What is Physics?

It is conventional in a course like this to give you an answer to this question. I have to admit after many years of study, reasearch and teaching in what we call "Physics" I can't do it. Sorry. You may wish to leave now that you know how incompetent your instructor is but I will try to resolve the problem by quoting some other textbooks and professors on this topic.Physics is the fundamental science of the natural world. It tells us what we know about that world, how men and women found out what we know, and how they are finding out more today.Here's another try:

"Physics is what Physicists do."I really like this statement. Because the corollary is"Physicists are people who do Physics."This is my first example of a completely circular definition--it tells you nothing. Despite the fact that many textbook writers fill their books with circular definitions, I will try to avoid them.The second statement does tell you that physicsists are people which is something beginning physics students often have doubts about. Many people seem to think that physicists are strange beings who wear white lab coats, sit in windowless rooms by themselves and ponder complex equations that nobody else can understand and that have no relevance to our daily lives.

Actually nothing could be further from the truth. Physics has to do with the solid ground under your feet, and the distant stars which made the atoms in your body. It deals with air we breathe and the space and time in which we move. Almost every aspect of our daily life involves physics and it is a subject which everybody can and should know something about.

Aristotle and You

If we were to do a quick survey of how most beginning physics students think about the physical world we would find that we all have some ideas about it. Many of these commonly held ideas derive from "common sense" and correspond to the state of knowledge more than 2000 years ago. Physics is a Greek word and it was Aristotle who used it first (or at least he made it popular). If you type "PHYSICS" into a library's computer, you'll find Aristotle's Physics book is the earliest one they have.Aristotle was a student of Plato and wrote the first books on many of the sciences which we still recognize as academic disciplines. He was from Macedonia as was his most famous student: Alexander (the great).

Raphael The School of Athens.

In the center stands Plato (left) and Aristotle (right).

Click on the image to see a larger version.Well, Alexander did ok. Aristotle got a lot of things right and made a good start on many subjects. But his Physics had problems. It is useful to start in this historical way because all students have to overcome their misconceptions derived from "common sense" just as the human race had to overcome these same misconceptions. One of the problems when we begin studying physics is that what we are told in class doesn't agree with what we "feel" in our bones. It took civilization over 2000 years to change its ideas. We'll try to do it in 13 weeks.

Does This Make Sense?

It is curious that we can make sense out of the world. In other words, we can learn to see connections and relationships between phenomena which at first seem unrelated. It is also interesting how, quite often, some things don't make sense. Sometimes we reason from some obvious starting point to reach conclusions that don't agree with what we observe. Or perhaps we can reason from two different "obvious" starting points which lead to two different, contradictory conclusions. Then we know something is wrong with either our starting assumptions, or with the train of reasoning. One way science makes progress is by examining these inconsistencies in our world view and correcting them. Perhaps the starting assumptions are wrong. Maybe the methods of reasoning are wrong. Either way, finding and correcting misconceptons represents progress in science.

Free Fall

One of the most elementary and striking examples of this kind of problem is the law of falling bodies. Pick up two objects of much different weight and feel them in different hands. Think how much more force the heavier object is pushing down on your hand. Guess how much faster the heavier one will fall once it is let loose. Now let them go simultaneously. You can do this yourself with a penny and a two-dollar coin. Let them fall at the same time from the same height and listen for them to hit the ground. They make different sounds so you can tell which one strikes first. Do it.They hit at the same time. How can that be? This seems to violate our sense of what's right and we must figure out what's wrong with our ideas or else give up on making sense of what happened.

A Celt, a Basketball and a Tennis Ball

Another example of this kind of surprising result is the celt. If you set it rotating in one direction it rotates and slowly comes to a stop as you would expect. If you push it in the other direction it comes to a stop and then, surprisingly, starts turning in the other direction.

Two views of a celt.

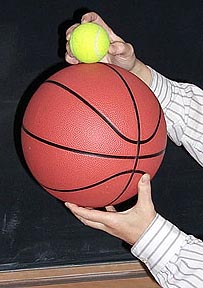

Position a tennis ball on top of a basketball. Drop them both. After the basketball hits the ground the tennis ball shoots up to a height much higher than that from which it started. Why?

How far does the earth move in 1 s?

Let's just examine one more example of something that doesn't quite make sense. You have been told that the earth rotates about its axis. The sun doesn't really rise and set, it stays in one place while we move around and around. Why don't we notice our movement? Perhaps we're moving too slowly to notice. We don't notice the hour hand on a clock moving do we? When we throw a ball up in the air it comes down in more or less the same place. Perhaps the earth doesn't move far enough for us to notice the shift in landing position during the short time that the ball is in the air.

So, how far does the earth move in 1 s? Let's figure. The distance from the N. Pole to the equator (through Paris) is defined as 10,000 km. The earth isn't a perfect sphere, but to some approximation the distance around the earth at the equator is about 40,000 km. The day is 24 hours long. Thus we move 40,000 km in 24 hours if we are on the equator. It's a little bit less in Vancouver. Thus the speed of a point on the equator is 40,000 km/24 hours which is 1667 km/h! How far do we move in 1 s? The conversion is done as follows:

Let d be the distance moved and s our speed and t the time .d = s t = (40,000km/24h x 1h/3600s x 1000m/km) x 1s = 463 m.

!

Problem: Look up the mean radius of the Earth's orbit around the sun. How far does the earth move in its orbit around the sun in one second?The Tale of the Travellers

The previous examples are things that don't make sense because our starting assumptions are incorrect. The famous tale of three travellers doesn't make sense to most people because their logical analysis is faulty.

Three travellers come to a restaurant and order the same meal which is listed on the menu at $10. After the meal the travellers each pay $10 to the waiter. The manager decides to give a discount and tells the waiter to give a $5 rebate. The waiter, reasoning that three people can't divide $5 equally, decides to keep $2 and give back $3. The travellers will still be happy to get a refund they had not expected and the waiter gets an extra $2 tip...it's win, win.Now the problem is this: The travellers have paid a total of $27 and the waiter kept $2. That totals $29. But the travellers originally paid $30. What happened to the extra dollar?

Get it?

The difficulty in analysing this kind of problem using words illustrates why mathematics is so important in physics. A logical and consistent mathematical approach allows one to correctly analyse such problems and to find errors of logic.

The Mechanical Universe Episode 1

This 30 min video gives a quick overview of the material in the first few weeks of the course and its historical pespective. There are two questions presented which were important in understanding how our view of our place in the universe changed. We have already discussed one of them: Why do falling objects fall straight down if the earth is moving so fast?The other question deals with the nature of gravity. If gravity, which causes an apple to fall to earth, also acts on the moon, why doesn't the moon fall to earth too?

By the end of this course you should be able to discuss intelligent answers to these questions.