the diaspora might play in affecting policy change both here in Canada and in the developing countries with which they identify.

As the dialogue came to a close, participants began filtering out to the reception area and the conversation continued. In a dozen or more small circles people exchanged ideas and contact information. Some reflected on the ideas raised by Professor Dawson, others on how they could better engage with the diaspora in their own development initiatives and still others on how they might use their own diaspora connections to start engaging with development. Many were heartened and invigorated through connecting with others who are doing the same thing. This was the start of a conversation the Engaging Diasporas in Development project hopes to help sustain over the months ahead.

The January 19 dialogue was only the first in a series of 5 that will take place over the next 7 months. The next dialogue "Improving Health" will be held at the Morris J. Wosk Centre for Dialogue (580 West Hastings) on March 16, 2011. This dialogue will take as its starting point the question "What does being part of a diaspora mean to you and how does it affect your experience and understanding of health?" Participants will be encouraged to contribute to a discussion of the particular skills, knowledge and networks members of the diaspora can draw upon to improve health, both in Canada and in the other countries with which they identify. Through inclusive exchanges, the assembled group will explore the various efforts and initiatives currently underway and, crucially, will address the potential that may yet lie untapped. The goal will be to better understand how the connections or "bridges" diasporas form between one place and another facilitate change and improvement in health at both ends.

"My goal is to help all the kids who cannot afford school uniforms to be dressed up and go to school," writes Miriam Egwalu in the story that follows.

The Power of $100 | by: Douglas Olthof

Photo: Doug Olthof.

The following is a story by Miriam Egwalu...

My story started when I went to Uganda in March, 2009 after my Mom passed away. During the burial and afterwards, I noticed that there were more women than men. Most of the women were either very old or very young single mothers. The men were also very old or very young. I later realized that most of the men had been killed in the 25 year war that had ravished Northern Uganda and that the others had moved to towns and cities to try and find work, leaving behind wives to take care of the kids and grandparents.

When I interviewed one of the older ladies, she informed me that most of the women get no support from their husbands who have moved to cities and some are widowed with numerous children to support. She was one of the widowed. She was left with 6 kids to take care of. Her oldest daughter was not going to school because she needed her to help in the garden and other chores. The other 5 kids were being supported by a charity organization in order for them to go to school.

I asked her what I could do to help her be self-sufficient. She informed me that since she was now old, she could not do farm work like the younger women, and asked for 200,000 Ugandan shillings (an equivalent to $100.00 Canadian) so that she could open a store. I gave her the 100 dollars and went back to Canada.

I returned to Uganda last March with my 12 year old daughter to see how my Dad was doing and also to attend my mom's last funeral rights. I was amazed at how much the 100 dollars I left had helped this lady. She had a small stall by the road side and was busy selling small grocery items. She was also now renting a sewing machine and was earning money as a seamstress.

My daughter, who had never been to Africa before, wanted to see how kids her age were living and the schools they went to. She asked me why kids were going to school with ripped school uniforms and no shoes on. I told her that they could not afford new uniforms, so she immediately pulled out $25.00 Canadian dollars and offered it to the girl she had seen with a ripped uniform. She promised the head teacher that when she returned to Canada, she would baby-sit and walk dogs in order to help more kids get school Uniforms.

Photo: Doug Olthof.

When we arrived back here, we started saving money for kids who did not have school uniforms. I felt so good be doing something that my young daughter noticed and vowed to address. Today, we have managed to dress over 20 kids with school uniforms and thereby helped them stay in school.

I am planning to go back to Uganda this year in April and see how the project is proceeding. My goal is to help all the kids who cannot afford school uniforms to be dressed up and go to school because, although there is free elementary education in Uganda, no kid is allowed in class without a uniform and this is the main thing that makes kids drop out of school. Most of these kids live with aging grandparents or single mothers who have no way of getting any income.

I also plan to help one woman a year start some money generating project in order for her take care of her children.

I appeal to all who can help to join me in this project of dressing kids with school uniforms so that they can get the basic education needed by all.

Miriam Egwalu can be reached at: moballim2000@yahoo.ca

My Canadian experience inspires my development work in Sri Lanka

Author: Sumana Wijeratna| Posted: January 19, 2011A Sri Lankan immigrant to Canada writes about the experience of promoting development in her country of origin.

My Canadian experience inspires my development work in Sri Lanka | by: Sumana Wijeratna

Members of the Sri Lankan diaspora gather at Trout Lake, BC.

