The

soundscape composition is a form of electroacoustic music,

developed at Simon Fraser University and elsewhere,

characterized by the presence of recognizable environmental

sounds and contexts, the purpose being to invoke the

listener's experience, associations, memories and imagination

related to the soundscape.

It grew naturally out of the pedagogical intent of the World

Soundscape Project (WSP) to foster soundscape awareness.

At first, the simple exercise of 'framing' environmental sound

by taking it out of context, where often it is ignored, and

directing the listener's attention to it in a publication,

broadcast or public presentation, meant that the compositional

technique involved was minimal, involving only selection,

transparent editing, and unobtrusive cross-fading.

This 'neutral' use of the material established one end of the

continuum occupied by soundscape compositions, namely those

that are the closest to the original environment, or what

might be called phonography or "found compositions".

Other works use transformations of environmental sounds and

here the full range of analog and digital studio techniques

comes into play, with an inevitable increase in the level of

abstraction. However, it is typical that the resulting sounds

are abstracted from the original, that is, by

retaining an aural or psychological relationship, and do not

become entirely abstract.

However, the intent of transformation is always to reveal a

deeper level of signification inherent within the sound and to

invoke the listener's semantic associations without

obliterating the sound's recognizability.

We will

present these categories as follows, with compositional

examples selected from WSP members including Hildegard Westerkamp

who has specialized in this genre, along with those by

composers who have been published by Cambridge

Street Records. However, we encourage you to listen to

works by the wide range of composers and environmental sound

artists working in the area worldwide.

A) A continuum of approaches

B) Fixed spatial perspective

C) Moving spatial perspective

D) Abstracted spatial perspective

E) Detailed analysis of specific soundscape

compositions

home

A.

A continuum of approaches. In a rapidly evolving field

that can be loosely grouped together as soundscape

composition, it can be expected that there is a wide range of

approaches. One way (and not the only one) to get an overview

of this range is to place it on the following continuum where

the approach mentioned above, phonography (by analogy

to photography) is placed in the middle.

The phonographic approach is rooted in Field Recording where the

intent is to document a particular place and its soundscape,

or at least certain aspects of it. There is minimal

transformation, and any editing or mixing is done transparently,

meaning that these manipulations do not attract particular

attention.

On the other hand, there are subjective choices being made at

every stage of the work – which are quite clearly demonstrated

in the Field Recording module with many of their dimensions –

and the field recordist never regards the material as

"objective" or "neutral". In that sense, the final result can

be regarded as a composition that can be listened to as if

it were music, that is, with the same attention one can give

to music (assuming it's not just background sound).

Given this concept of phonography, we can place it in the

middle of this continuum:

Sonification/Audification

<----------------> Phonography

<----------------> Virtual Soundscapes

mapping the

real

found

sound

abstracted sound

Sonification

refers to a range of approaches that map real-world

data onto sound parameters, sometimes termed auditory

display. Closely related is audification that

translates the data directly into sound, i.e. as a waveform,

though there are usually tricky issues of the time scale being

at audio rates, or needing to be transposed in some way to

accommodate human hearing.

Applications of sonification range from artistic projects

driven by scientific data in installations, sculptures, fixed

media works and concert pieces, such as the EcoSono projects

by Matthew Burtner, to those where artistically informed

design strategies are used to communicate scientific data to

the public. Today many such projects are driven by

environmental concerns, such as the work of Andrea Polli.

This range of approaches can be regarded as extending from

“science in the service of art” to its reversal as “art in the

service of science”. This distinction adds some clarity to the

more general term “environmental art” where the

question arises as to whether the environment merely serves

the artist (as material or context), or whether the art can

actually benefit the environment and public perception in some

way.

Phonographic approaches, as in the middle

of the continuum, are often based in environmental bioacoustics

or the practice of sonic ethnography with its social

and cultural focus. One of its main proponents, John Drever,

raises provocative questions about representation (of

what, how and for whom?) which are typical of contemporary

ethnographic practice – sonic tourism vs. a more involved

approach – that we raised in the Field Recording module. In

other words, are we creating just another illusion of

“fidelity”?

For instance, Gregg Wagstaff’s TESE (Touring Exhibition of

Sound Environments) field projects have incorporated community

involvement in recording and assembling a phonographic

style documentary of their community. Other sound artists

working in this vein spend a lot of time doing research and

actually living in a community while they are field recording.

They may also present their own audio representation back to

the community for approval.

The right side of the continuum, from phonography to what

we’re generalizing as “virtual soundscapes” with increasing

abstractedness, is what we will cover in this module. What we

can only refer to is the contemporary use of multi-channel

speaker rigs (often in multiples of eight channels in a

surround-sound configuration) that can provide a sense of

complete immersion in a virtual soundscape, including height.

However, many of the stereo examples we present here may

suggest that direction.

To summarize the general characteristics

of soundscape composition, here is an often quoted list:

- Listener

recognizability of the source material is maintained

- Listener's

knowledge of the environmental and psychological

context is invoked

- Composer's

knowledge of the environmental and psychological

context influences the shape of the composition at

every level

- The work enhances

our understanding of the world and its influence

carries over into everyday perceptual habits

Once you

start working with sound recordings and apply some of the

transformation techniques as covered in the Tutorial, you

realize that the recognizability of the sound object

can quickly be lost, or at least obscured. In many cases,

that doesn’t matter because the compositional intent is not

about the sound object in any semantic sense, but

rather it is about the sound as sound for its own sake.

The style of composition that results from this approach is

called acousmatic, which refers to sound where the

source is unseen, but to give it less of a definition of

absence, the sound itself is regarded as sufficient to carry

meaning. The formal practice of acousmatic music puts an

emphasis on the spectromorphology of sound,

literally “sound shapes”, as manifest through the timbre and

textures of sound, discussed in the second Vibration module

Therefore, the acousmatic approach moves sound towards an abstract

dimension where contextual references can be minimized.

Soundscape composition, on the other hand, wants to

integrate the sound source and the listener’s contextual

knowledge into the composition, and hence some degree of

recognizability is maintained, as outlined in the first two

points above. Listeners also may react by saying they

“participate” more while listening because of the

recognizability of the sounds they hear and what they evoke.

The third point about the composer’s knowledge influencing

the composition at every level is actually more challenging

in some ways. It’s certainly not the way instrumental music

is taught in the Western classical tradition, where a

similar degree of abstraction (as in acousmatic music) is

assumed and preferred. In fact, music with too much

real-world reference is termed “program music” and is

generally given less importance.

Soundscape composition, on the other hand, intends to bring

the complexity of the real-world (including the inner world

of memory, affect and symbolism) to bear on the

compositional result. Probably the best way to describe this

subtle process will be through the sound examples in the

rest of this module.

To put it even more simply: the soundscape composition is about

something in the real world, and listeners are invited to participate

more in listening.

The final point above about changing our perception and

understanding of the world can be traced to the idealism of

the young composer researchers working in the World

Soundscape Project in the 1970s, but the current concerns

for environmental issues have certainly re-kindled some of

that optimism and desire for making a contribution.

Whether or not soundscape composition (or any other

environmental art form, for that matter) will have any

lasting effects remains to be seen, but once you engage with

it as a recordist and sound designer, it is inevitable your

experience will carry over into everyday life. Your ears

will be tuned differently.

Moving beyond soundscape composition.

The notion of soundscape as how a sonic environment is

perceived and understood is generally associated with a

concept of place and the creation of acoustic space. A more

general umbrella term could be context-based composition

where the approach as outlined above opens up the references

to any real-world context and utilizes the entire

range of approaches outlined above. The intent is to be more

inclusive and to think about how we can use sound

effectively to address any other issue – essentially to

argue with and through sound.

Index

B. Fixed spatial perspective. There

are various structural types found in soundscape

compositions that derive from soundwalks, sound

monitoring, and field recording practice. The first of

these we will consider is characterized by a fixed spatial

perspective, similar to the exercise of sitting in one

place and monitoring all of the sounds one hears – a

useful exercise on any occasion, and one is often

surprised by what actually happens.

This basic perspective emphasizes the flow of time,

or else it can be a discrete series of fixed perspectives

possibly linked by smooth edits or cross-fades. Media

experience seems to result in listeners being quite

tolerant of simple transitions such as this without being

disoriented by the replacement of one soundscape by

another.

Variants on this format include time compression

(where the time flow is foreshortened by leaving out parts

of it, not a compression of the sound itself), as well as

those involving narrative or oral history

accounts that do not involve a soundwalk.

Again, the foreshortening of time seems quite

natural, not only because of media practice, but because

human memory does something quite similar. Recordists

notice this when they listen to a long take of events

they've recorded, and realize that those events now seem

to actually “take longer” than the way one remembers them.

We probably just remember the highlights, so to speak.

Memory is clearly not correlated well with clock time.

Since a soundscape is defined and treated as the perceived

sonic environment, then time compression and

foreshortening techniques may actually make the edited

recording seem more realistic, at least within certain

limits.

Layering in stereo or 8 channels.

We heard this first example in another module as a demonstration

of “soundscape fusion”, where four stereo recordings, all

done around Vancouver harbour, were mixed together as a

single fixed-perspective document in stereo. Although

there might be logical inconsistencies, most listeners

would accept this as a plausible phonographic

representation of the harbour, something that could

have happened this way.

But of course it didn’t. In the complete recording, done

for the 1996 Soundscape Vancouver double CD, the

intent was to produce a 4-minute recording of the harbour

that could be compared with a 1973 version on the other

CD, and the result was achieved by mixing four tracks

together.

However, if we had to forego any mixing or editing, that

would constrain us to a few minutes before and after noon

when the O Canada horn sounds daily. We would likely miss

other typical events that didn’t occur within this

restricted time frame, and hence our representation of the

harbour would be less inclusive.

Vancouver harbour mix

from Soundscape Vancouver 1996, CSR-2CD 9701

Reminder: if you want to follow along with

the enlarged spectrogram, use a Command

click on the image after you begin

the audio to open it in a new tab

|

Click to enlarge

|

Since we clearly had to choose which events to include,

and which not, the question arose as to “how many

seaplanes?”. The context here is that seaplane noise is an

issue for local residents living near the harbour. As

well, the harbour has the beautiful backdrop of the

coastal mountain range which is often snow-capped. The

physical environment is “picture postcard perfect” and

often used to attract tourists.

So, maybe if we were contracted by the local Tourism

Office, they might not want us to include any

seaplanes, and no doubt most listeners wouldn’t notice or

object to their absence. On the other hand, if we wanted

to “make a point” about seaplane noise, we could add a

huge number in order for listeners to get the message. So

how do we decide how to proceed?

A simple solution if we want to be

representative is to do a soundwalk in the area

first and make a count of the seaplanes we hear. This is

also a good idea for discovering what else to incorporate

into the mix that would be typical. As it turned out,

three seaplanes were added to the four-minute mix, as well

as number of boathorns and ending with the O Canada horn.

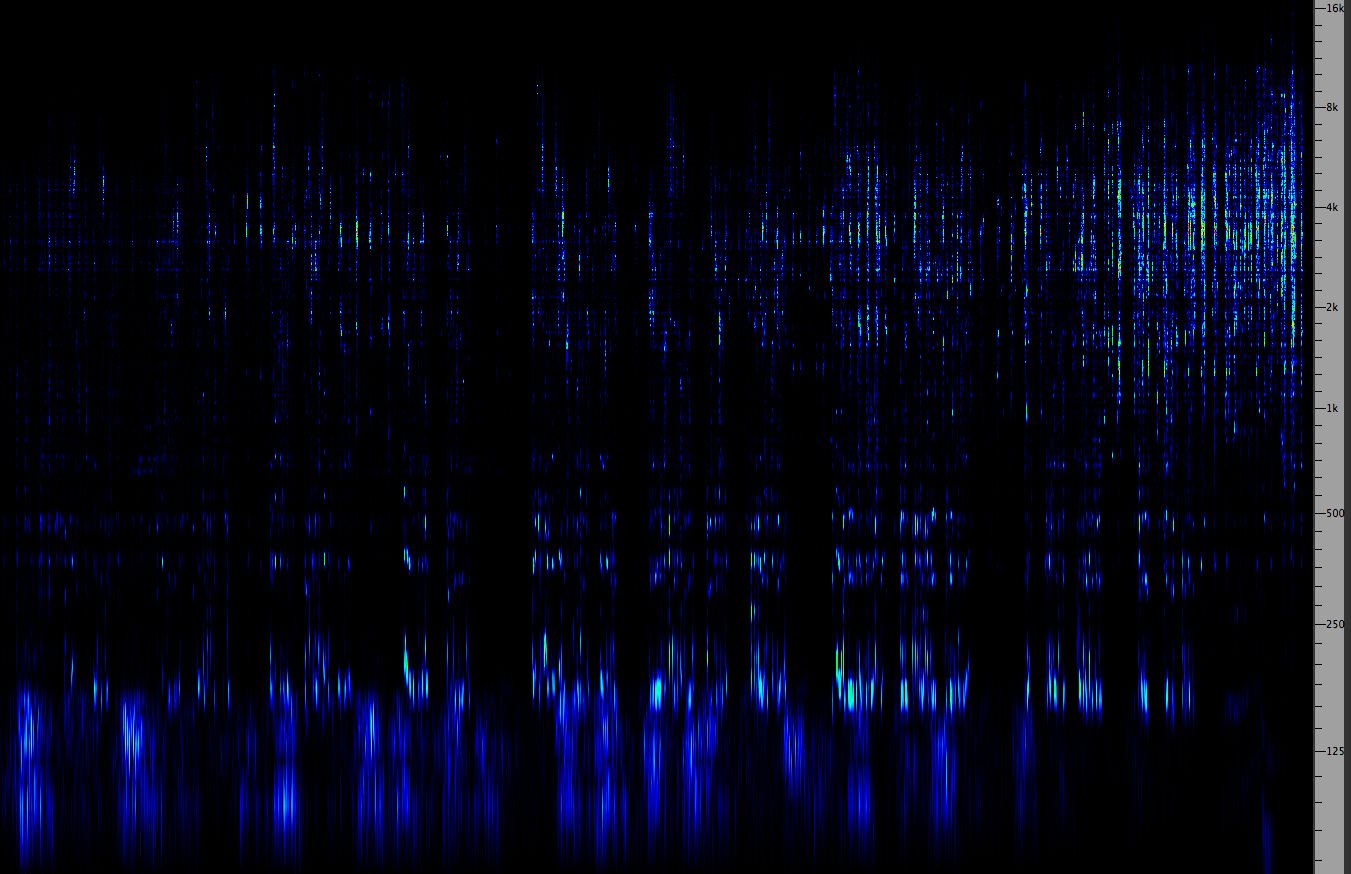

A similar approach was taken in my Pendlerdrøm

work from 1996, commissioned by a Danish group on the

theme of commuting, pendler being a commuter and drøm

being a dream. I was given one hour of excellent quality

recordings taken from the busy Central Station

environment, including the local commuter train that the

recordist rode on to get there. The commission was for a

stereo piece, but I had a digital 8-track Tascam playback

machine which could be mixed to stereo or 8-channel, so

both versions became possible.

