|

| |

Major Acquisition

Now that you've got the hang of it,

here's the next prize:

The

Judeo-Christian library

#4

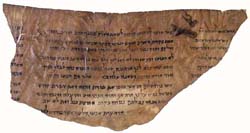

The Dead Sea Scrolls

Isaiah Pesher

A Pesher is a kind of commentary on the Bible that was common in the community that

wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls. This kind of commentary is not an attempt to explain what the

Bible meant when it was originally written, but rather what it means in the day and age of

the commentator, particularly for his own community. In the Isaiah Pesher, or commentary

on the book of Isaiah, a verse or verses from Isaiah are quoted. Then the commentary

begins, often introduced by the word "pesher," or "the interpretation of

the word..." If we were to write a commentary in this way today we might quote a

bible verse and then say, "and the meaning of the verse is..." and go on to show

the significance of the verse for our own church, synagogue, or society.

|

| Click the image to view an enhanced version.

|

This particular manuscript quotes several verses from Isaiah 5 concerning punishment or

destruction, and applies them to the "arrogant men" who are in Jerusalem. We

know from other scrolls at Qumran that the people who wrote many of the scrolls had

serious conflicts and disagreements with the religious leaders in Jerusalem over the

proper way to conduct worship in the Temple. Most scholars think that the community of the

Dead Sea Scrolls was led by a group of priests who thought that the Jerusalem priests were

corrupt. The group at Qumran therefore started their own community in which they tried to

live pure and righteous lives, away from th corrupting influence of Jerusalem. |

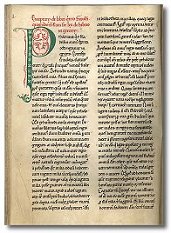

#5

HISTORY OF THE FIRST CRUSADE

by FULCHER OF CHARTRES, 1095-1106

Also included in text:

- GESTA TREVERORUM, THE HISTORY OF TRIER FROM CA. 2000 BC TO 1032 AD

- FRECULPHUS: CLASSICAL CHRONICLE, EXCERPTS: PTOLEMAIOS PHILADELPHUS, HERODUS ANTIPAS,

TROJAN WAR, FOUNDATION OF ROME, HISTORIES OF EPHESOS, BABYLON, CARTHAGE, CORINTH, NUMIDIA

AND JERUSALEM

- WILLIAM OF MALMESBURY: DE REBUS GESTIS REGUM ANGLORUM. THE HISTORY OF THE KINGS OF

ENGLAND FROM THE ANGLO-SAXONS TO HENRY 1

MS in Latin on vellum, Cambrai, Belgium, ca.

1160-70, , 31-34 lines in a very handsome late Romanesque book script of good quality by 4

scribes. Binding: France, ca. 1700, calf gilt over pasteboards, sewn on 5 cords,

red mottled edges. MS in Latin on vellum, Cambrai, Belgium, ca.

1160-70, , 31-34 lines in a very handsome late Romanesque book script of good quality by 4

scribes. Binding: France, ca. 1700, calf gilt over pasteboards, sewn on 5 cords,

red mottled edges.

Provenance(Owners) : 1. Premonstratensian Abbey of Bonne-Esperance, Cambrai,

Belgium (ca. 1170-ca. 1800); 2. Longman cat. (1816):6347; 3. Thomas Thorpe cat.

III(1823):16359; 4. Sir Thomas Phillipps, Cheltenham, Ph 237, (1822-1872); 5. Katharine,

John, Thomas & Alan Fenwick, Cheltenham, (1872-1946); 6. Robinson Bros., London

(1946-1978); 7. H.P. Kraus cat. 153(1979):19; 8. Sam Fogg cat. 14(1991):2.

Commentary: An eyewitness account of the first crusade in a MS made during the

2nd crusade. |

#6

The Gutenberg Bible

First book printed using moveable type |

|

|

The Printing of the Bible

Gutenberg experimented with printing single sheets of paper and even small books, such

as a simple textbook of Latin grammar, before beginning his work on the Bible around 1450.

In order to carry out these projects, he would have had to invent a printing press and

develop a method of casting individual pieces of metal type. Gutenberg's press was made

out of wood and could have been modeled on the winepresses used in the Rhineland vineyards

or on the papermaker's press. His type was made of a metal alloy which would melt at a

fairly low temperature but which could also stand up to being squeezed in a press. It was

long thought that Gutenberg had originated the punch-matrix-mold system of typecasting

used by typemakers for hundreds of years, but very recent research has cast doubt on this

theory. Quite possibly Gutenberg used a cruder system, casting his metal types not in

re-usable molds, but in sand or some other unstable medium. In any event, the process must

have been a long and laborious one, since nearly 300 different pieces of type are used in

the Bible.

The handmade paper used by Gutenberg was of fine quality and was imported from Italy.

Each sheet contains a watermark, which may be seen when the paper is held up to the light,

left by the papermold. The two watermark designs are the grape cluster and the bull's

head. Some copies of the Bible were printed on vellum (scraped calfskin). Gutenberg's

oil-based ink, made sufficiently thick enough to cling to the type, is exceptionally black

because of its high metal composition.

The number of presses in Gutenberg's shop is unknown, but the number of pages he needed

to print suggests that more than one press must have been in use. A skilled typesetter

selected the individual pieces of type for each line of the text and set them in a frame

(the forme), which was placed on the bed of the press and then inked with

horsehair-stuffed balls. A sheet of paper was slightly moistened before being placed over

the forme, and then a stout pull by the pressman completed the printing process.

No one knows exactly how many copies of the Bible were printed, but the best guess is

that around 180 -- 145 on paper and the rest on the more luxurious and expensive vellum --

were produced. A contemporary account by a visitor to Mainz indicates that the book was

nearly ready in October 1454 and available for sale by March 1455. Although the cost of

the book is not known, it would have been far too expensive even for wealthy individuals,

and so most copies were likely purchased by churches and monasteries.

A modern recreation of Gutenberg's type:

|

|

| The Question: Rorty steps back to give a sweeping summary of the history of

philosophy: Once upon a time we felt we had

to worship something that lay beyond the visible world.

Beginning in the 17th century, we tried to substitute a love of

truth for a love of God by treating the world of science as a quasi-divinity. At the end of the 18th century we tried

substituting a love of ourselves, led by the Romantic poets, to put science back in its

place. Our deep spiritual, poetic nature was

also seen as a quasi-divinity. Through

Nietzsche, Freud and Davidson, we took the next step towards trying not to worship

anything; nothing is divine and our language, conscience and community are seen as a

product of time and chance. (21-22).

Nietzsche has urged us to drop the search for truth; truth is a

“mobile army of metaphors” and we should forget trying to represent reality by

means of language. There is just no single

context for all human lives. Better to pursue

self-creation. For Nietzsche, “failure”

is accepting someone else’s description of oneself.

In acquiring knowledge of oneself through tracking down one’s specific

contingencies, like the “strong poet”, we can use words as they have never been

used before, invent our own vocabularies and therefore write our own stories. In that way we can dominate our contingencies and

“will ourselves to power” by getting control of our lives. (28).

In ancient Greek literature, and

especially in Sophocles, characters often saw themselves as victims of Fate or Chance.

Stories often portrayed the protagonist, in most cases a good man, besieged by

problems beyond his control. Literature at this time allowed people to

experience catharsis but it did not teach them how to cope with tragedy. We still

acknowledge tragedy may happen in an individual's life, but what do you think Rorty and

Nietzsche mean by dropping the search for truth? |

|