Nine years ago I arrived with my family in Canada. In Sri Lanka I worked with the Urban Development Authority as an urban planner in the municipal offices for eleven years and for another six years as the deputy director for regional offices.

After settling in the community of Surrey in 2002, I established VanLanka Planning Consulting where I continued to seek opportunities to use my experience in the international development field. In this quest, I reached out to the Vancouver-based International Centre for Sustainable Cities (ICSC) where I was able to offer my networks and local knowledge of Sri Lanka. This collaboration soon led to ICSC developing three successful community environmental management and sustainable planning projects in Sri Lanka that were funded by CIDA. I learned so much about sustainability planning from this experience and also believe my experiences were valuable to the Centre.

In 2007, when my younger son turned 13, he raised $500 to commemorate the death of my mother and pledged it to a charitable cause. This is a cultural practice for Sri Lankan people. My friends in Richmond contributed another $500 for the same. This small sum of money and the efforts of a volunteer youth group provided clean drinking water for 15 families and a computer resources center in a remote rural village in Sri Lanka.

Children pose in a "slum" area in Sri Lanka. Photo: Vanlanka Community Foundation.

In 2008, my husband and I used our combined Sri Lankan food preparation skills to engage the Sri Lankan diaspora in BC in raising $10,000 for the Kidney Hospital Foundation in Sri Lanka. This successful fundraising effort inspired me to continue my efforts in community supported programs for poor and vulnerable communities in Sri Lanka, and to establish the Vanlanka Community Foundation in April 2010.

Through the Foundation I work with private, government and community level partners in Sri Lanka and attempt to involve the Sri Lankan community here in the Vancouver area and the larger Canadian community in the activities of the Foundation. In 2010, with the help of ICSC and our food catering service, VCF was able to raise over $5000 towards our projects, which contribute to community economic development and education support programs.

Currently we work with three communities; one remote rural settlement in Thambavita, a tsunami and war-affected fishing community at Kallarawa, and a low income urban slum community in Wilgoda. Our key work areas are education, small business for youth, and women and food security. We were able to send Gregory Corcoran, a Canadian high school teacher, to Sri Lanka as the first volunteer teacher to deliver three free ESL programs for the poor children and one fee for service program to cover part of our expenses.

Members of a fishing cooperative in Sri Lanka haul in their catch. Photo: Vanlanka Community Foundation.

My eldest son, who was also inspired by the land of his heritage, pledged to work as a youth coordinator and raised $225 in 2010 that goes toward a project to research traditional irrigation systems in Sri Lanka.

My Canadian experience has given me a new way of being an urban planner. I have learned to get out and find out what people need. I am so privileged to be here in Canada where I can use my experience to bridge the gap between the rich and the poor.

To find out more about Vanlanka's programs, please visit their website.

Sumana Wijeratna is an urban planner from Sri Lanka whose networks back home and planning experience were valuable assets in her work as a project manager and the project specialist in sustainable community development projects in Sri Lanka. Sumana's experiences inspired her to start up community support programs for poor and vulnerable communities in Sri Lanka, and to establish the Vanlanka Community Foundation as a way to involve the larger community in her activities.

For more information please visit: http://vanlanka.com/index.html

'Being poor' surely means 'not having enough', or 'being deprived'? But not having enough of, or being deprived of what?

What is Poverty? | by: John Harriss

A farmer in West Bengal returns from ploughing the fields. Photo: Douglas Olthof.

I can well imagine many readers reacting to this question along the lines of 'What a silly question. Isn't it obvious?' Well, yes, it is, at least on one level. 'Being poor' surely means 'not having enough', or 'being deprived'? But not having enough of, or being deprived of what? The obvious answer to this question is probably 'Not enough money'. But then that only raises the question of 'Not enough money for what?' 'Not enough money' for some people, clearly, might be a fortune for others. This is particularly obvious when we think across societies. Poverty in our own society might still mean having all sorts of things, like television sets, fridges and motor cars that a poor woman in Lesotho, say, probably can't even dream of. So answering the question 'what is poverty?' really is a bit more complicated than we might think at first.