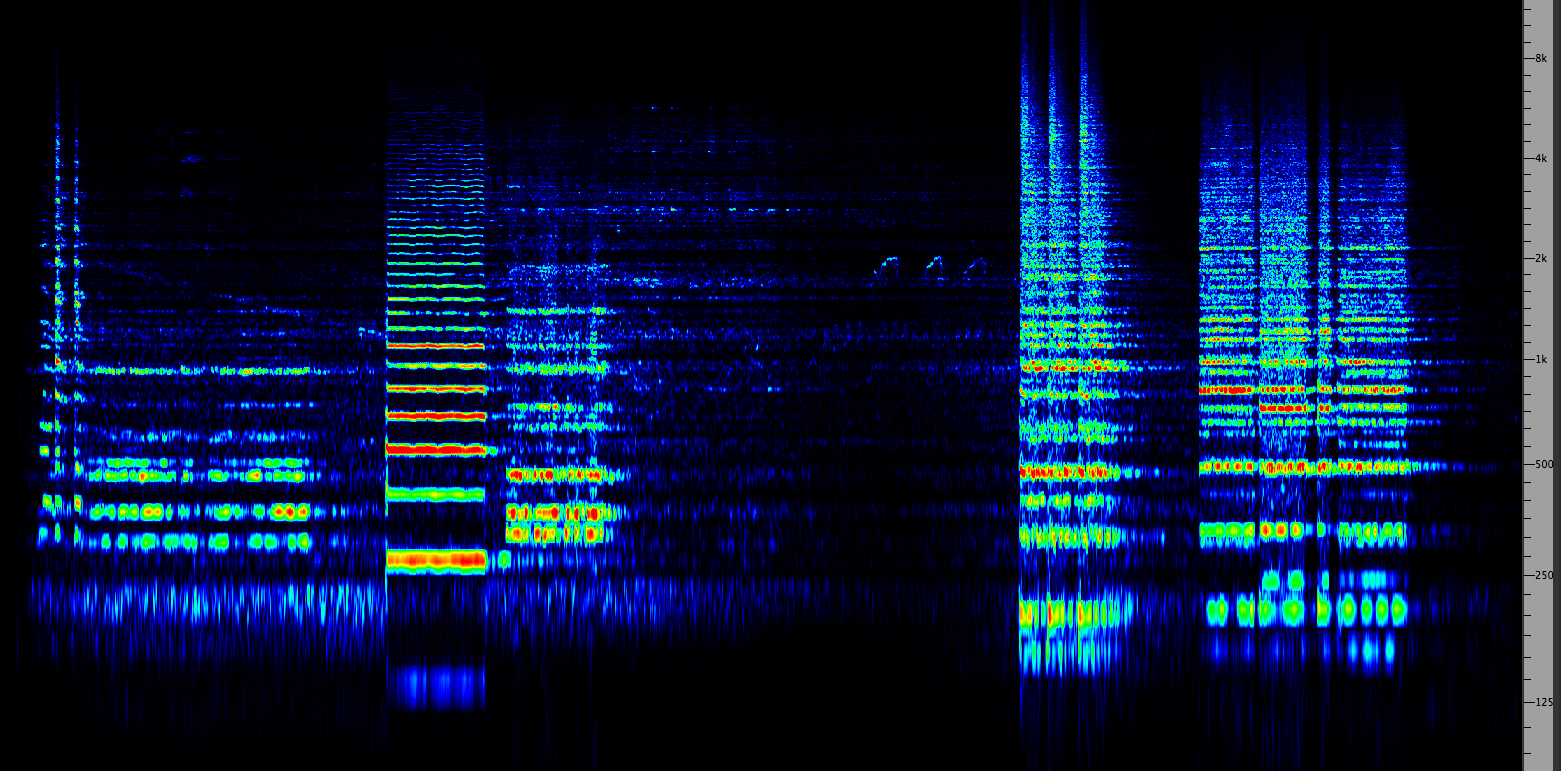

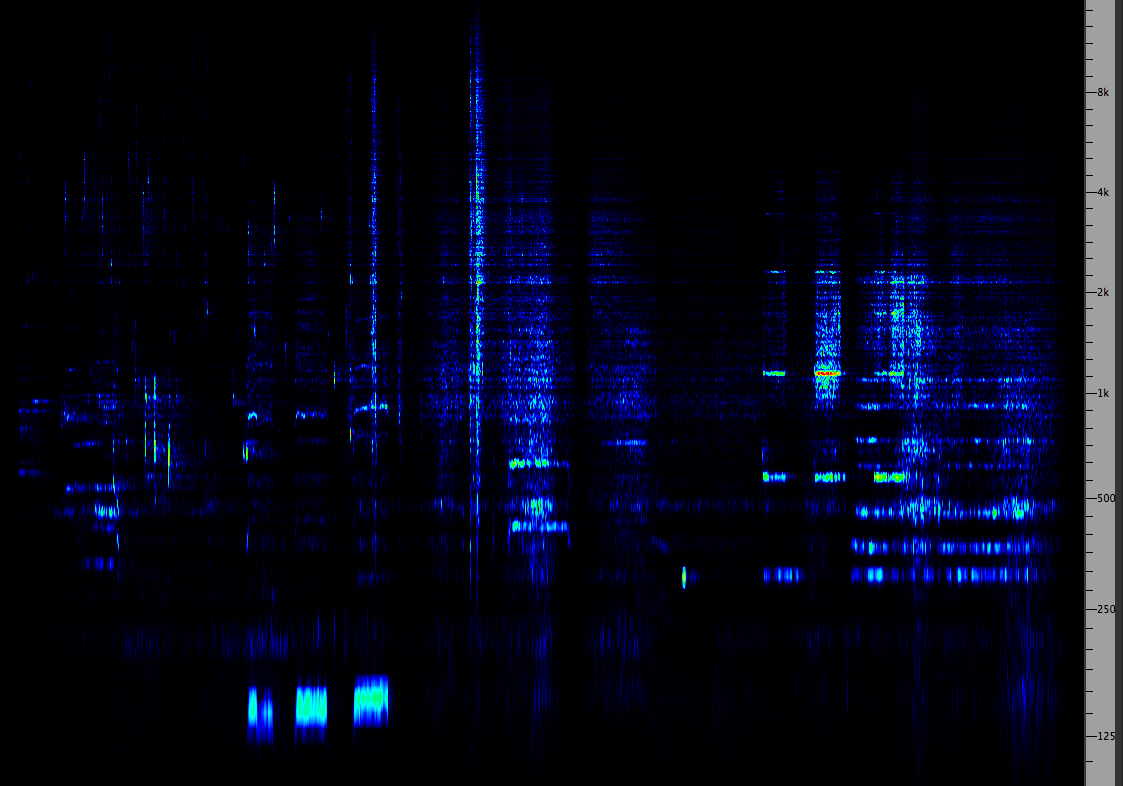

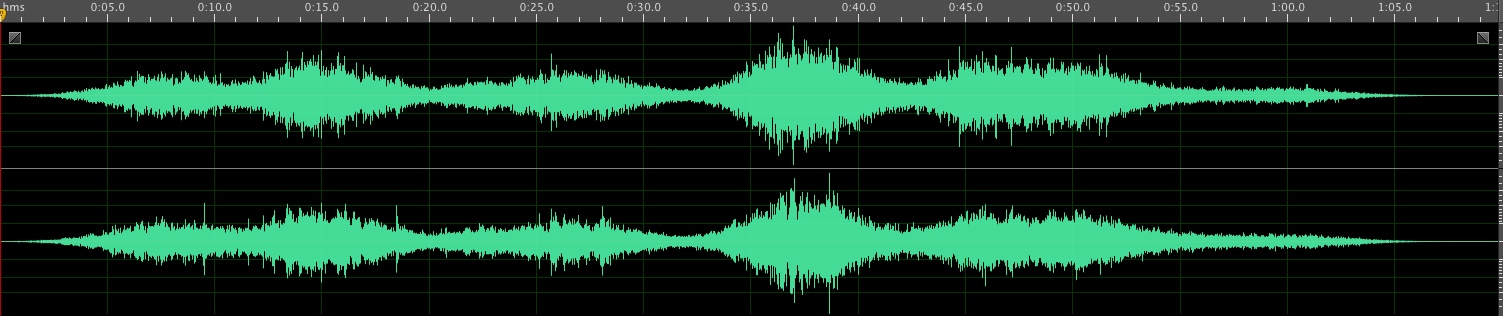

In the opening excerpt presented here, it was easy to

simulate the immersive environment of the station by

simply taking four original stereo tracks and

multi-tracking them, as shown below in the first

production page. For the first 40” there are just two

stereo tracks, before they are joined by two more, so the

density builds up. These tracks were from sequential

recordings, but together they fuse easily and suggest a

situation that was admittedly slightly busier, though not

atypically, than the actual station at the time.

Production score, beginning of Pendlerdrøm

(1996), Copenhagen train station sound files

All of the tracks are kept separate in the

8-channel format, except for tracks 3&4 which, being

mainly the public address announcements, could logically be

coming from multiple speakers. Normally for 8-channel work, it

works best to put stereo pairs in adjacent channels (ignore

the unusual numbering scheme in the diagram that was in use at

the time for our speakers). For the stereo mixdown,

speakers on the left go to the left channel of the mix, and

speakers on the right go to the right channel, and middle

speakers are panned to the middle, in case you’re interested.

We will return to the piece in the next section for an example

of moving perspective.

Opening

of Pendlerdrøm, simulating the busy train

station in Copenhagen,

from Islands, CSR-CD 0101

|

Click

to enlarge

|

The next

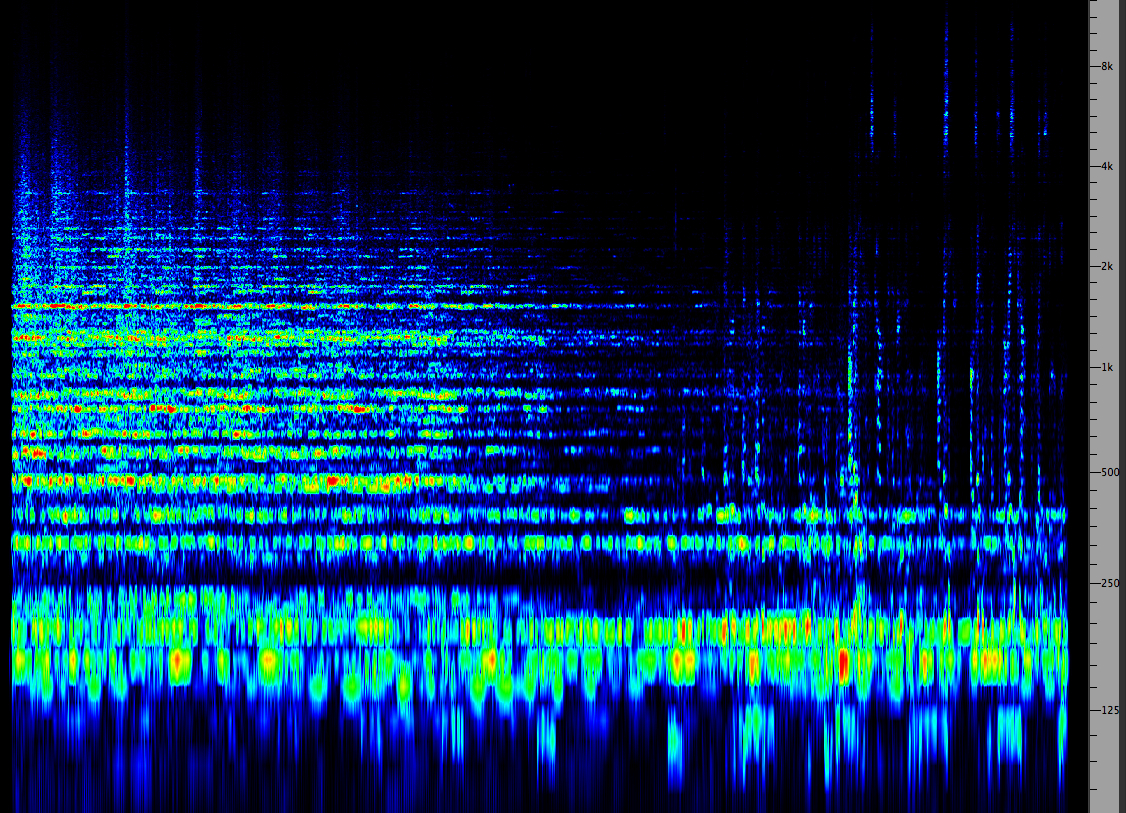

example from another 8-channel work Island (2000)

takes this approach a step further by multi-tracking and

mixing realistic and transformed materials. In fact, for the

8-track version, there are 8 tracks of short soundfiles of

individual waves on a beach, and 8 tracks of transformations

of them.

Here is the opening production score for the realistic sounds,

that arranges 5 different individual waves around the space

(N, S, E & W), plus two more of wave ambience as a

background. This pattern of waves repeats after 1 minute

(which you’ll probably only notice now that it has been

pointed out). The only processing is that there is a slight

exaggeration of the crest of the wave breaking clockwise to

the right which has been expanded by 90° to make it seem

broader.

Production score, beginning of Island

(2000), realistic sound files

Next we have the 8 transformed tracks, the

first four being high-pass filtered so that just the very

brightest component of these small wavelets is heard. These

sounds are also resonated with a Karplus-Strong

resonator with strong feedback. Tracks 3&4 are

transposed downwards by a fifth. The other four tracks are

low-pass filtered with the same resonator, but at a low

resonant pitch with maximum feedback to create a drone.

This drone at first seems out of place in a seaside soundscape

– the intent being to add an air of mystery to this imaginary

island – but in fact the same waves are triggering the rise

and fall of the feedback creating the drone.

Production

score, beginning of Island (2000), transformed sound

files

Production

score, beginning of Island (2000), transformed sound

files

Opening

of Island (2000)

from Islands, CSR-CD 0101

|

Click

to enlarge

|

The initial “attack” of the event, after a tentative start, is

a large ferry docked near the recordist, after which many

other boats join into a “steady state”, followed by a very

long “decay” as the participants drift away. This excerpt is

just the first few minutes of the entire sonic event.

New Year's

Eve, Vancouver harbour, 1980-81,

from Soundscape Vancouver 1996, CSR-2CD

9701

|

Click

to enlarge |

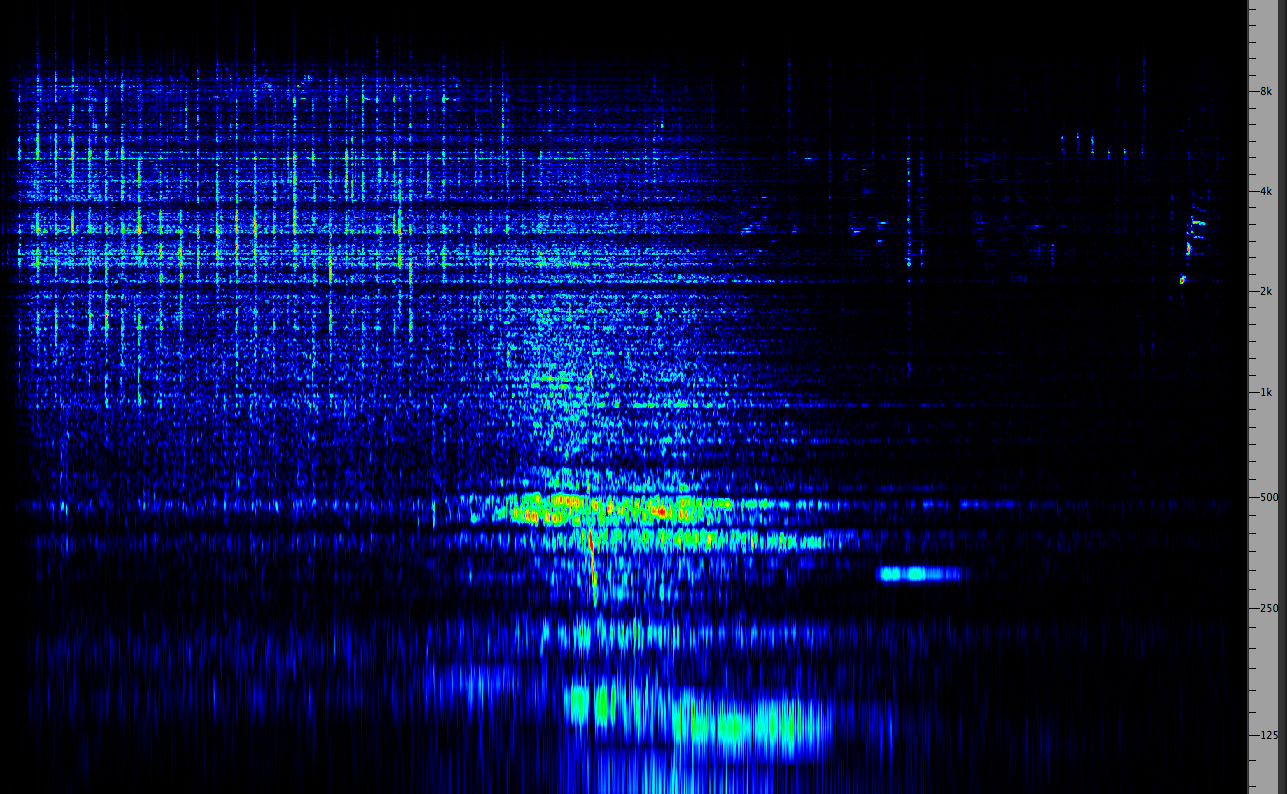

The

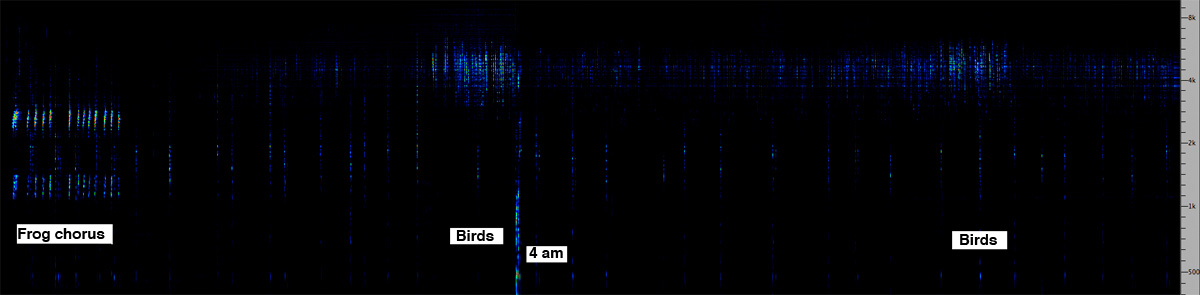

WSP's 24-hour “Summer Solstice” recordings in June 1974, were

done on the rural grounds of Westminster Abbey near Mission,

BC, where the birds and frogs around a pond formed an

ecological micro-environment. An edited version of these

recordings consisting of about 2 minutes per original hour was

broadcast on CBC Radio in stereo as part of the radio series Soundscapes

of Canada in October 1974.

The time compression for each “hour” was achieved with

transparent editing, with a short verbal announcement of the

time being the only commentary. Therefore, over the course of

the hour-long program, a listener could experience the

soundscape of an entire day at this site, something that would

be physically impossible for an individual to do.

