Updated for fall, 2005

We are usually willing to attribute our shortcomings to our environment, but we want credit for our achievements. Nevertheless, as a scientific analysis traces our behavior to our genetic and personal histories, less and less seems to remain for which we ourselves are responsible. That became the theme of Beyond Freedom and Dignity, which I published in 1971.... Time magazine did a cover story on it, and it was on the best-seller lists for many months. Reactions were both positive and negative, the negative in many cases quite violent. The Time cover had me asserting that "We can't afford freedom," and my title convinced those who did not read the book that I was indeed against freedom and dignity. But in spite of the scientific evidence that we are not in any way responsible for our behavior, it is important that we should feel free and worthy, and I argued that by recognizing the scientific facts we could move more rapidly to a world in which people would feel as free and worthy as possible. What lay "beyond" the freedom and dignity of the individual was the survival of the species or, more immediately, of a way of life in which the potential of the species was more fully realized.

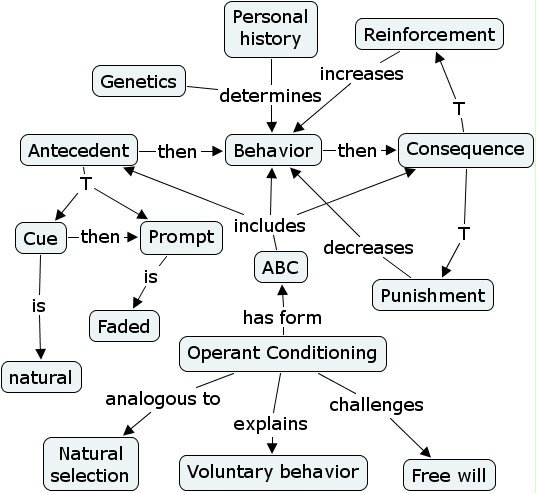

Similar to the way in which natural selection can evolve a complex anatomical structure like an eye, operant conditioning can produce complex behavior by reinforcing simpler but increasingly complex forms.

The application of operant conditioning in parenting, education and psychotherapy is called applied behavior analysis.

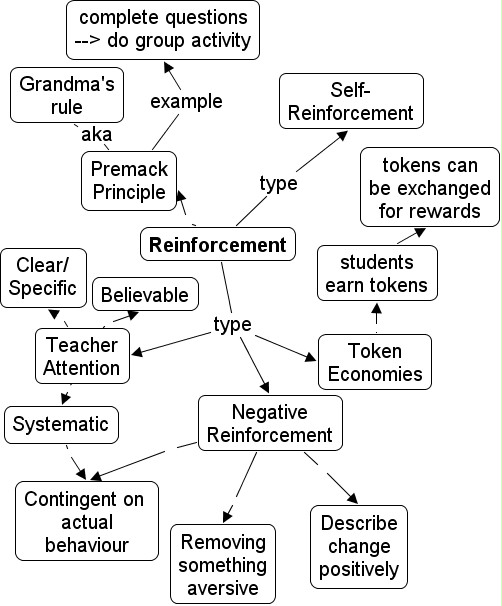

Use reinforcement. Avoid using punishment.

Assemble a repertoire of reinforcers.

Social recognition (attention) is often a powerful reinforcer.

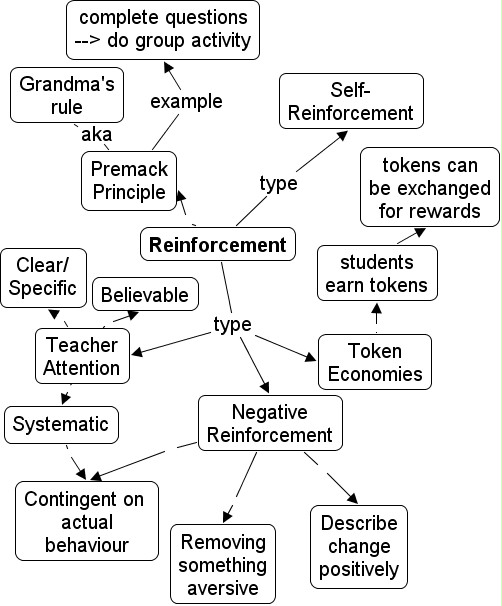

Use high frequency behavior to reinforce low frequency behavior (The Premack Principle).

