Introduction (toc)

The motivation behind

creating a mediated pedagogical design for instructing video production comes

from my experience as a media production teacher. I have taught novice videographers[1]

who aspire to produce a great range of video productions, from better home

movies, to politically active segments, to feature length documentaries. This

range of aspirations creates difficulties for a pedagogical design including

how an instructional system can be relevant to individuals with diverse

learning requirements. I also see

a need for a system of instruction in video production that can be used in

various independent production environments, such as non-profit communities,

Independent Media Centres, public schools, community based programs, and other

groups whoÕs access to resources are limited by social, economic, or geographic

barriers. My intention for this mediated pedagogical design is that it can be a

system that can provide an alternative to strictly preparing learners to work

in the "winner-take-all" environment (Geuens, 2000) of the contemporary culture

industry.

The problem then is to

design a system of instructional resources for video production that can be

useful across a range of user levels as well as being affordable and accessible

to independent videographers. In an attempt to address this problem I am

suggesting a mediated pedagogical design for video production that is based on

cycles of iterations and delivered via the common media presentation

environment of a web browser. This mediated pedagogical design is intended to

be a resource for teaching video production on as general a level as possible

(i.e. not genre based, not specific to a particular video product) and to be

used across a range of educational and independent production environments.

The outcome of my

attempts to create a mediated pedagogical design to teach video production is

the Cycles of Iteration web site (www.sfu.ca/media-lab/cycle or see

accompanying CD-ROM). This site

includes three iterations of the production process which are each divided into

four quadrants namely: Pre-production, Production, Post-Production and Review.

The three cycles of iteration are designed to take a novice videographer from a

level of virtually no production knowledge to the point of producing a short,

self-contained, and presentable video production. Although there is a desire to

have a totally autonomous, self-directed pedagogical system, the complexities

and subtleties of video production have resulted in this design being a hybrid

that combines synchronous presentation materials with asynchronous review and

reference information. As a result the Cycles of Iteration interface is has

dual functions: As an instructor or facilitator lead teaching resource, and as

a reference site for learners.

Problem Statement

The problem that I have

tried to address in the design of the Cycles of Iteration interface is how to

consolidate and organize the large volume of knowledge that is needed in order

to take a novice videographer to the point of producing a finished video

product.

User Profile

The Cycles of Iteration

interface was designed to accommodate novice videographers and take them from

never touching a video camera to the production of a short video. There is no

specific age group for the user profile, but the need or desire to communicate

through the production of video is assumed (See the scenario building section

for examples of users).

Context

The design of the

Cycles of Iteration interface was created with an intention to apply theories

of critical pedagogy that investigate the relationship between experience,

action, and knowledge within a practical design context. The pedagogical

theories formed a foundation that drew attention to the process through which

knowledge can be created (Lusted, 1986). The process of knowledge creation

became important to the design method because it formed the observable (pilot

study) and imaginable (scenario building) data.

Developing the Cycles

of Iteration interface was also an examination of the way technology mediates our

methods of knowledge transfer in contemporary learning environments. The

browser-based interface represents a form of informational mediation that is

very much part of present-day education culture.

Theoretical Framework (toc)

The term mediated

pedagogical design represents the three theoretical traditions that were drawn

upon during the creation of the Cycles of Iteration interface.

á

Media

Literacy

á

Critical

Pedagogy

á

Design Theory

Media Literacy (toc)

Media Literacy is a

term with many definitions. In the most general sense it refers to the

development of knowledge of or training in the field of mass media (Television,

print, video, Internet, new-media, etc.). A more expanded definition that

raises issues of social responsibility is given by the Center for Media Literacy:

"Media Literacy is a 21st century approach to education. It provides a framework to access, analyze, evaluate and create messages in a variety of forms Ñ from print to video to the Internet. Media literacy builds an understanding of the role of media in society as well as essential skills of inquiry and self-expression necessary for citizens of a democracy." (CML, 2003)

Within this definition

there is only a brief nod towards the idea of the creation of media as a component

of media literacy which is an indication of what I see as a under developed

aspect of the field. The Oxford

English Dictionary defines the term "literacy" as: "The quality

or state of being literate; especially the ability to read and write."

It is my opinion that Media Literacy as a field of study concentrates mainly

on the critical analysis and evaluation of existing media, or in other words,

the reading of media. The creation

or writing of media exists predominantly within a cultural industry production

model and not as a way of critically understanding a language of media. The

development of the Cycles of Iteration interface was inspired by a perceived

need to develop the "writing" aspect of media literacy.

Media literacy provides

a framework for a model of production that can exist outside of the model

dominated by the cultural production industry. With the exception of relatively

few guides for production of ethnographic (e.g. Barbash, 1997) or activist

video (e.g. Harding,

1997), the dominant model for

teaching video production is to give students the skills required to make

industrial forms of video such as dramatic scenes, title sequences, voice over

narrations, and news stories. This

adherence to the cultural industry model of production presents, in my view, a

restriction to the potential of a more general form of media communication.

Learning video production without the constraints of a cultural industry allows

the freedom of individual expression within the new language of media. To

become literate in this language one must be able to both read and write.

Advancing media

literacy is one of my goals as a teacher of media production. I believe that an

understanding of media production provides individuals with a greater ability

to make conscientious decisions in our increasingly mediated society. Raymond

Williams refers to choices that we as a society have concerning developments in

communication technology that can be a part of social development, social

growth, and social struggle (1974, p136). These choices are better made through

the demystification of media production that can lead to a greater

understanding of how public opinion is formed.

The formation of

personal and social identity is strongly influenced by the consumption of

cultural production such as film, television, Internet, and other media.