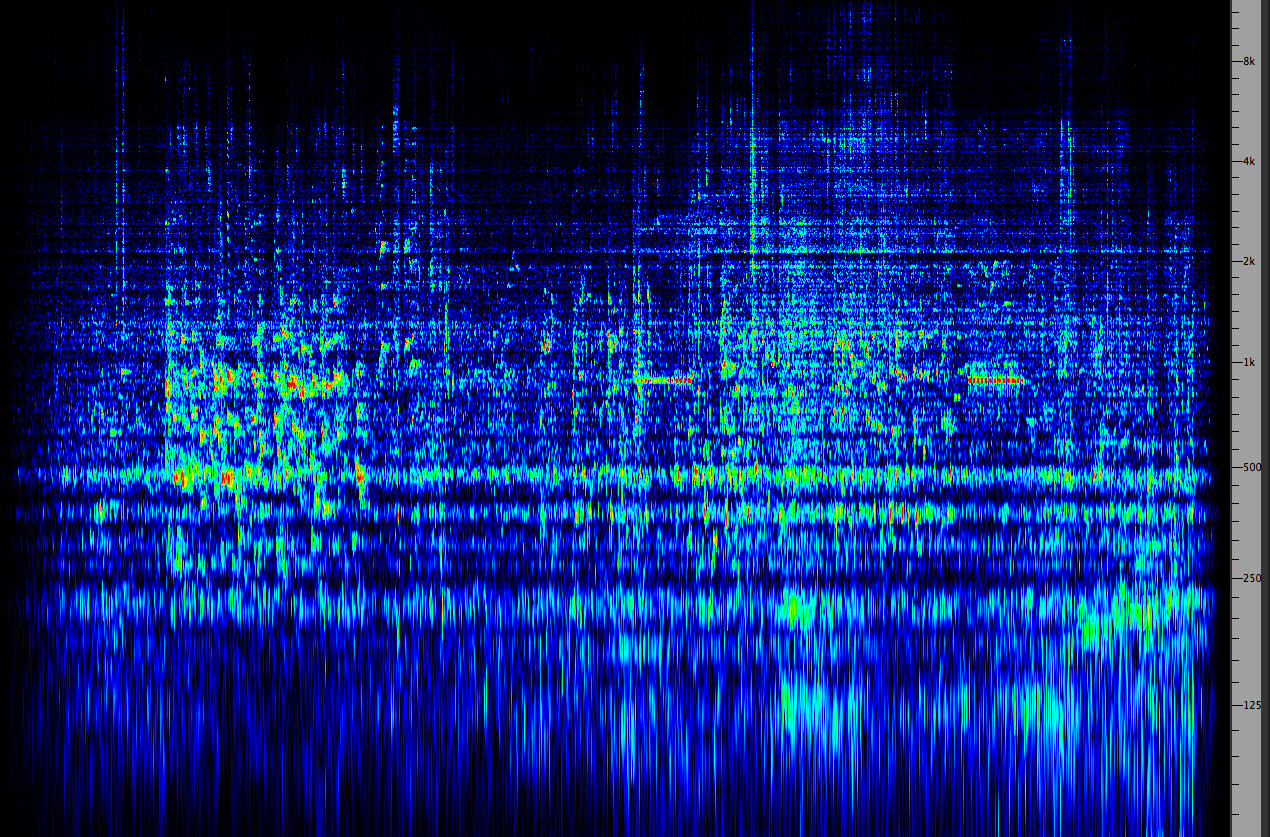

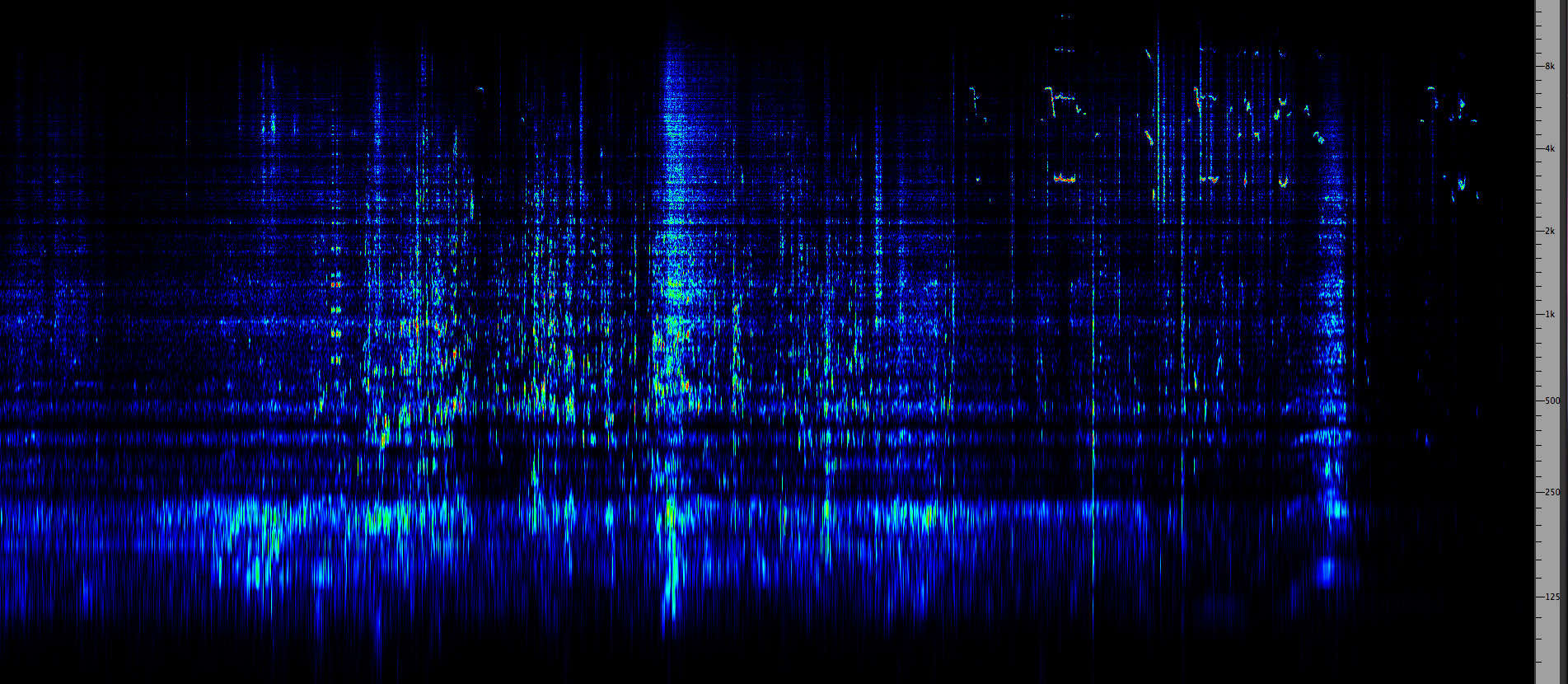

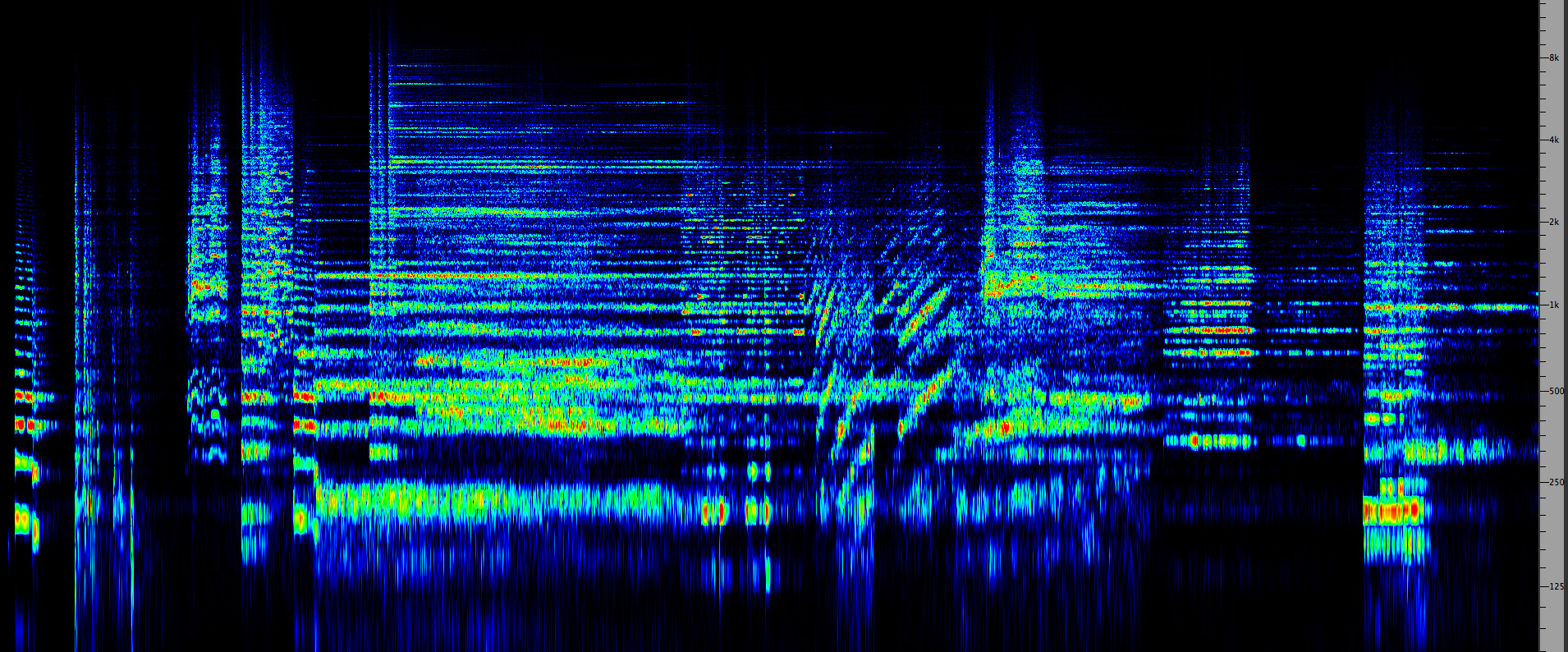

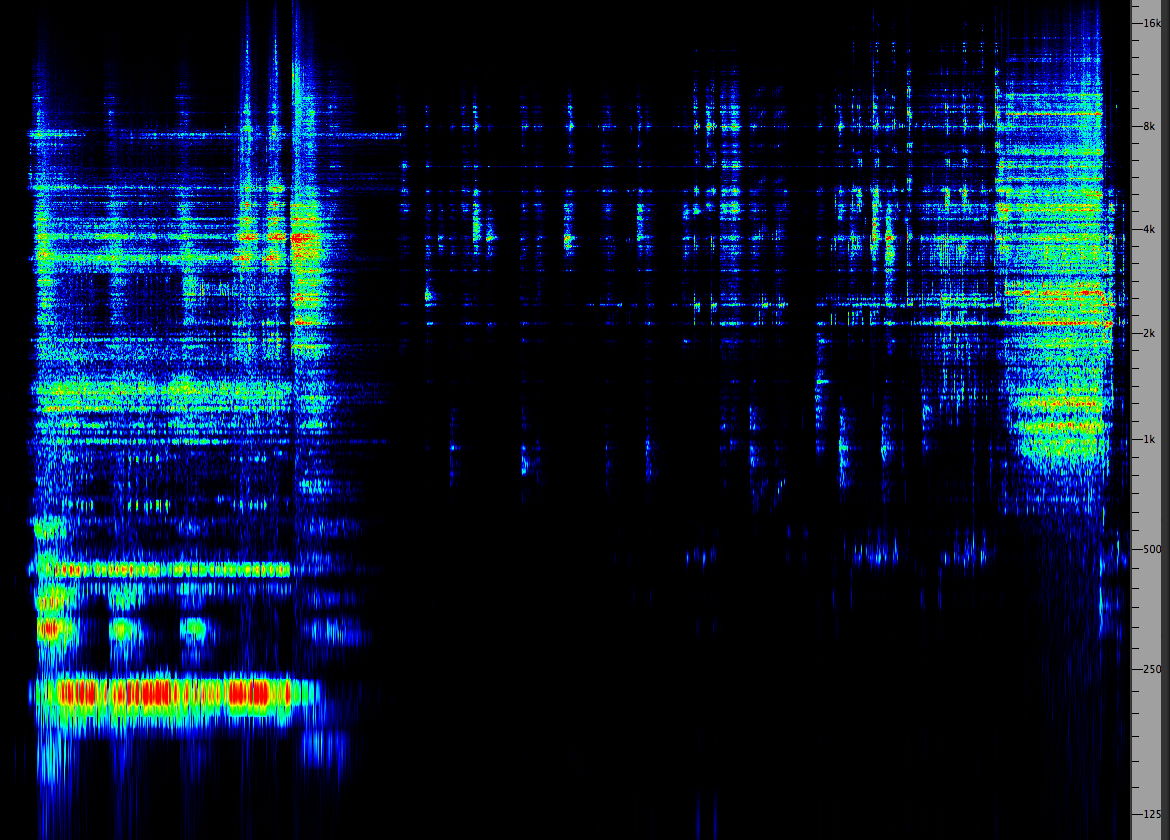

Summer

Solstice recording 3 to 8 am, June 1974

from Soundscapes of Canada

|

Spectrogram

of the period just before and after dawn (3:30 am)

showing frequency niches for frogs and birds

(click to enlarge)

|

Narrative, poetry and oral history.

These different types of verbal practices can be integrated

into a fixed spatial perspective and provide their own

rhythmic pulse.

We begin with Hildegard Westerkamp’s 1979 extension of her Whisper

Study that incorporates her reading a poem by Norbert

Ruebsaat “When there is no sound”, written in response to the

earlier version of her piece. The poem is matched to the sound

of icicles and footsteps in snow that originally appeared on

Hildegard’s radio program Soundwalking on Vancouver

Co-op Radio. Each element complements the other perfectly.

Excerpt

of Hildegard Westerkamp's Whisper Study (1979)

with a poem by Norbert Ruebsaat

from SFU-40, CSR-CD 0501 |

Click

to enlarge

|

My 8-channel

work Prospero’s Voyage (2004) imagines Prospero about

to leave his island, at the end of Shakespeare’s last play The

Tempest. The actor Christopher Gaze intones Prospero’s

last speech of the play as he addresses the audience,

beseeching them to “set me free”.

The soundscape is that of a storm (in the play, Prospero has

been able to command the elements) which at the end of the

speech breaks into a heavy downpour that pounds the roof and

is intended to sound like applause. However, note that the

actor’s voice has been placed into the reverberant space of an

actual theatre whereas the soundscape is clearly outdoors.

Does that inconsistency actually work?

Opening

of

Prospero's Voyage (2004)

with actor Christopher Gaze

from Spirit Journies, CSR-CD 1401

|

Click

to enlarge |

Bruce

Davis’ Bells of Percé was part of the Soundscape

of Canada broadcast in 1974 and is based on recordings

he (and Peter Huse) made in Percé, Québec, of the local

churchbells along with an oral history interview with

the parish priest.

This very poetic opening sequence filters the bells into a

cloud of partials through which we hear brief excerpts of the

priest’s stories about the bells, their names, and legends

associated with the region. The technique of foreshadowing the

main body of the piece with brief glimpses of the main

narrative sets the mood for the piece and suggests some of the

history, imagery and symbolism that is to come.

Opening

of Bruce Davis' Bells of Percé (1974)

from Soundscapes of Canada

|

Click

to enlarge |

Transitions between fixed perspectives.

As mentioned above, transitions in the context of an otherwise

fixed spatial perspective do not have to be “logical” in

either the time frame or how one has actually moved from one

soundscape to another. However, they shouldn’t sound too

awkward or abrupt either, unless a violent contrast is somehow

desirable.

In Hildegard Westerkamp’s Talking Rain (1997), the

opening section includes several rainy ambiences, all of which

have a different density and character. However, she avoids

the more usual technique of the smooth cross-fade to go from

one to the other. For one thing, it is easy to habituate to

the sound of rain and a cross-fade might only suggest a change

in its character, not a change in location.

Her solution, used twice, at first seems irrational because

the transition is signalled by a brief sound of a car passing

on a rainy pavement – a very urban type of sound (whereas the

other sounds of rain appear to be in a forest). However, each

transition works at the immediate level of drawing attention

to the change and making one more aware of the gentler texture

and lesser density of the ambience being introduced. On a

larger level of the entire piece, she is later going to make a

sudden transition to a noisy downtown rain-soaked street in

the middle of the piece, so these transitions foreshadow that

contrast.

Click

to enlarge either image

|

Two transitions from Hildegard Westerkamp's Talking

Rain (1997),

Earsay CD

|

Westerkamp

uses another type of foreshadowing to open her work Beneath

the Forest Floor (1992) where individual sounds and

gestures are introduced individually over a mysterious and

obviously transformed “thumping” sound, thereby creating a

suspenseful sense of anticipation while evoking a West Coast

rainforest. The unifying thumping sound keeps the perspective

fixed, but the brief encounters with other events suggest

transitions in time or memory.

Opening

of Hildegard Westerkamp's Beneath the Forest

Floor (1992)

|

Click

to enlarge

|

Index

C. Moving spatial perspective. A moving

spatial perspective involves a smoothly connected space/time

flow, in other words, a journey. The reference model is of

course the soundwalk, although it can be interpreted

much more broadly than that.

For instance, the sense of movement may be embodied in the

recordings being used, or it can be simulated by various

processing techniques, some of which are derived from the

acoustics involved. For instance, reverberation is a key

indicator of the nature of an acoustic space, and the ratio of

the direct signal to the reverberant portion is a strong cue

for distance perception, as described in the Sound-Environment

Interaction module, and the studio demonstrations in the

Reverberation module.

As discussed above, a simple cross-fade between recordings

often suffices to suggest movement, even if it is unrealistic

in terms of the time frame involved or the absence of aural

cues such as footsteps or vehicular movement. Panning in the

stereo plane can also be effective, although the “phantom

image” that this creates is not very stable based on one’s

distance from a stereo pair of loudspeakers.

Binaural recording builds

in both external localization and a recognition of the

recordist’s own movement. However, it is not always clear

whether the listener will identify with the movement they

sense, or whether they feel they are just observing someone

else.

On the more general level of a moving perspective is the

concept and experience of a journey. Throughout history, myths

have often portrayed both mundane and heroic forms of the

journey, usually with a level of symbolism as to what it means

in human terms. Likewise, the literary form of the novel

usually involves an evolution of its characters,

psychologically as well as physically. Journeys, for instance,

are often metaphors for a coming-of-age story, for instance,

or the search for some truth or goal.

So, with this degree of richness in the semantic

possibilities, what can be done purely with sound? Given its

disembodied quality, sound has the advantage of suggesting

both a physical movement in an acoustic space, and a mental or

internal type of movement through memory and the imagination.

The latter is usually suggested by a transformation of

realistic sounds, and not just the old film cliché of the

image getting blurred and the sound becoming heavily

reverberated!

Here we will explore a variety of approaches in the

electroacoustic domain.