Analyse the environment to identify cues.

Introduce artificial prompts and then fade them.

Reinforce behavior immediately.

Use tokens or verbal signals when it is impractical to deliver primary reinforcers immediately following the behavior.

Displace undesired behaviors with reinforced alternate behaviors (positive practice).

If a reprimand is necessary, avoid doing it in public.

If punishment is necessary, make it fit the misbehavior.

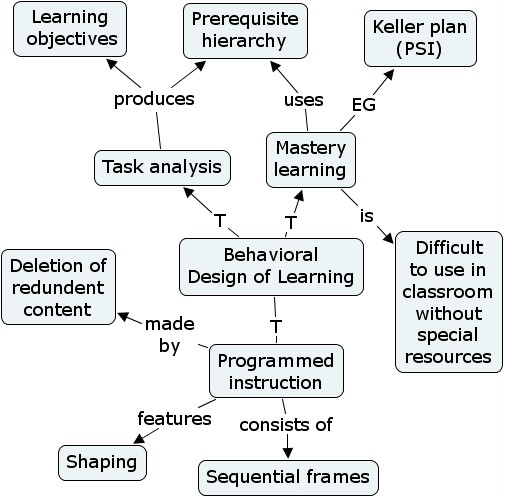

Analyse complex behaviors into simpler components (task analysis).

Reinforce increasingly complex assemblages of component behaviors (shaping).

Use group consequences appropriately.

In the language of operant conditioning, the instructions are prompts that are eventually faded. In the language of Vygoskian theory, the self-instructions are forms of private speech.

Many psychologists studying motivation from a socio-cognitive perspective believe that rewarding students can undermine intrinsic motivation. Self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 2002) proposes that when people are rewarded for doing a task, they have a lower tendency to perform the task after rewards are no longer available. It is argued that instead of using extrinsic rewards to motivate students, teachers should have students do activities that are instrinsically motivating.

Different reviews of the research on this question have produced conflicting results. A review by Deci, Koestner, and Ryan (1999) supported the position that extrinsic rewards are detrimental. Reviews by Cameron and Pierce (2002; 1996) support the view that rewards are only damaging in limited situations, such as when intrinsic motivation is already high.

Recent research by Cameron, Pierce, Banko and So (2003) has demonstrated that, in specific situations, rewards can enhance intrinsic motivation. Specifically, they found that people rewarded for progressively higher performance were more likely than others, who were either not rewarded or rewarded for a constant level of performance, to engage in the task in a free-choice session. These results are consistent with the theory of learned industriousness (Eisenberger, 1992) according to which rewarded effort leads to an increased tendency to expend effort.

What do you think? Should teachers avoid rewarding students for performance?

What is the proper role for intrinsic motivation in the classroom?

Cameron, J. & Pierce, W. D.(2002). Rewards and intrinsic motivation: Resolving the controversy. Westport, CT: Bergin and Garvey.

Cameron, J. & Pierce, W.D.(1996). The debate about rewards and intrinsic motivation: Protests and accusations do not alter the results. Review of Educational Research, 66,39-51.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (Eds.), (2002). Handbook of self-determination research . Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (1999). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 627-668.

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (2001). Extrinsic rewards and intrinsic motivation in education: Reconsidered once again. Review of Educational Research , 71, 1-27.

Eisenberger, R. (1992). Learned industriousness. Psychological Review, 99, 248-267.

Eisenberger, R., & Cameron, J. (1996) Detrimental effects of reward: Reality or myth? American Psychologist, 11, 1153-1166.

Pierce, W.D., Cameron, J., Banko, K.M., & So, S. (2003). Positive effects of rewards and performance standards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Record, 53, 561-579.