The standard definition of poverty – the idea of poverty that is referred to in the first of the UN Millennium Development Goals - is in terms of income. It says 'Halve, between 1990 and 2015 the proportion of people whose income is less than $1 a day'. Why $1 a day? This is because a good many years ago now it was reckoned that one dollar a day, or its equivalent, was just about the minimum that an average person required to be able to live at all. The reasoning behind this idea of poverty is that a person needs to have at her disposal goods or money enough (with which to purchase those goods) to be able to consume food and other essentials so as to feed herself adequately. It's a very minimalist notion of 'having enough', and not quite clear whether it includes an allowance for clothing and shelter, or keeping warm (which can be a problem at some times of year even in very warm climates … some people die of exposure every year, for instance in the North Indian winter).

In defining poverty, economists calculate how much it costs, in a given place, to purchase a 'basket' of essentials, to supply enough calories (which means dietary energy) for a person to be able to live. We think that it is calories that really count because if a person isn't consuming sufficient calories then protein-rich foods don't do them much good, because the body converts the protein into energy. A country's 'poor', then, are the people who cannot afford the basket of essentials for supplying the minimum amount of food energy.

This measurement of poverty involves all manner of assumptions and measurement problems, and so it is that even in India – the country in which most intellectual effort has gone into defining and measuring poverty – there are now several different more or less official measures of the numbers of 'poor' people in the country, ranging from about 27 per cent of the population to as much as 80 per cent.

But in any case, does income alone adequately define poverty? An Indian economist who studied villages around his home over a twenty-five year period found that according to the way of understanding poverty that I have just described, people got poorer. But when he talked to them about how they themselves thought of changes in their standard of living he found that in very many ways they reckoned they had got better off. They were able to eat a greater range of foods, for instance, their homes were more secure because they had locks on their doors, and they didn't depend any longer on landlords if they needed small loans. The people in the villages thought of poverty in terms not only of 'having enough income to survive', but also of 'having some assets (wealth in some form) that make for security over the longer run'. And last but far from least, they thought of poverty in terms of being independent – in terms that is, of having self-respect.

It is not enough, then, to think about poverty in terms of income alone. We need to think about other aspects of deprivation such as access to water, shelter, health services, education and transport. We need to think about poverty, too, in terms of debt and dependence – like those Indian villagers I described – and of vulnerability. The simple fact of having locks on their doors made those Indian villagers feel less vulnerable and more secure. But of course the idea of 'security' means more than just that simple physical security. Having some insurance against the bad times is also, quite obviously, very important, and very many people in the world don't have assets enough to provide them with any kind of insurance. Their livelihoods and their lives are therefore vulnerable. This is another very important aspect of poverty. There are others, too – such as the social disadvantage that many people experience because of some aspect of their identity – that they are from a low caste, perhaps, in the Indian villages I have spoken of.

A villager's passbook in West Bengal shows mandatory weekly payments against a very high-interest loan. Photo: Douglas Olthof.

Most generally, perhaps, we need to think about poverty in terms of powerlessness – or the inability to make meaningful choices and to lead a fulfilling sort of a life.

And what is it that makes people poor? And what makes a difference – what brings about the reduction of poverty?

Being poor or becoming poor is not, in general, because of choices that people make, but because of the circumstances in which they find themselves. The sort of economy that is growing and as it grows generates more secure jobs, so that fewer people depend upon casual labour, is very likely to make for less poverty. But much depends upon whether or not 'good jobs' are created – and one of the very worrying aspects of the growth of many 'developing' countries at the moment is that relatively few such jobs are being created.

Women in Southern India work on hand-looms, far removed from the country's booming high-tech economy. Photo: Douglas Olthof.

Economic growth is essential for the reduction of poverty. But it needs to be economic growth that generates productive and reasonably stable employment. It needs to be supported by the public provision of education that equips people to take on more productive work – and to deal effectively with the state so that they can secure what they are entitled to as citizens, from the state. Hence the second MDG: 'Ensure that by 2015, children everywhere, girls and boys alike, will be able to complete a full course of primary schooling'. And it needs to be supported by the public provision of basic health care, so that poor people have greater protection against those episodes of ill-health, and their consequences, that we know are so crippling for them. The MDGs concerned with child health and maternal health, and that aimed at combating HIV/AIDS, all relate to this further, vital, aspect of the tackling of poverty. And in all of this, MDG 3, about promoting gender equality and empowering women – 'Eliminate gender disparity in primary and secondary education, preferably by 2005, and in all levels of education no later than 2015' – is of fundamental importance. Female literacy pays very high dividends, we know, in terms of children's health and education, and in terms of civic action. Gender equality is of basic significance in the fight against poverty.

Click here to download the full version of the article.

John is a professor and the Director of the School for International Studies at Simon Fraser University.

QUICK LINKS