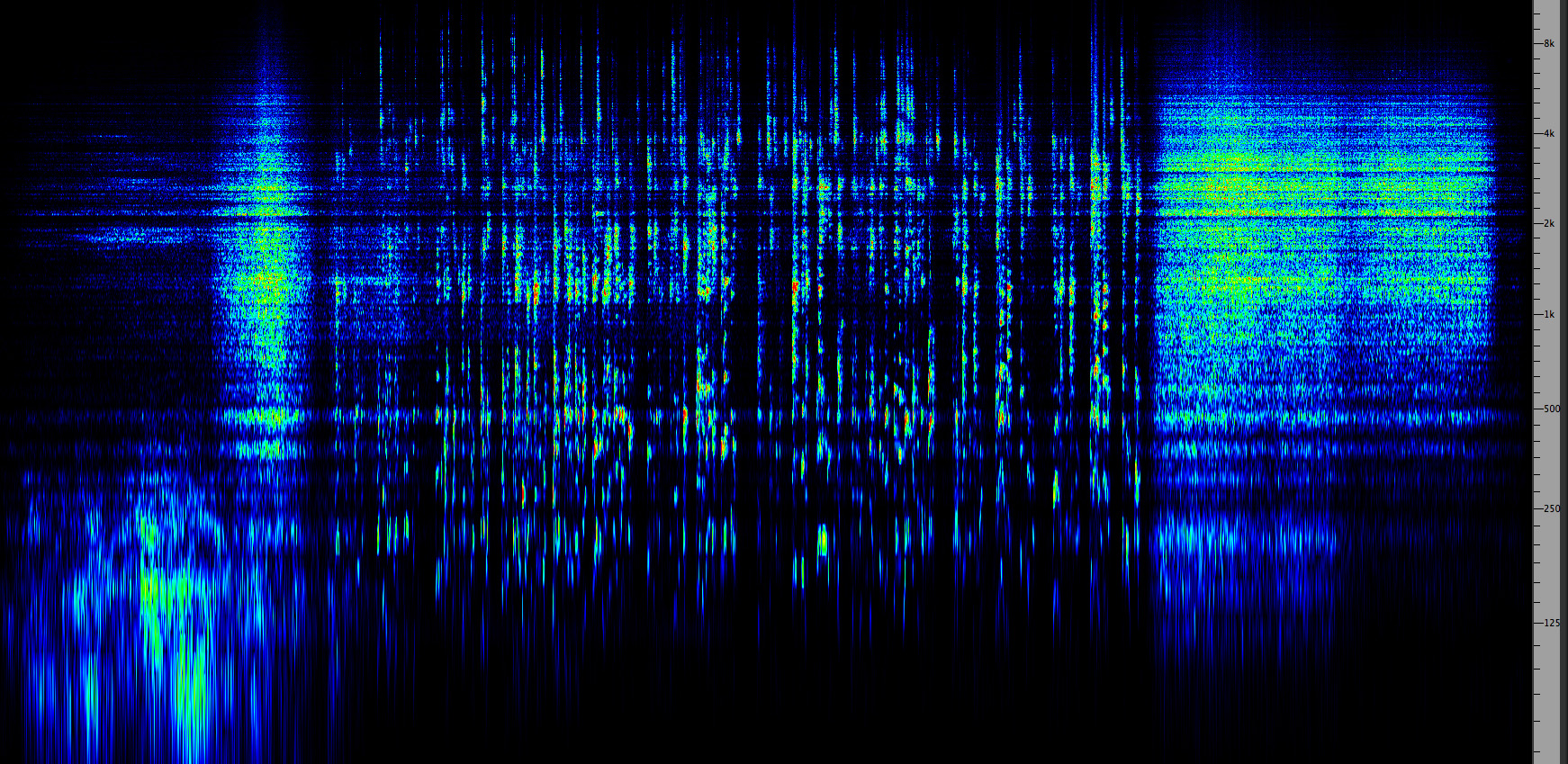

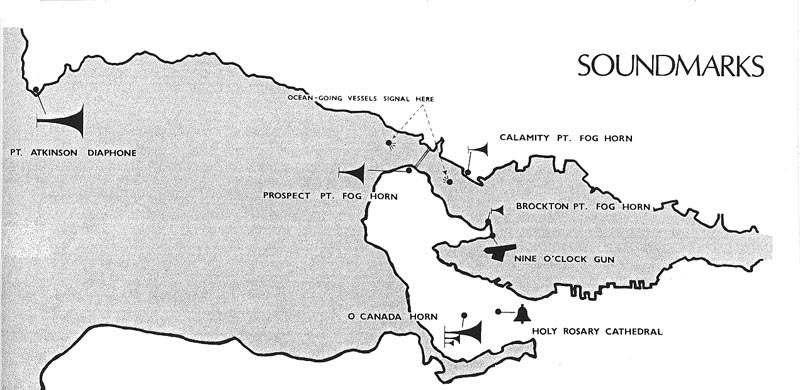

Classical cross-fade and reverb. The

first departure from the phonographic style of documentary

approach by the WSP, from edited field recordings towards a

more compositional approach, occurred with the preparation of

a track for the Vancouver Soundscape called “Entrance

to the Harbour”, published in 1973. The idea was to re-create

in sound a journey by boat from the outer limits of Burrard

Inlet, identified by the great diaphone (i.e. foghorn) at Pt.

Atkinson, a soundmark that dated back to the early 20th

century, past other foghorns at Prospect Point, Calamity Point

and Brockton Point, under Lions Gate bridge, into the inner

harbour. At the time, this trip could actually be made on a

ferry, since discontinued, and was familiar to many

Vancouverites.

Vancouver soundmarks, 1973

However, there were at least two problems. The actual trip

took at least a half hour, and when the recordists rode on the

ferry, they only got boat noise. However, they also had

recorded the various foghorns separately as part of the

documentation of sound signals in the area, and could easily

record a typical docking procedure, including passengers

meeting friends and picking up their luggage in a very small

room with a squeaky door. Using these elements and some wave

ambience, they attempted to simulate the trip in a 7’ mix

using the simplest of cross-fade techniques and changing the

levels of the various horns so that they appeared to approach

and recede in the distance.

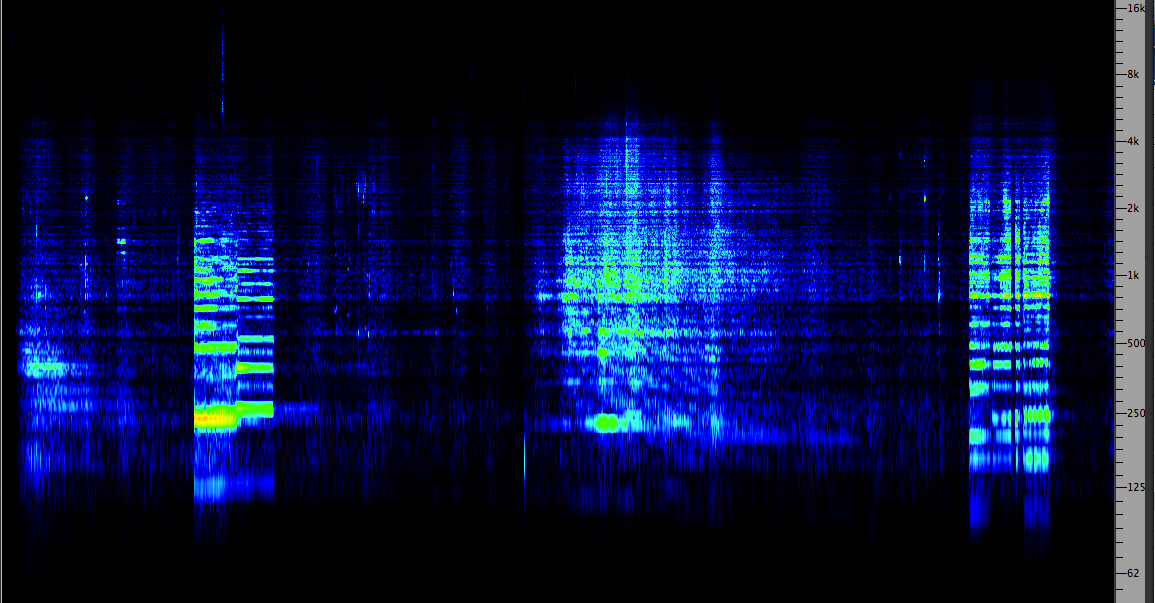

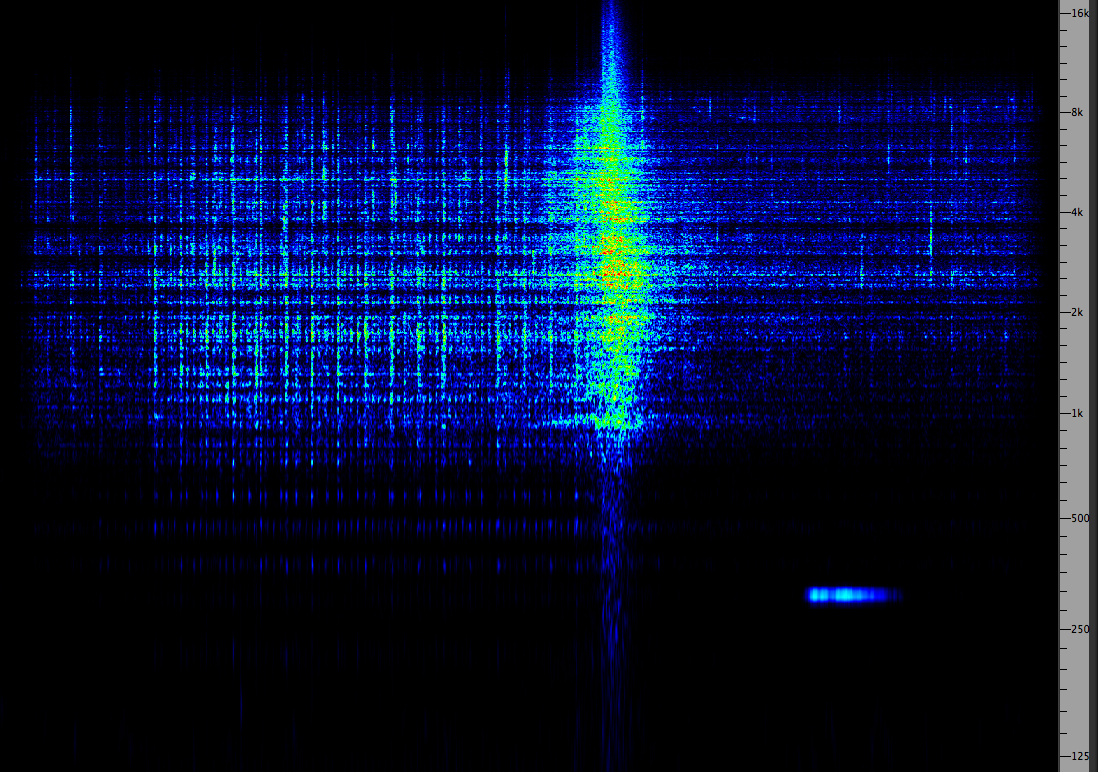

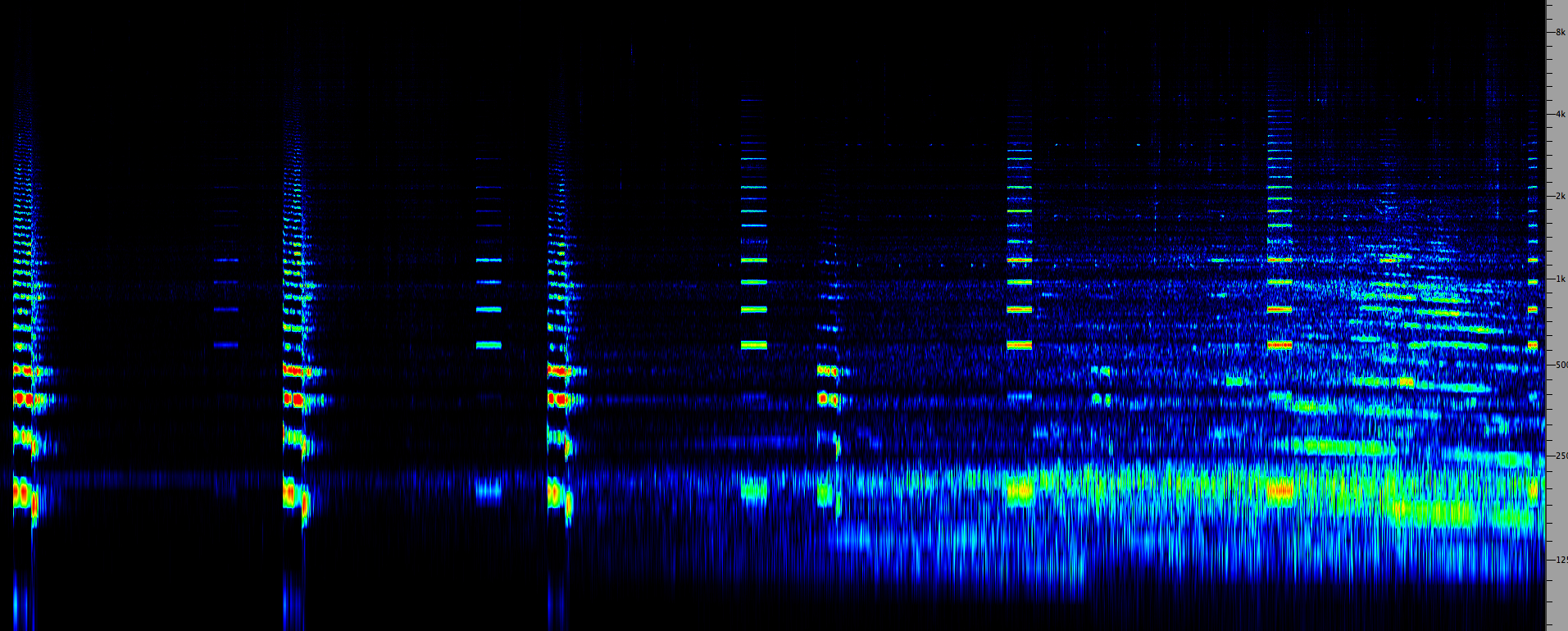

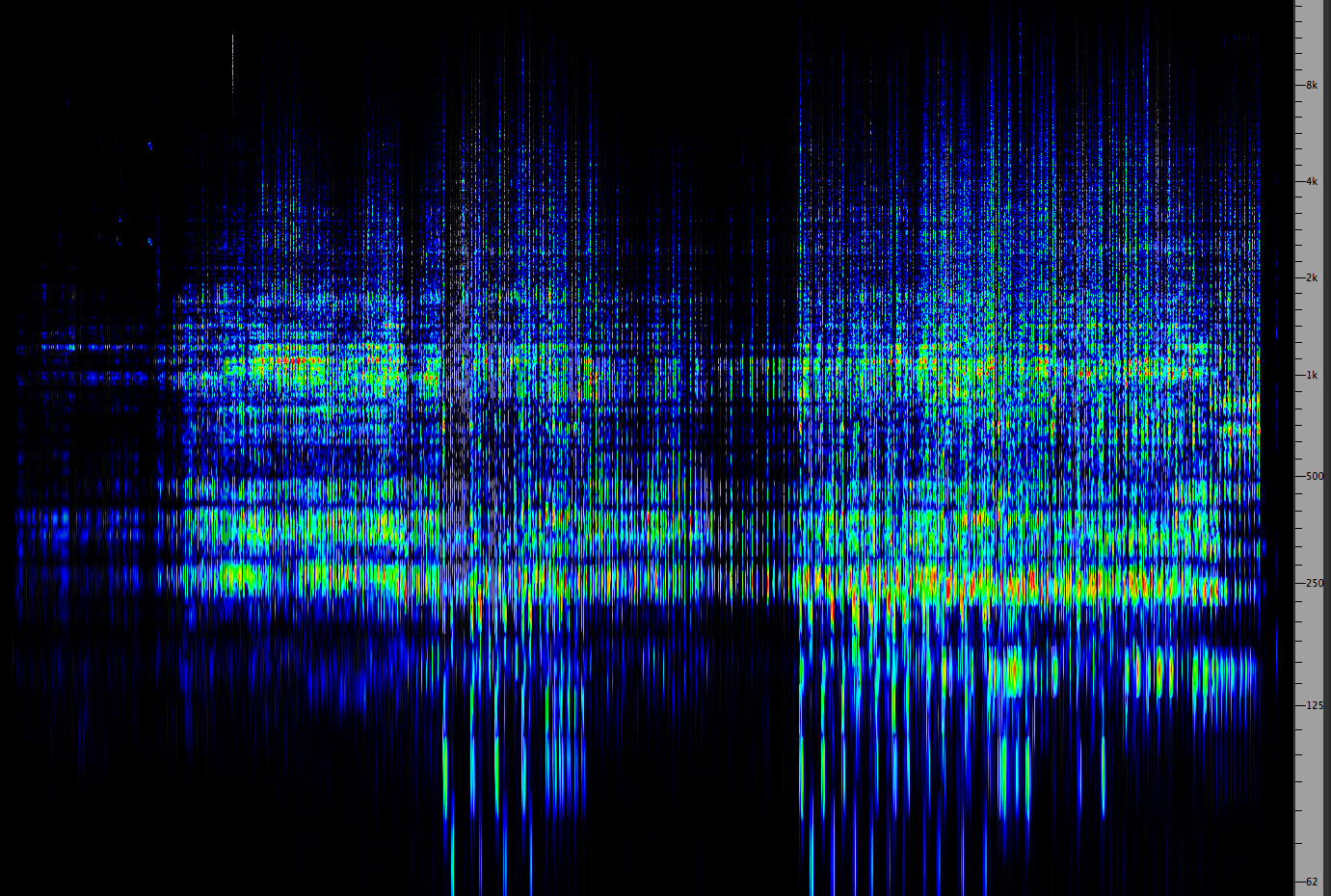

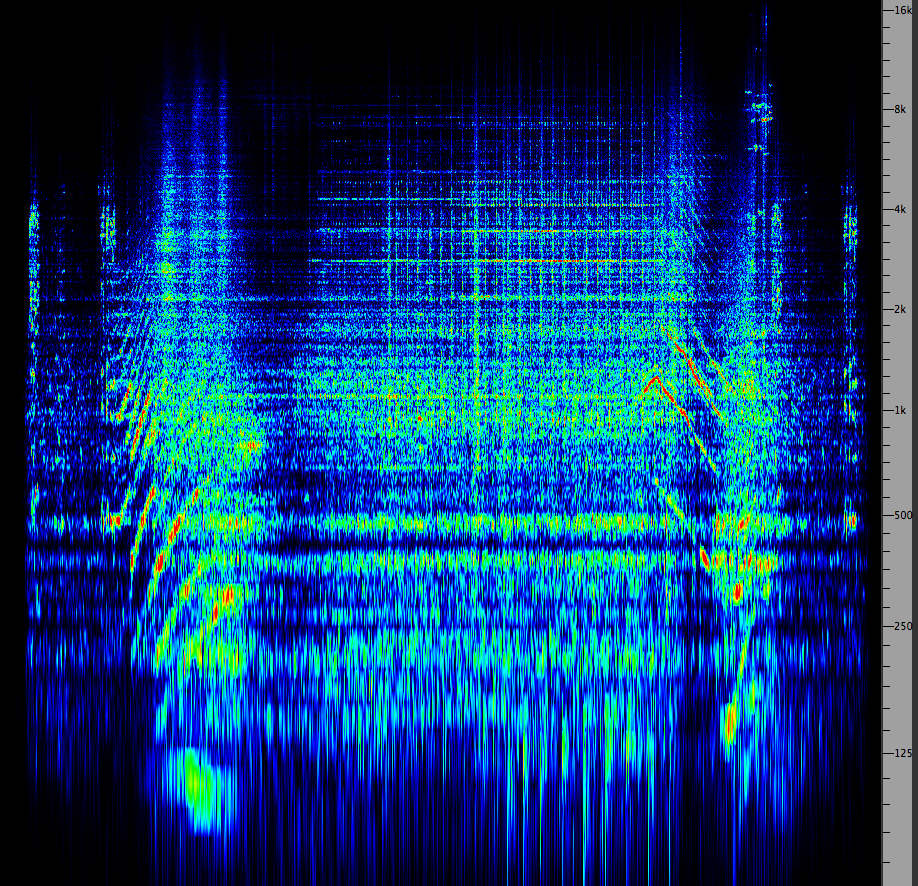

Spectrogram

of part one

Entrance

to the Harbour, Vancouver Soundscape 1973

CSR-2CD 9701

|

Spectrogram

of part two

(click either image to enlarge)

|

By today’s standards, the mix is quite crude

with illogical elements (the waves are clearly on the shore,

even as we imagine being on a boat, and the transition to the

docking sequence is fairly abrupt). Since the studio didn’t

have a proper mixer at the time, only rudimentary level

changes were possible. However, the foreshortening of the trip

to seven minutes and the illusion of approaching and passing

the foghorns, as well as the bridge and its traffic noise,

were strong enough cues to make it seem realistic.

The track can appear to be a phonographic style documentary

despite its flaws, but closer examination also shows a

compositional structure based on the journey format that has a

strong character. The beginning with the reverberation of the

foghorn off the mountains and across the water suggests a wide

open space and the natural geography of the area. Human sounds

don’t appear until the docking sequence, and indicate that we

are now entering the city itself. At the very end, the space

we are in (small and acoustically bright) is the very opposite

of where we started, suggesting a narrowing of the acoustic

space from very large and open, to enclosed and domestic.

Using a parallel circuit. The parallel

circuit, as described here,

involves splitting a signal into multiple versions, each of

which can be processed separately and mixed back together. A

simple example of this would be a cross-fade from the original

sound to a processed version. In my work The Blind Man

(1979) I cross-faded the original WSP recording of the

bells of Salzburg Cathedral – a very rich mix of seven bells –

with a filtered version of them that essentially removes the

attacks so we hear just the resonant partials. A description

of this analog process and the French studio where it was done

is presented here.

Text fragments from the poem by Norbert Ruebsaat were added to

the bell mix, as heard next. In particular, the line “already

it has come and is leaving again” – intended to describe the

wind – is reflected by the bells which have rung, but then

without their attacks seem to have left, leaving only their

memory and resonances. Mirroring a text with an appropriate

sound transformation can be quite satisfying, and help

listeners understand the text on multiple levels.

Bell and text sequence from The Blind Man (1979)

on Digital Soundscapes, CSR-CD 8701 |

Click

to enlarge

|

Layering

the part and the whole. In La Sera di Benevento

(1999), the soundscape begins in the local train station

in Benevento, Italy, with a train arriving. A smooth

transition in the train sounds which are increasingly

resonated takes us into a kind of daydream with a fountain and

afternoon cicadas. Can you spot the first transformed sounds – hint, there

are two.

Opening

of La Sera di Benevento (1999)

on Islands, CSR-CD 0101 |

Click to enlarge

|

The first transformed sound in the above

example is actually the squeaky wheel from the train at 0:29

which is looped and mixed with the train – a kind of

repetition that is entirely plausible with trains, even though

this squeak actually happened only once. The second sound is

the whistle at 0:39 (the same one heard first at 0:12), but

this time it is granulated, then stretched, which is where

most listeners will identify a transformation. Listen to the

opening again to hear how that worked.

The squeaky wheel is resonated, similar to the example above

from Island, on pitches that are consonant with the

horn, so that by 1’ the resonant drone takes over. There is a

brief lull at 1:30 as the cicadas are introduced, and then

we’re back to the train horn and drone. An Italian poem is

introduced later. The intent is to lead the listener seamless

into a daydream on a hot afternoon in southern Italy.

In fact, the repetitive rhythms of trains passing (called ostinati

in music) are very tempting to process, since a simple loop

taken from them is easy to edit out and repeat in synch with

the original recording. A slightly more complex version of

this parallel processing (by multi-tracking) was used in Pendlerdrøm,

introduced above, with much larger trains in the Copenhagen

station.

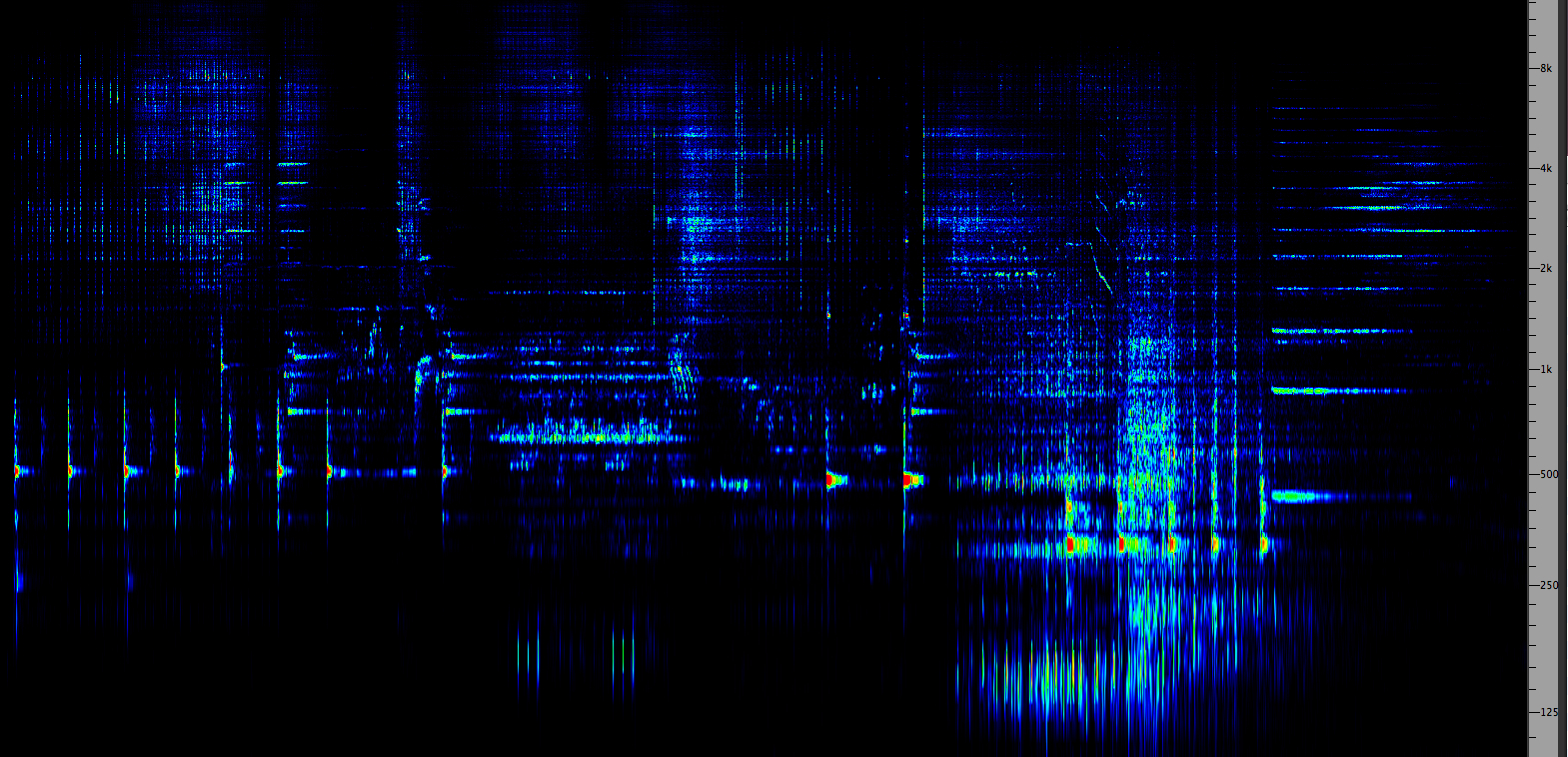

In fact there were two such loops used simultaneously, as

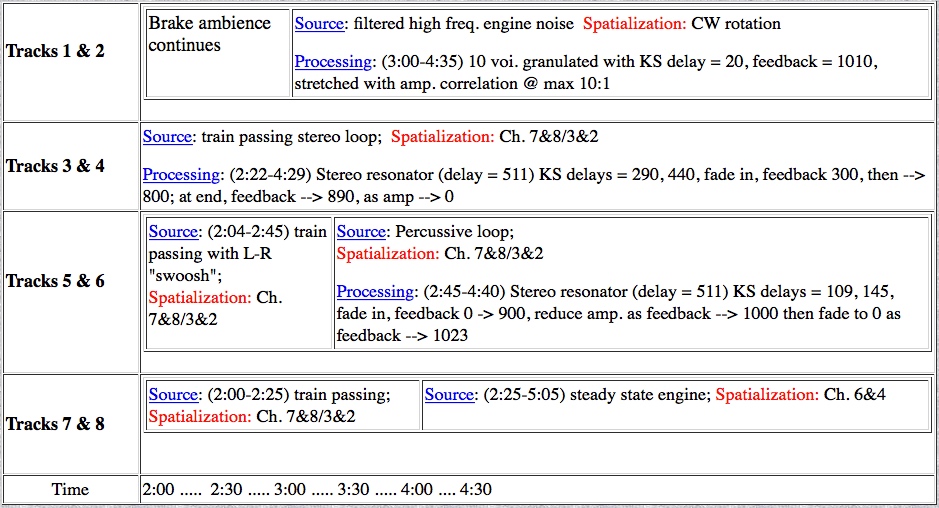

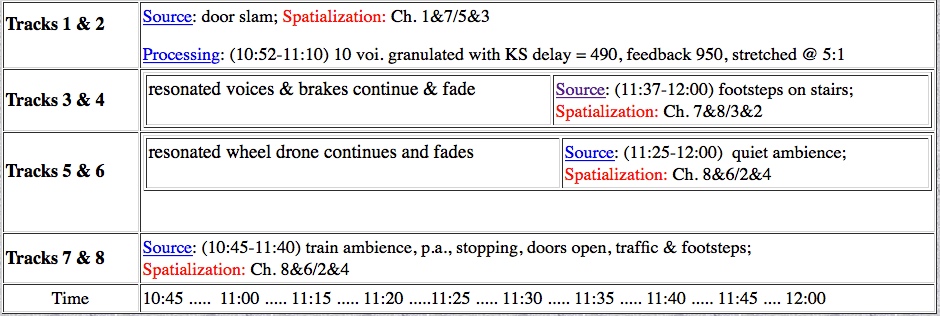

shown below as the Source for tracks 3&4 and 5&6. Each

loop is resonated at two different pitches (for the left and

right channels), and gradually the feedback is raised until it

becomes a resonant drone. Note that the percussive rhythm in

the second loop keeps its rhythm going.

Tracks 1&2 use a filtered version of the high frequency

brake sound that is time-stretched and resonated as well. The

mix of all three stereo tracks creates a smooth daydream

effect, but also notice that tracks 7&8 have a

untransformed engine sound that keeps us grounded in the

realistic soundscape already created.

First

passing train loop

Second

percussive train loop

|

Production

score of first daydream in Pendlerdrøm (1996):

click to enlarge

|

First

daydream sequence in Pendlerdrøm (1996)

from Islands, CSR-CD 0101

|

Click

to enlarge

|

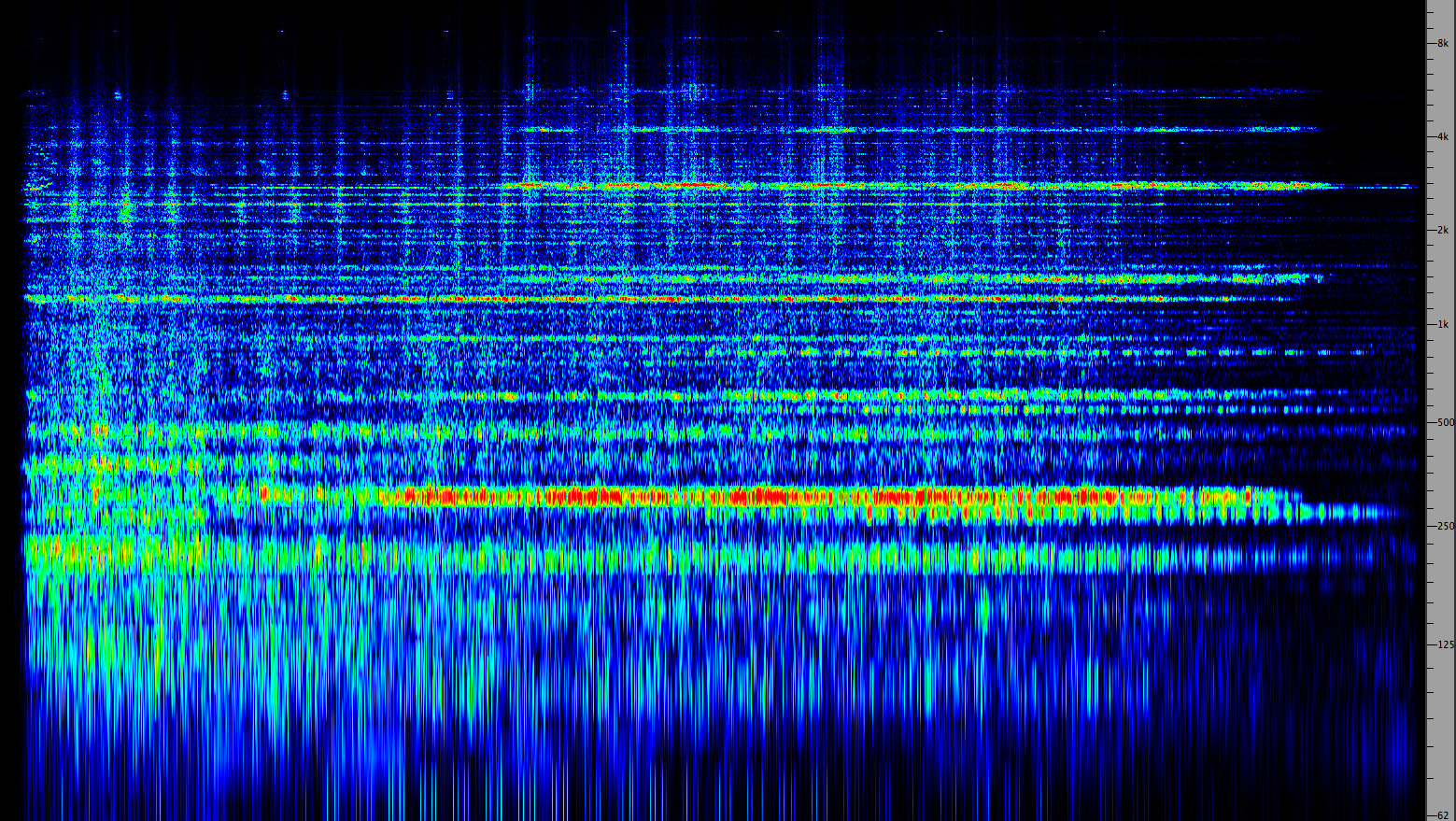

The

second daydream section in the piece, once we’ve settled down

on the smaller commuter train, is handled similarly, with two

stereo tracks being resonated, including a percussive wheel

drone, and the sound of brakes an octave lower, resonated and

stretched. The transition into the daydream is faster (I guess

our commuter is really tired at the end of the day) and a

random collage of short bits of sound from earlier in the

piece (mainly voices and signals) come back in short loops

that are repeated and resonated, a little like flashbacks or

“earworms” that go through one’s mind during relaxation.

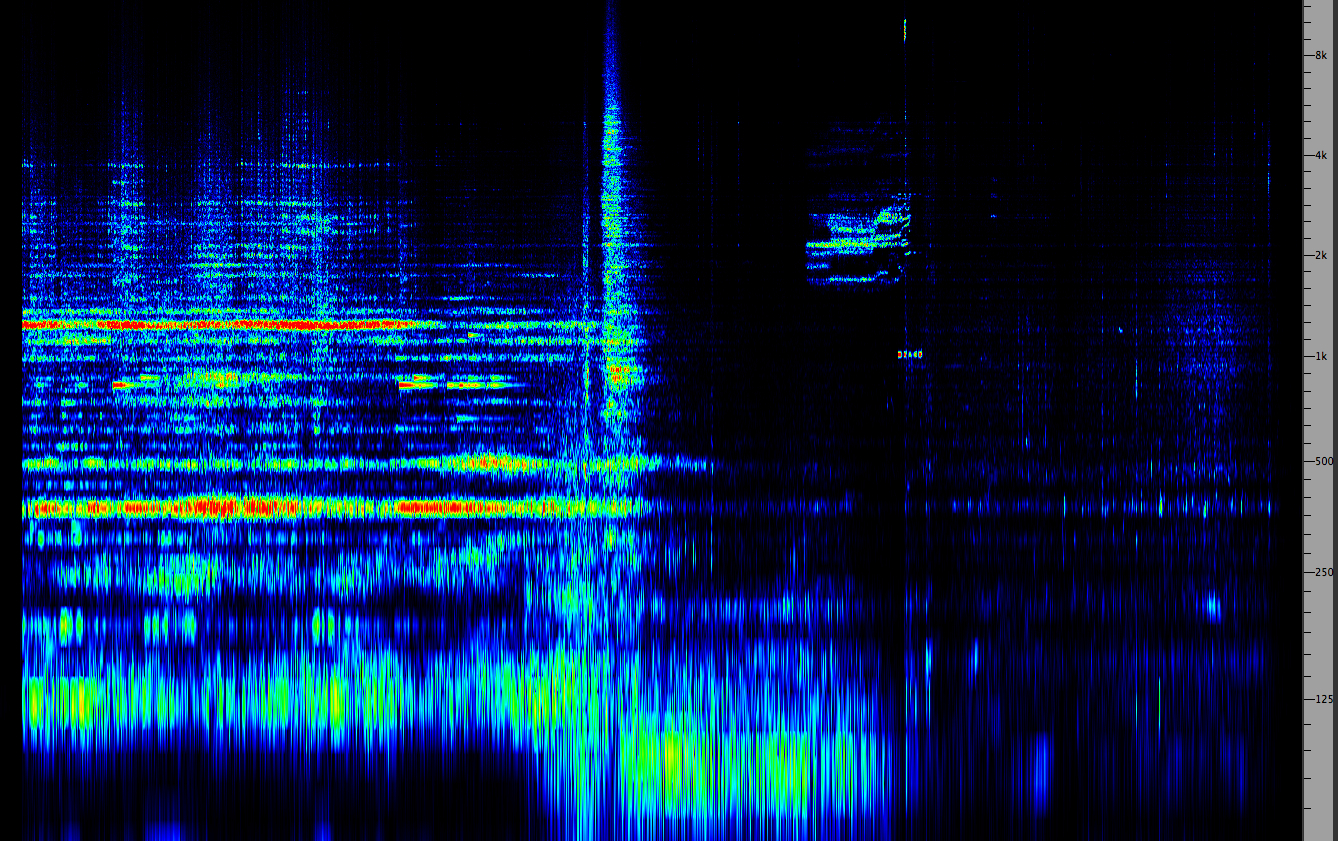

So, the final challenge is how to get out of this daydream. In

this example, we hear the end of the drone sequence where even

the resonated soundbytes are fading into the overall texture,

and then as the train slows down we hear a station being

announced, and there is a huge percussive chord as our

commuter suddenly wakes up with a start.

In fact, this sound is derived from a simple door slam on the

train itself that was heard earlier from another train where

passengers were getting off, but it has been significantly

enhanced with a resonator and a 5:1 granulated stretch factor.

We then hear the door signal as it opens, our commuter gets

off and walks down a wooden staircase into the outdoors and

the piece ends with what sounds like a cigarette or pipe being

lit.

Train

door slam (original source)

|

Production score for the ending of Pendlerdrøm

(1996): click to enlarge

|

Ending

of Pendlerdrøm (1996)

from Islands, CSR-CD 0101

|

Click

to

enlarge

|

Because the original sound material was recorded around 6pm,

the scenario of the commuter going from Central Station to

home seemed a natural choice. However, for reasons only known

to the Danish recordist, he actually recorded it in the other

direction, going from the suburbs to downtown, so the

sequences from his recordings had to be re-ordered to go in

the other direction, and so far no one has noticed or

objected.

The final example in this section is from

Anne Holmes’ Wood on Wood on Water (1978), a

quadraphonic piece with a coastal soundscape. The journey in

this case is not a physical one, but is a bit opposite to the

daydream in Pendlerdrøm, namely a transition into a

high attention state where all of the background noises fade

away.

The featured sound is a series of simple hits on a beached

log, which is quite resonant on its own, but then a virtuosic

percussion performance emerges (created with tape delays,

although it could be mistaken for an actual percussion

ensemble). The dynamic sounds move into the foreground and are

so engrossing, we’re not likely to hear that the tide is

gradually coming in (a common experience at a tidal beach).

A

beached log improv from Anne Holmes’ Wood on

Wood on Water (1978)

from SFU-40, CSR-CD 0501

|

Click

to enlarge

|

In the

section following this excerpt, even the seagull cries

disappear, until finally at the end of the concert, there is a

sudden surge of the tidal waves as we realize what has

happened to the tide in the meantime. Gradually towards the

end, water engulfs the log and it loses more and more of its

high frequencies and resonance, until it is finally submerged,

showing that wood and water are opposites in many senses.

Eventually the seagulls return (also to our awareness) and the

piece ends.

Other examples of a moving perspective will be presented in

the final section.

Index

D. Abstracted spatial perspective.

Here we will group together a variety of approaches to

soundscape composition that do not fall simply into a fixed

or moving perspective model. To use similar terms, we could

say that they exhibit discontinuous space/time

flows. However, to put it more positively, we could also say

that they present their material from multiple perspectives,

or in an abstracted, even symbolic manner.

However, keep in mind that in the electroacoustic era where

we daily hear a mix of acoustic and electroacoustic sounds,

it has become customary to hear technological sounds embedded

in the everyday soundscape. Murray Schafer referred to this

phenomenon as schizophonic

to emphasize the split between the source and its reproduced

form, and occasionally the “fit” still has a disruptive or

“nervous” quality about it. However, we usually adapt

quickly and normalize the presence of such embedded sounds,

even as we understand that they are in the

environment, but not of it.

The first example is a simple montage

(i.e. edited) string of Vancouver sound signals, that was

called (for better or worse) “The Music of Horns and

Whistles” when it appeared on the Vancouver Soundscape

1973 vinyl recording. The fact that all of the sounds

are pitched made it easy in those days to refer to them as

musical, and the track itself was often the one selected by

others to showcase the WSP work.

Excerpt from The Music of Horns and

Whistles

from The Vancouver Soundscape (1973),

CSR-2CD 9701

|

Click to enlarge

|

In the current context, there is simply a common theme to

the track – all of the sounds you hear, along with an

appropriate ambience, are typical Vancouver signals as a

port city, the end of the transcontinental railway line,

with an industrial harbour and mountains on one shore which

adds a natural reverberation to many of these sounds. This

excerpt is the last minute of the 3-minute track.

Next we have my Pacific Fanfare (1996),

an anniversary tribute to the WSP that begins with a 30”

montage of Vancouver soundmarks, the Pt. Atkinson diaphone

heard earlier in this module, the 9 O’clock Gun in Stanley

park, the Royal Hudson steam train whistle, the B.C. Ferry

horns at Horseshoe Bay, and the Holy Rosary Cathedral bells.

Immediately following this opening, we hear many of these

sounds time-stretched (as documented in the Microsound module) and

resonated. Compared with the simple identification of each

sound at the beginning, we now have a more reflective

listening experience of hearing “inside” them as their

evolution plays out. There are also new soundmarks

introduced such as the light rapid transit Skytrain (with a

bit of sly humour when the characteristic starting motor

sound is slowed down). The piece ends with the O Canada

horn, sounding at noon downtown, and in the distance, the

transcontinental Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) train

whistle in the distance, a reference to its historic role in

uniting the country east to west.

Pacific Fanfare (1996)

from The Vancouver Soundscape (1973),

CSR-2CD 9701 and Islands CSR-CD 0101

|

Click to enlarge

|

Next we present two movements of Canadian

composer Claude Schryer’s Vancouver Soundscape Revisited

(1996) who refers to the piece as “an impressionistic

portrait of the musicality and poetry of the soundscape of

Vancouver”. In terms of this presentation, it is also a good

example of an abstracted perspective on the soundscape of

the city, based on the WSP’s recordings which were collected

in the 1970s and 1990s.

The second movement of the piece, Fire, seems like a

stream of consciousness in its often surprising

juxtapositions of the city’s sounds. However, it is not at

all random. Schryer catalogued the sounds he chose from the

WSP collection in terms of spectrum, category, function,

pitch and context, and in this movement he linked the sounds

together according to one or more of these aspects they had

in common.

He made only small modifications in terms of level or pitch

to facilitate smooth transitions, one exception being the

downward transposition of the foghorn at the very end. Fire

being notoriously volatile, that metaphor allows quite free

associations with the energy of these sounds, dynamic at the

beginning, slowly subsiding to some final embers at the end.

The fourth movement is called Noise and begins and

ends with a complaint about that kind of disruption,

followed by a more literal series of examples.

Claude

Schryer's "Fire" movement, Vancouver Soundscape

Revisited (1996)

from Soundscape Vancouver 1996, CSR 2CD-9701

|

Click

to enlarge

|

Claude

Schryer's "Noise" movement, Vancouver Soundscape

Revisited (1996)

from Soundscape Vancouver 1996, CSR 2CD-9701

|

|

A final example in this section is from the

German composer Hans Ulrich Werner who has specialized in

radiophonic work, including Vanscape Motion (1996),

which like the Schryer work, was composed for the Soundscape

Vancouver project and double CD in 1996.

In this excerpt from the piece, the spatial perspective is

abstracted by reversing their more usual presentation.

We hear the sequence of foreground signals used in The

Music of Horns and Whistles from the 1973 Vancouver

Soundscape publication, but they are in the background, and

act as a kind of memory, perhaps emphasizing their historical

nature. In the foreground is a sequence of reverberated waves

and water splashes that place them in a different space

altogether, one of intimacy and repose. This technique of

having two different acoustic spaces with highly contrasting

affect seems to facilitate reflective listening.

Excerpt

of Hans Ulrich Werner's Vanscape Motion (1996)

from Soundscape Vancouver 1996, CSR

2CD-9701

|

Click to enlarge

|

Index

E. Detailed analysis of specific

soundscape compositions. Here we will present a more

detailed analysis of some specific pieces by Hildegard

Westerkamp and Barry Truax. Although published on CDs in

stereo, these pieces are usually performed in 8-channel

format which provides an immersive effect for the listener

which in some cases simulates an actual acoustic space or an

abstracted version of it that creates a virtual soundscape.

Hildegard’s work Into the Labyrinth (2000) is one of

several pieces composed in the context of visits she made to

India which included workshops and soundwalks with people

there. She describes the work as a “sonic journey into

aspects of India’s culture. It occurs on the edge between

dream and reality, in the same way in which many visitors,

myself included, experience this country.” The piece has

been published on the Earsay CD, Into India.

It clearly falls into our above category as an abstracted

soundscape where highly realistic environmental sounds

are combined with their transformations. She has generously

documented several of these transformations which are

presented in this sidebar.

They follow the tradition of sound object transformation,

including pitch transpositions, equalization and mixing

variants into more complex sound clusters, similar to the

studio demonstrations used throughout the Tutorial.

In these examples, notice how exploratory they are,

and how at certain key points, a feature will emerge that

obviously caught her ear, and subsequently was utilized in

the next stage of the process, such as the resonance heard

on one of the strikes in the stone chipping recording from

Rajasthan, once it was transposed down 8 semitones and then

an octave which stretched it further.

The examples also reveal some practical details about how to

separate a sound, such as the bicycle bell from Delhi,

recorded on a busy street, from its noisy ambience into a

more useful form. It eventually becomes both a resonant

drone when stretched and pitch shifted by 6 octaves, as well

as a cloud of bells when different pitch shifts are combined

and transposed.

The extremely high pitched “singing crickets” from Goa, as a

whole and in two isolated recordings, also create rich

textures when transposed to which Hildegard has added reverb

that gives them a unique acoustic space, as in the sidebar.

Here we present a stereo mix of the opening of the piece

which evocatively introduces the Indian soundscape in a

series of overlapping vignettes that seamlessly mix the

realistic sounds with the processed ones, or as she puts it,

places them “on the edge between dream and reality.”

Opening of Hildegard Westerkamp’s

work Into the Labyrinth (2000)

from Into India, Earsay CD

|

Click to enlarge

|

Hybrid Convolution. In other

modules, we have covered the basic theory and practice of

convolution via Impulse

Reverberation and Auto-convolution.

The special case of auto-convolution where the sound is

convolved with itself leads to the question as to what will

happen when we convolve two different sounds together.

Since convolution involves a multiplication of the

frequencies which the two sounds have in common, our first

expectation is that it will be worthwhile to pursue this

hybridization only when there is significant overlap

between the spectra of the two sounds. High

frequencies convolved with low simply won’t produce very

much, if at all.

It was with a curiosity to find out the answer to this

question that I embarked on experiments in 2009 with what

I’m calling hybrid convolution. Even the first

results were so inspiring that within an amazingly short

period of time I was able to create an 8-channel work called

Chalice Well (2009) and premiere it at the Sonic Arts

Research Centre’s Sonic Lab in Belfast on a 32-channel

speaker rig which gave it the added height that was needed.

Previous casual experience showed that if you combine two

broadband sounds together, you only get an undifferentiated

wash of sound that isn’t useful for much other than an

ambient track. So, why did these initial experiments

succeed? First, the materials used were environmental

recordings, mainly of watery sounds, but also glass

breaking, bubbles in water, sharp percussive sounds of locks

and doors, and some gated and transposed male phonemes.

These were convolved with themselves, and two other types of

sounds, a female vocal text, and four examples of sine-wave

granular synthesis.

The key element to the success of the experiments was that

all of these sounds were “pointillistic” in a sense, that

is, with micro attacks in their textures, including

a few major percussive events, such as a water splash. This

characteristic gave the convolved sounds a similar, extended

texture that seemed to be a hybrid version of the two

component sounds.

The second element that was suggestive of a possible

soundscape was that some of the watery sounds (recorded by

David Monacchi in Italy) were deep in a well that had its

own resonant properties. When extended, these sounds had a

reverberant quality. So, if we categorize the source sounds

as dry or wet (no pun intended), we get the following

spatial result when they are convolved with each other:

Dry with dry produces a foreground sound

Dry with wet produces a middle ground sound

Wet with wet produces a more distant sound

There is a full documentation of all of the sounds used in

the WSP Database, but since there were more than 200 hybrids

produced, we can’t include them all here. Instead, we will

put a selection of them in a sidebar.

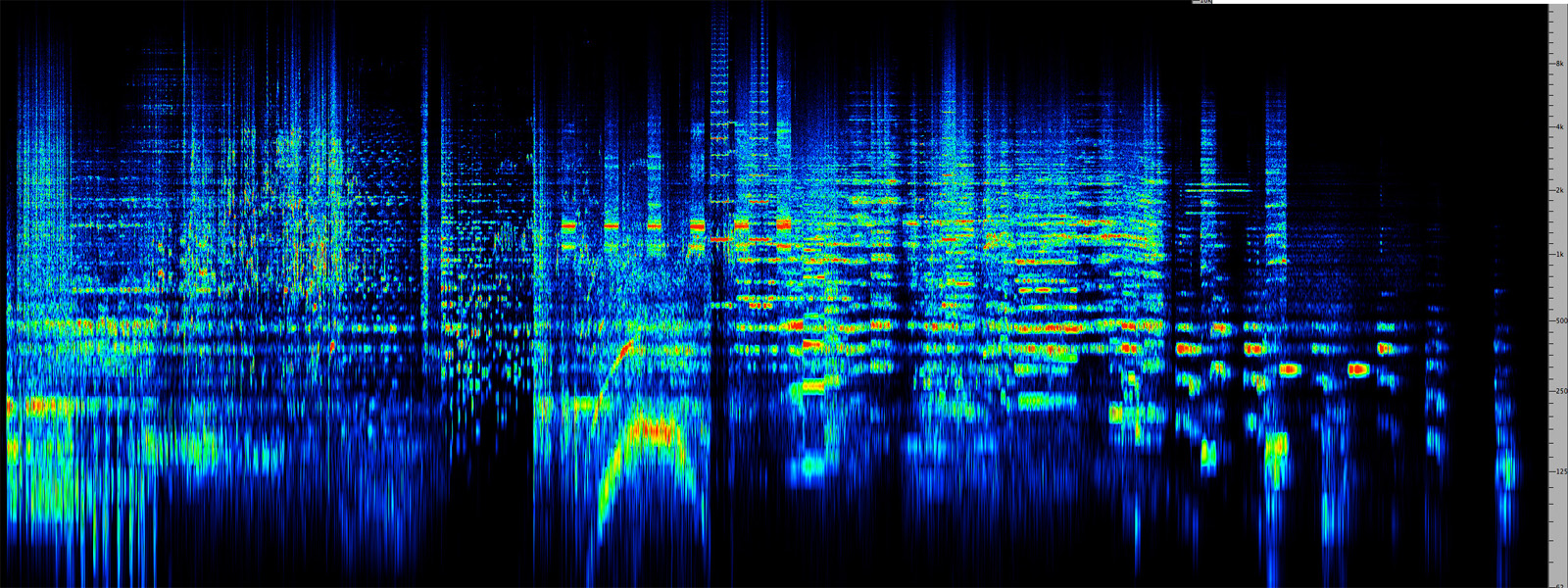

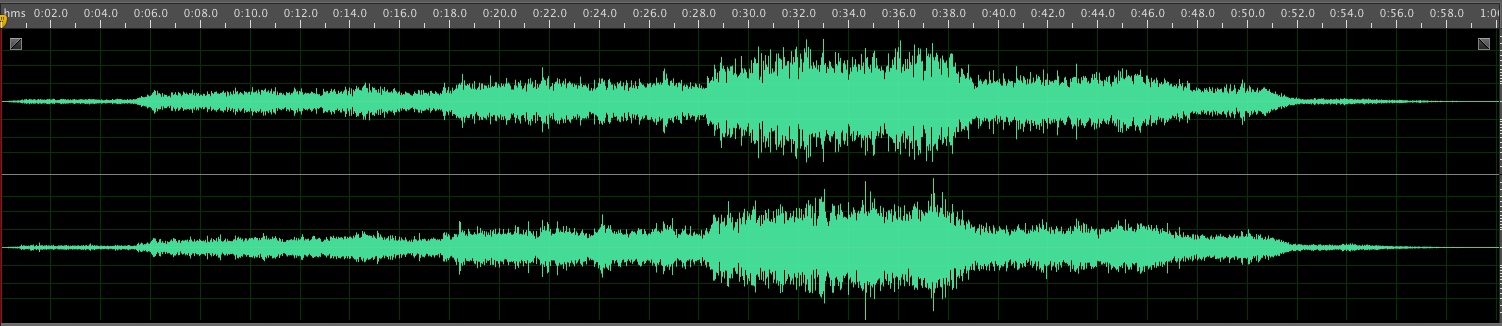

A third variable that came out of the

experiment and was particularly valuable for creating an

8-channel space was the discovery that file A convolved with

B was not the same as file B convolved with A, as

some texts might imply. After a quick consult with Tom Erbe,

the creator of SoundHack, the reason became known.

Convolution will be symmetrical (A*B is the same as

B*A) but only when the analysis window is

rectangular, that is, no slope to the window. The analysis

windows I was using were typically the Hamming variety which

has slopes on either end. So, even though the results of A*B

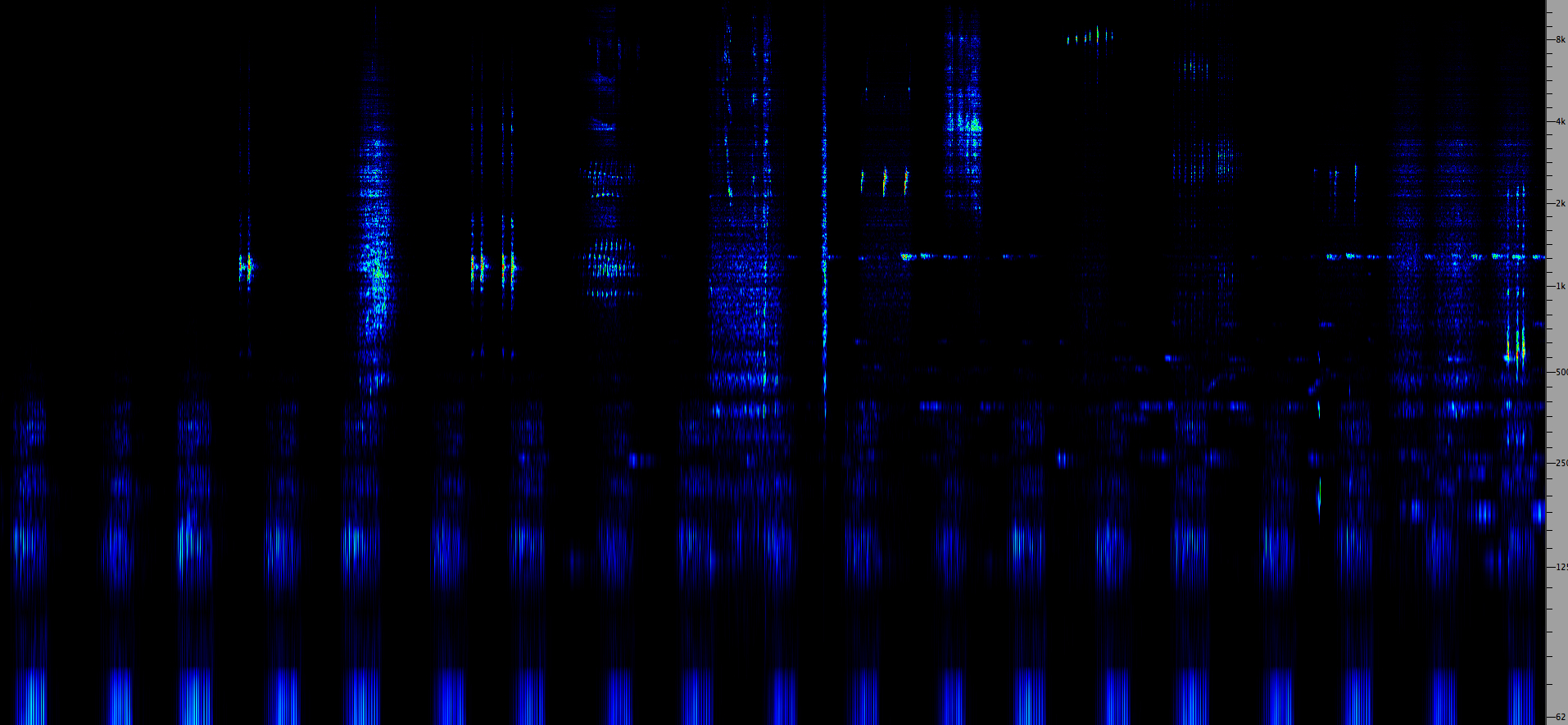

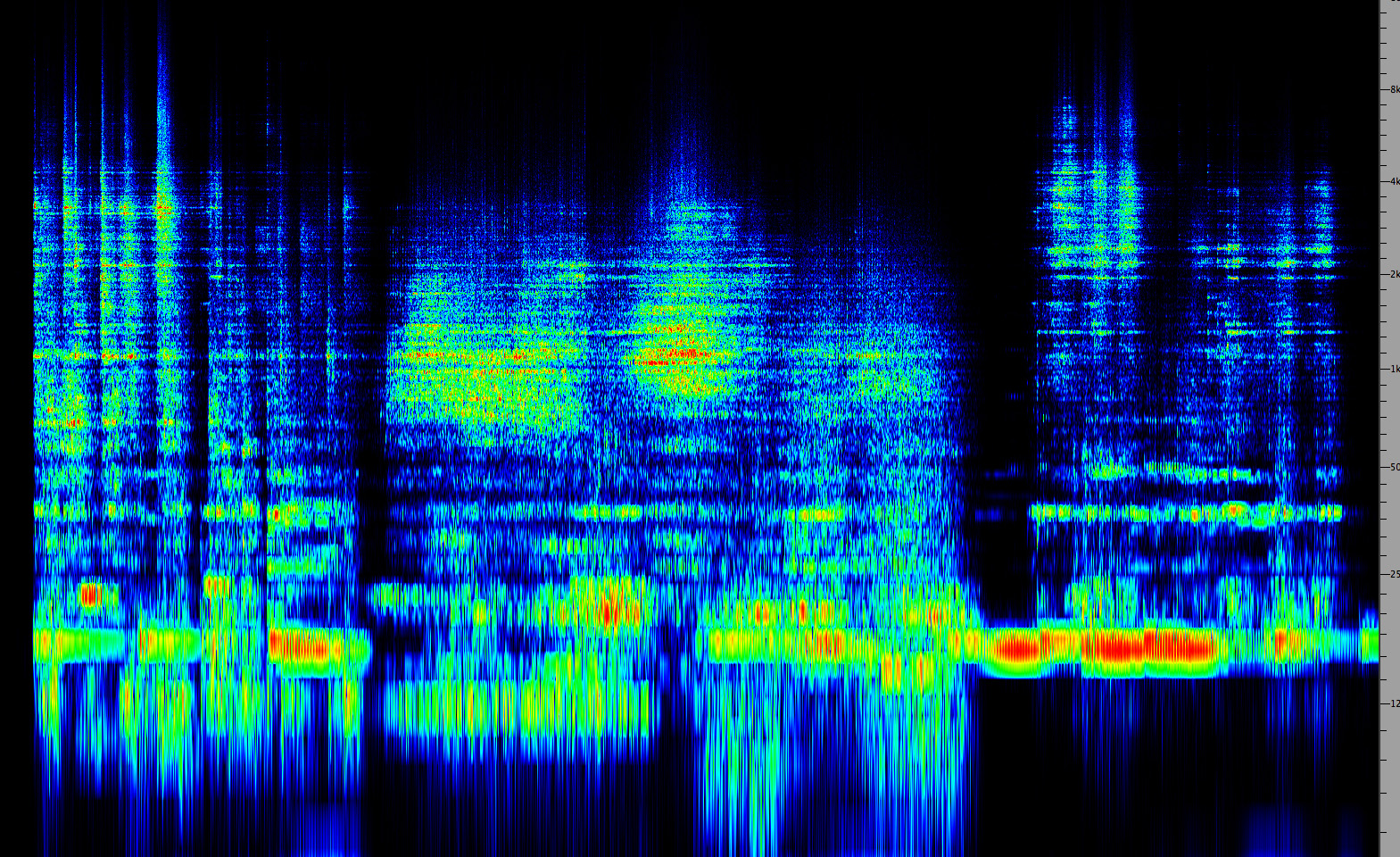

and B*A were similar in terms of their spectra and texture,

their global amplitude envelopes were quite different as

shown below.

This proved to be useful because more variants could be

generated to fill up the 8-channel space. The differences in

amplitude envelopes provided an extra spatial dimension for

the sound to seem to move around the space. It is quite

interesting to consider that this difference at the micro

analysis level could make such a larger difference at the

macro time scale – yet another instance of the nature of the

microsound domain.

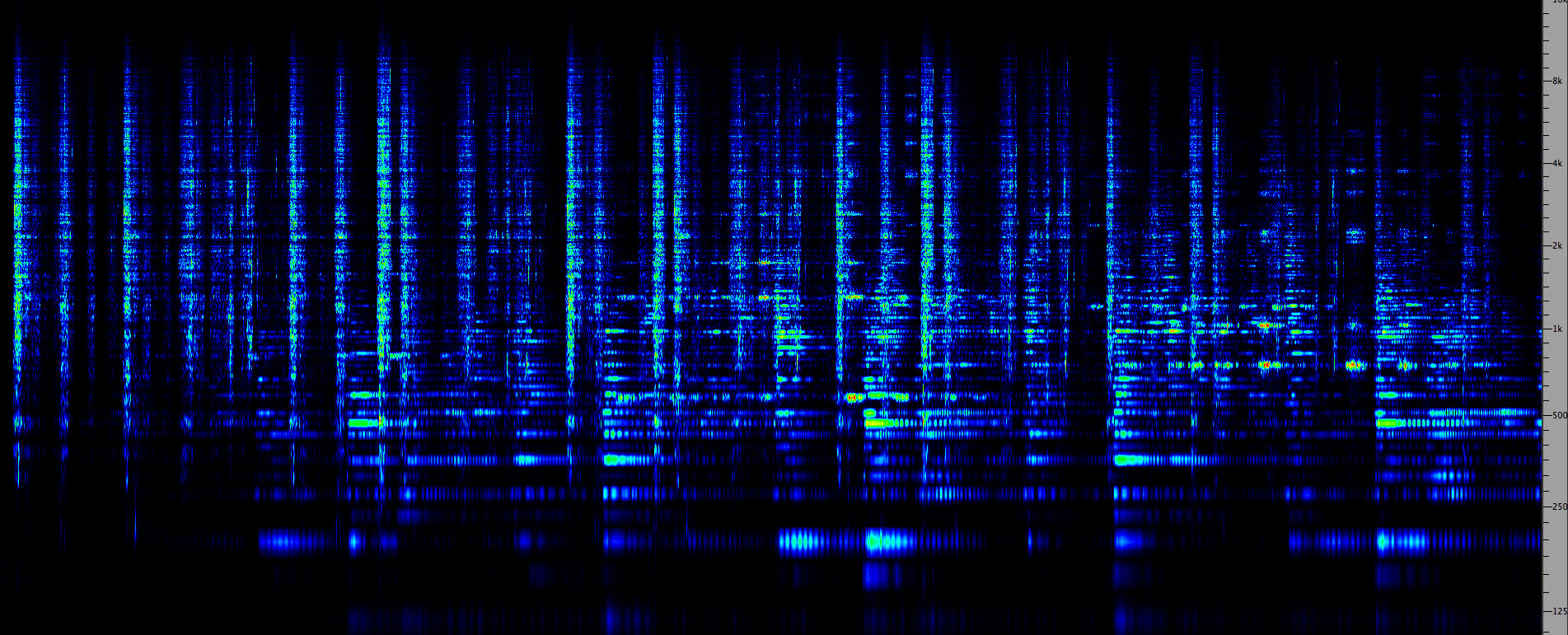

Water*Well

|

Well*Water

(click to enlarge)

|

As to the macro compositional level

of the piece, the image of a well came to mind early on

because of the Italian source material, and my experience in

visiting Chalice Well at Glastonbury in the south-west of

England, a holy site steeped in legends and myths. Wells

sometimes have a certain aura about them, as this one did,

despite the fact that, being covered, there was little in

the way of sound to be heard.

However, in reading about the many myths associated with the

Well, the one that made an impression was the legend that

underground caverns exist below it, and that this is where

Joseph of Arimathea buried the chalice known as the Holy

Grail, in order to protect us from evil. These caverns have

never been discovered, and historians are quick to point out

that many legends were in fact created by the monks in the

Middle Ages to boost tourism (some things never change!).

But, in the case of soundscape composition, we are not

dependent on referring to actual space, and the sounds I was

generating with hybrid convolution suggested an imaginary

virtual soundscape, and a soundwalk type of moving

perspective through it.

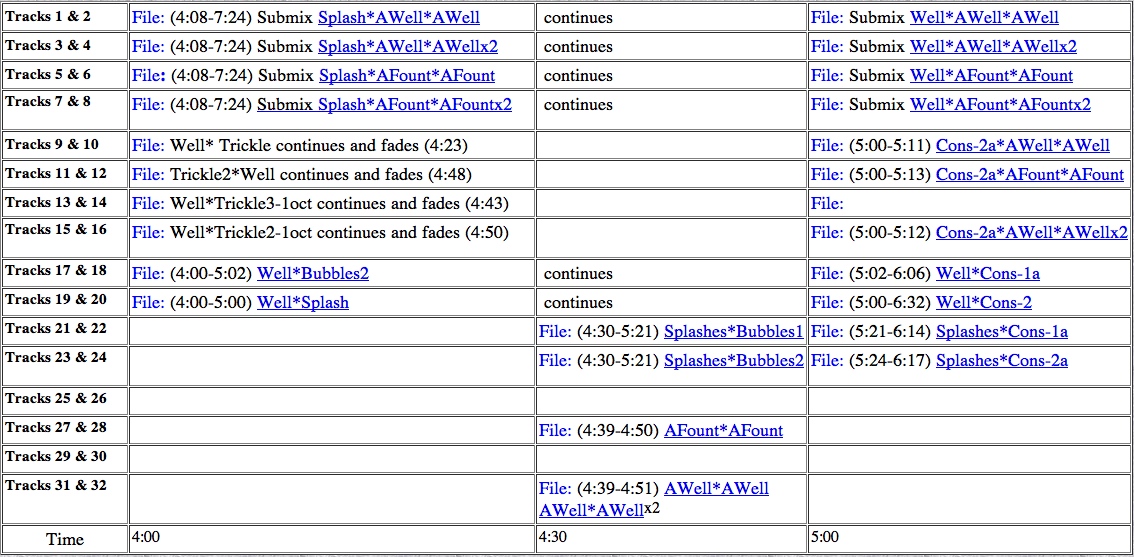

Here are two excerpts in stereo reduction from the piece,

the first starting at the 4’ mark for a scene I call The

Chamber of the Feminine. The name refers to the historical

gendering of the well as feminine, and some of the source

material included a female voice reading from the Song

of Songs about a well (not that you’re going to

understand any words but the files referred to below are

identified as "AWell" and "AFount"). When convolved with

other sounds, the female formants come through and seem

blurred and sustained enough to be symbolic.

Production score of Chalice Well, Chamber of the

Feminine

Excerpt

of Chalice Well (2009)

Chamber of the Feminine

starting at 4'

from The Elements and Beyond, CSR-CD 1401

|

Click

to enlarge

|

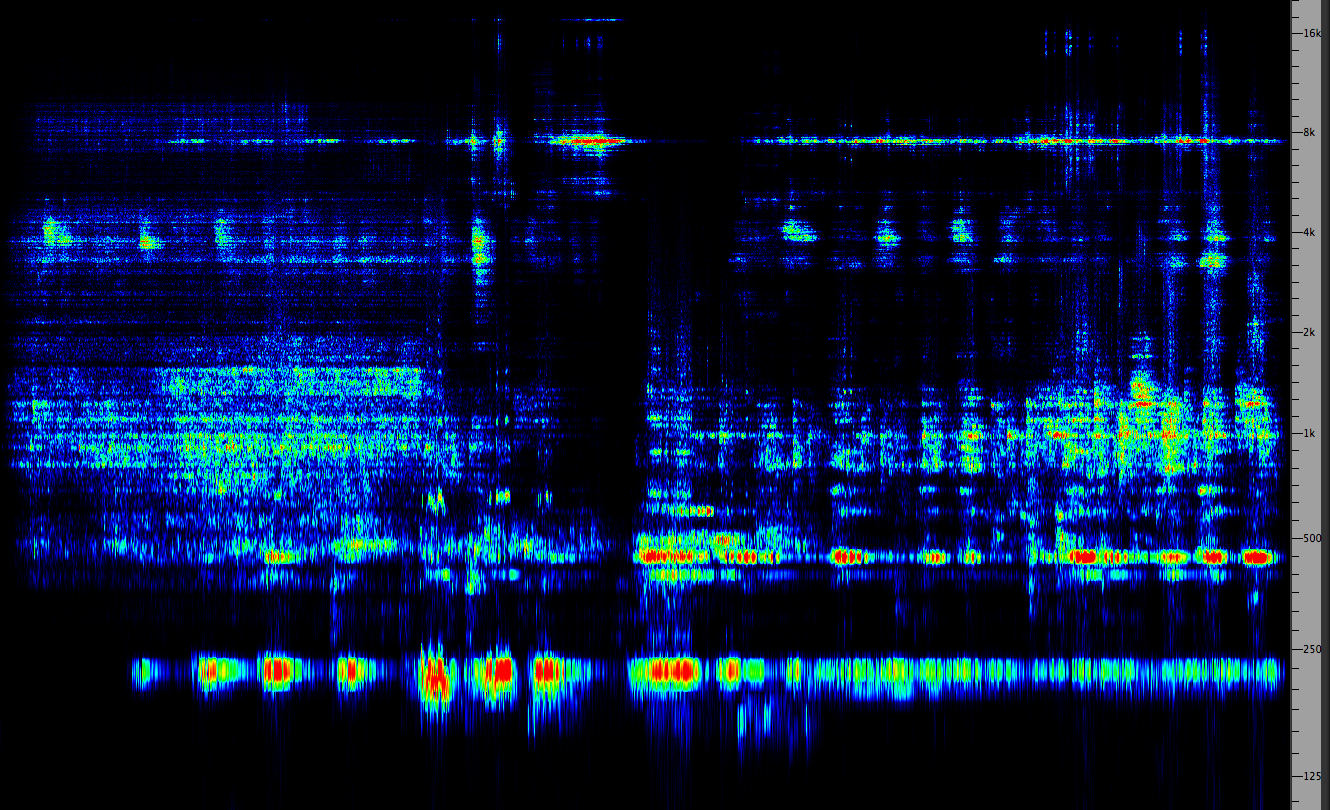

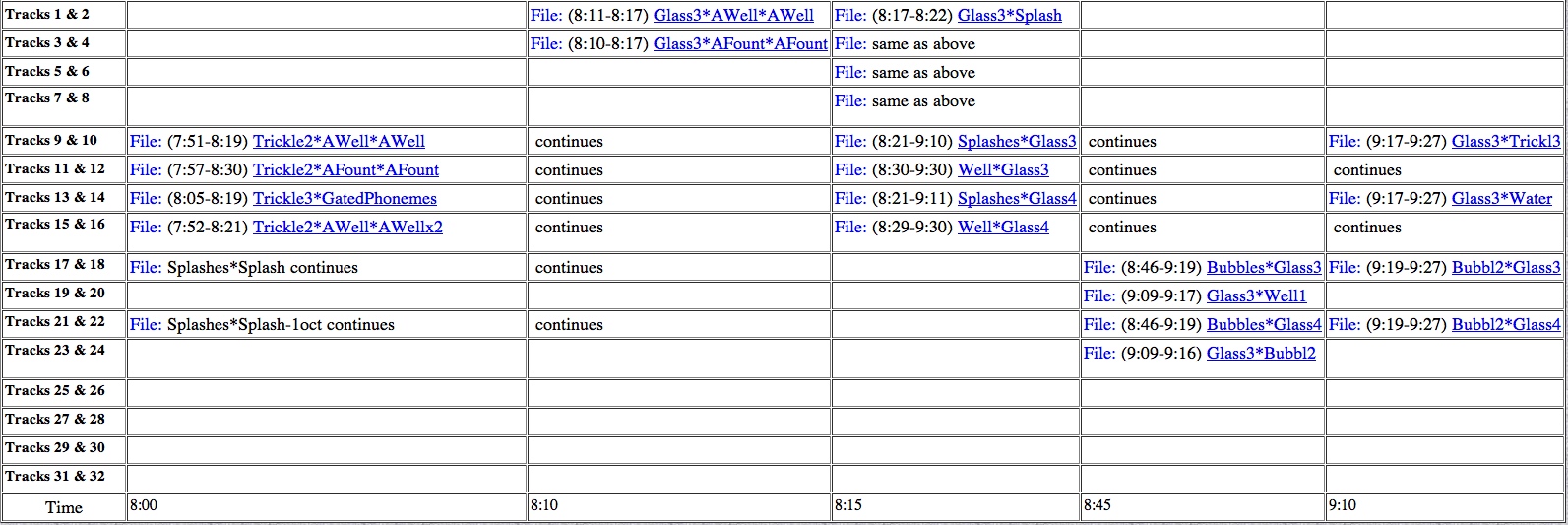

The second

excerpt is from the end of that scene with the transition to

the Glass Chamber, named because of the glass elements used

in several hybrid convolutions of glass with other sounds,

and at the end of the excerpt we are at the entrance to the

underworld.

Production

score

of Chalice Well, Glass Chamber; click to

enlarge

Excerpt of Chalice Well (2009)

Glass Chamber

starting just before 8'

from The Elements and Beyond, CSR-CD

1401

|

Click to enlarge

|

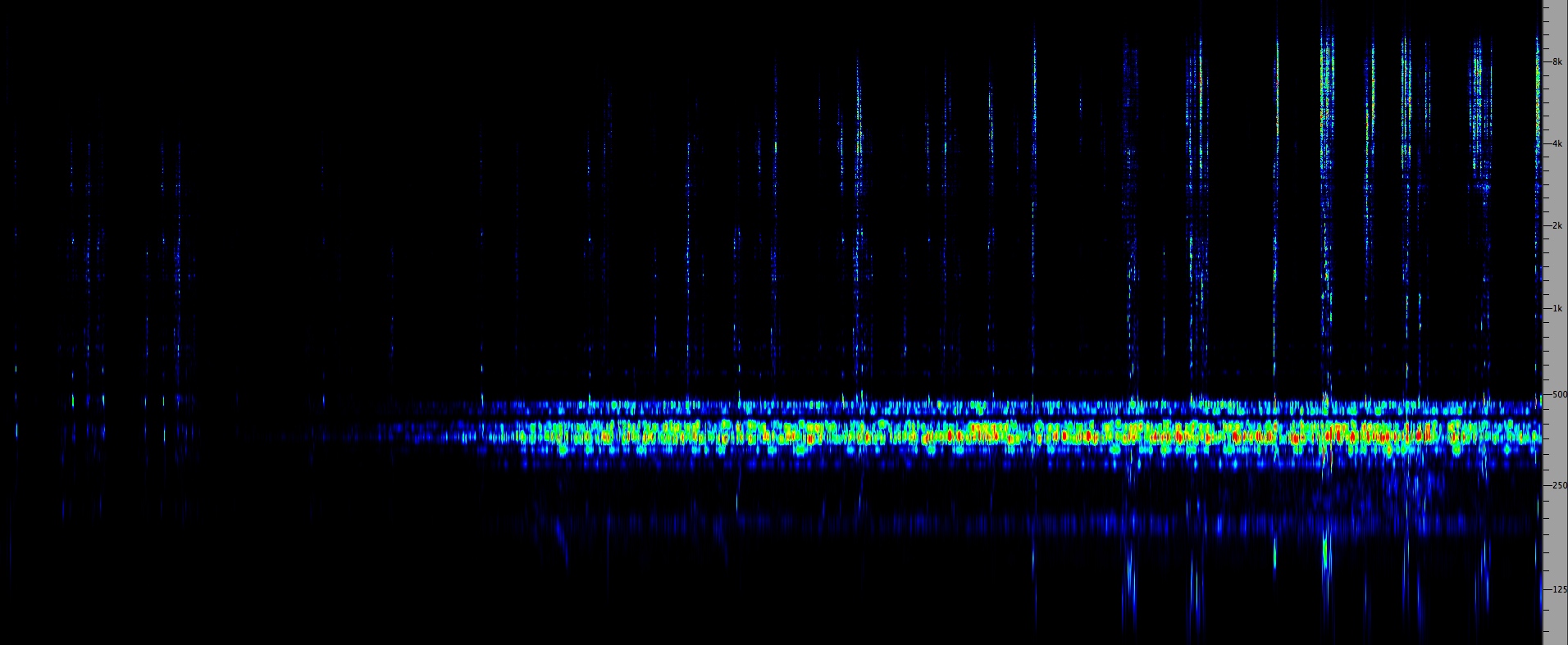

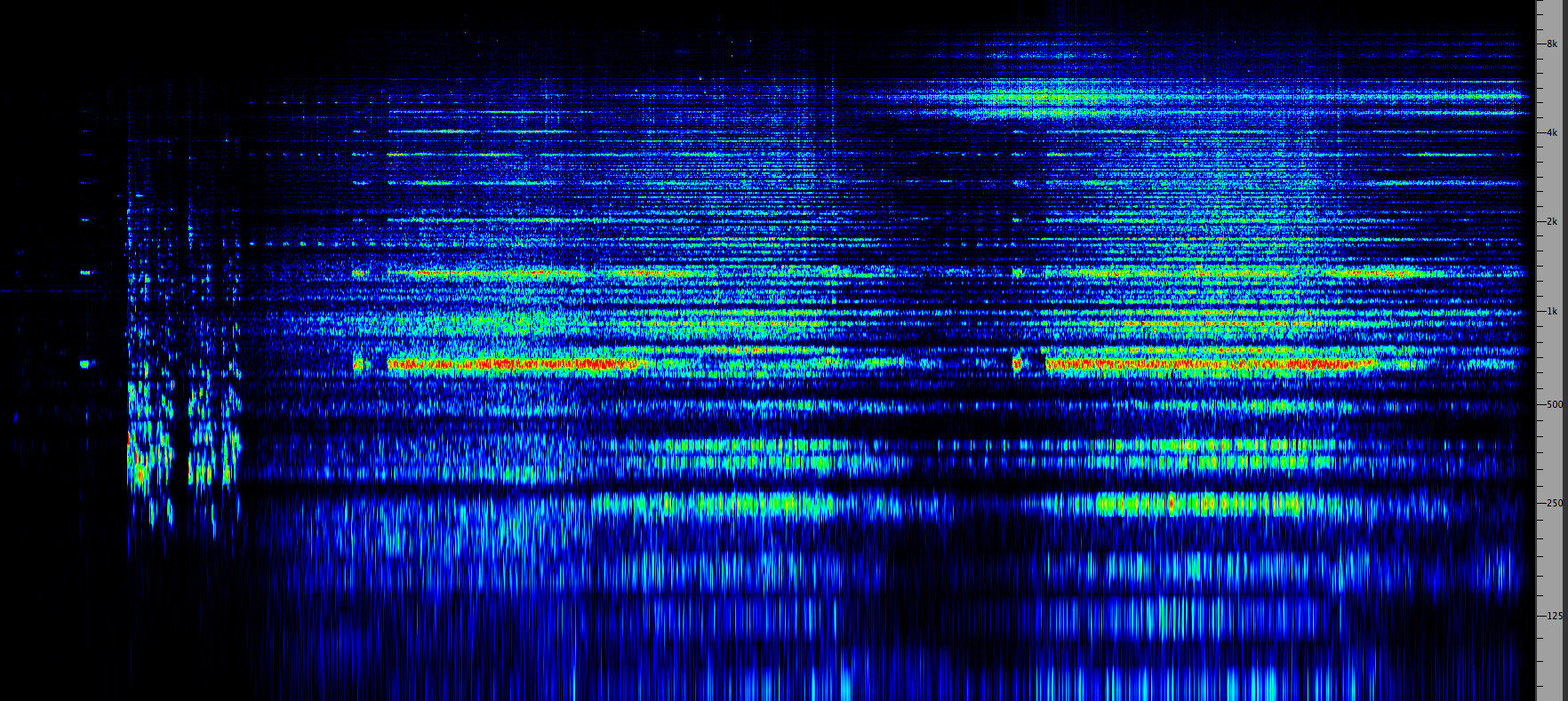

Extended complexity in hybrid

convolutions. My 2019 work Infinity Room

tries to take hybrid convolution a step further towards

a more abstracted perspective. The only analogy I could

think of (after the materials were already

developed) was the visual complexity and sense of

boundless space in an “Infinity Room” installation,

which has made them very popular in art galleries, but

what could we imagine would be the aural equivalent?

The resulting work creates a somewhat analogous

experience in an immersive space where a large number of

environmental sounds are refracted (i.e. convolved) with

each other and move around the listener until they trail

off into the distance. Percussive, as well as musical,

vocal and noisy sounds from various cultural sources,

combine in seemingly endless variations as we move from

mirrored room to room.

Technically, the work is based on a set of 27

acoustically rich environmental samples, each of which

is convolved with all others to create 351 stereo

hybrids (where the L/R channels are A*B and B*A). The

samples range from impulse responses in large spaces

through percussive sounds, musical and vocal excerpts,

bells, thunder and strange noises.

Each of the 351 hybridized sounds is spatialized

independently, often in trajectories around the listener

in the multi-channel space incorporating echo delays. It

is hard to imagine that any other soundscape-inspired

work has embodied this much complexity.

Just to give an impression with a stereo reduction of

this multi-channel work, here is an excerpt of three

“rooms” (or sections) of the piece, the first being a

variety of percussive sounds convolved with each other.

This is followed by a section based on a clapping sound

convolved with many other sounds, spatialized as shown

below, followed by a short clip of a traditional Korean

band convolved with various impulse responses from other

spaces.

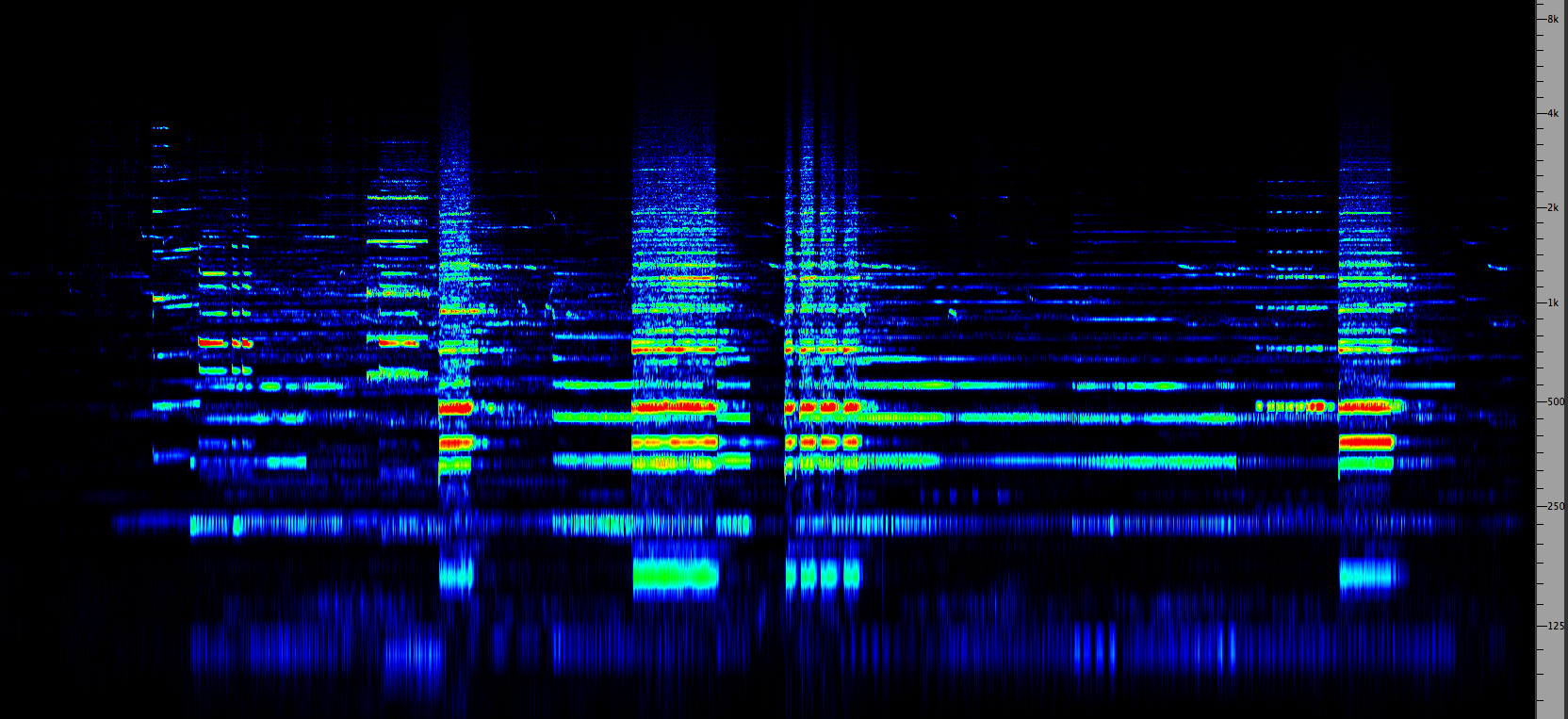

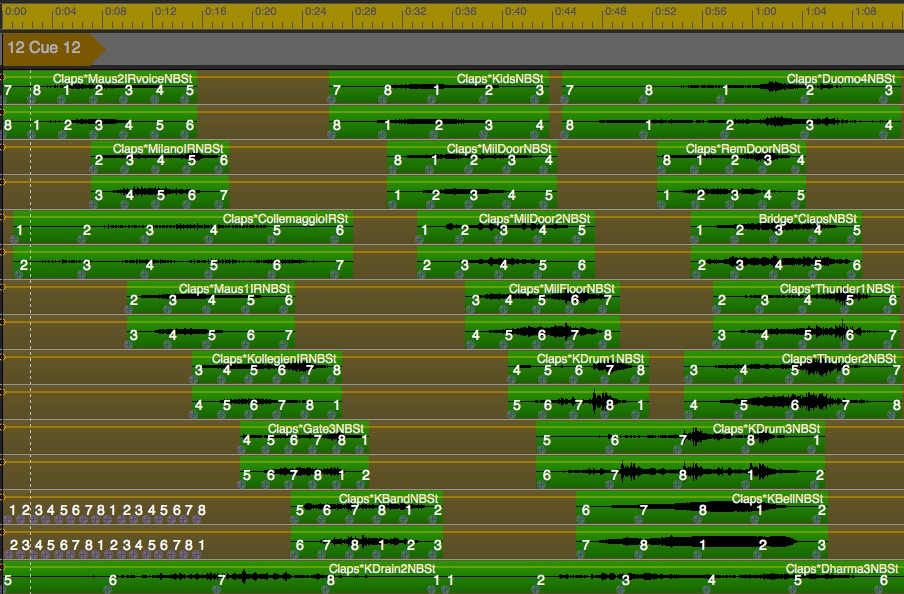

Cue from the 3rd section of Infinity Room (2019)

with 8 stereo tracks of convolved sounds; the numbers

indicate the loudspeakers in the trajectory of each sound

in the TiMax2 Soundhub spatialization software

Excerpt

of Infinity Room (2019)

|

Click

to enlarge

|

home