Marshall McLuhan theorizes that the dominant media of communication

historically shapes the progression of society and culture (1962, 1964). We

create boundaries that mystify or fetishize the production of mass media giving

its message a heightened value and as a result its impact on our identity as

citizens is increased. In order to

begin to break down these boundaries we must develop a form of literacy that

allows an understanding of cultural production. My experience as an instructor

has taught me that learning the process of media production is a significant

foundation to the advancement of Media Literacy.

Teaching media

production necessarily requires the instruction of a set of skills and

practices that often results in it being termed "vocational training" or

"skilling." At the base of my efforts to create resources for teaching video

production is a desire to educate students not only in practical skills but

also in critical understanding of the role media plays in society. In this regard I agree with Stan Denski

(1991) that an emphasis must be placed on the ethical and moral dimensions

involved in the structures and processes of media production as a practice

(dimensions that are largely ignored by traditional methods of media vocation

or "Industry" training).

Ethical and moral issues are not overtly addressed in the content of the Cycles of Iteration interface, however its design provides access to media production with as little beholding to industrial constraints as possible. The Cycles of Iteration interface was designed to maximize individual creativity and minimize equipment and resource constraints. There is as well a tacit understanding that the interface provides the skills training that frees up class time to critically discuss and analyze how the media production industry maintains and re-produces dominant cultural values. Allowing the possibility of creating alterative media productions.

Critical Pedagogy (toc)

A critical pedagogy of

media production is, in practice, a new concept. The bridging of media literacy with critical pedagogy

provides enormous potential for learning about how and why media has such an

impact on society. One of the

challenges of this bridging is the breadth of skills required to learn media

production can obfuscate less tangible inquiries of a moral or ethical

nature. This is a challenge of

practice that I have tried to address with the Cycles of Iteration interface by

allowing it to present and review the more objective and practical aspects of

production, something that a mediated interface is particularly good at doing.

Where as critical understanding of the roll of media production in the

construction of contemporary culture is a topic best taught in a non-mediated

dialogue.

Two specific

pedagogical theories were involved in the design of the Cycles of Iteration

interface that relate to video production as a social practice. Video production is inherently social

because its communicational properties require an audience; furthermore the

production of video often requires social interaction with co-producers (crew,

talent, etc.). The skills and procedures required to produce video make it an

experienced practice. These two

aspects, social interaction and experiential practice, are addressed in the

pedagogical theories of communities of practice by Etienne Wenger and the roll

of experience in education by John Dewey respectively.

Etienne Wenger proposes

a social theory of learning that is based on participation within a community of

practice. I have observed as a

media production instructor that one of the great motivators production

students have is the desire to be associated as part of the production industry

community. Even as critical

knowledge of the production industry is developed the desire to be accepted and

rewarded by the community of professional production is undeniable. This motivation can be viewed as a

challenge for media literacy and critical analysis but it can also serve as the

inspiration that facilitates learning and the construction of meaning. The

resulting situation is somewhat of a double-edged sword for a critical pedagogy

of media production requiring a balance between the motivational desires of

aspiring videographers and the development of critically conscientious media

producers and consumers.

The inter-subjective

nature of video production exists on a number of levels. One of the most noticeable

levels is the public presentation of finished works, or screenings.

Public screenings of student-produced videos are an accepted and important

part of learning the production process (see the Review sections in the Cycles

of Iteration interface). However, few other endeavours in most students

experience require the same level of public exposure, scrutiny, and critique. The fear of public review can be a powerful

motivator for any producer.

Another level of

inter-subjectivity in video production is related to its collaborative nature.

Although it is possible to produce video as an individual, a majority of production

requires some form of social interaction, such as instructing crewmembers,

directing talent, or securing permission to shoot a location. All such social

interactions become part of a community of practice that leads to the creation

of knowledge.

As presented in the

book "Communities of Practice" (Wenger, 1998) learning is a result of social

participation comprised of these components:

á

Meaning: a way of individually and collectively

experiencing our life and the world as meaningful. Meaning is ultimately what

learning is to produce.

á

Practice: shared historical and social frameworks

that can sustain mutual engagement in action.

á

Community: social configurations in which our

enterprises are defined as worthy and participation is recognizable as competence.

á

Identity: learning changes who we are and creates

personal histories of becoming in the context of our communities.

These components exist

in the community of practice that is formed by a group of video production

students and should be considered during the implementation of a media

production instructional environment.

Although John Dewey

(1859 - 1952) wrote in an era with less emphasis on the concerns we have today

about incorporating technology and media into learning environments, his

comments on "traditional" and "progressive" education are still valid. Traditional education relies on

institutionalized, historically defined subjects and methods, where as

progressive education requires a dynamic adaptation to a changing society. Dewey presents an argument that

requires education to be progressive (while not completely dismantling

traditional practices) not just because it improves the educational system but

because education in itself is a method of study by which we cumulatively

examine knowledge, meaning, and values of the world.

Michael Eldridge (1998)

describes the central aspect of Dewey's philosophy as "cultural

instrumentalism," a positioning that understands thinking to be a tool for

dealing with problems in the world. Dewey believed that the primary role of his

work was to develop this tool (thinking) to better society and its members, and

the key to doing this was through education. Education based on the "philosophy

of the social factors that operate in the constitution of the individual

experience" (Dewey, 1938). The factors, which he refers to as permanent frames

of reference, are the organic connection between education and personal

experience.

Dewey acknowledges that

experience is present in a learning environment regardless of design so what

really matters is the quality of experience. Two

aspects of the quality of experience should be considered. First the immediate

aspect of agreeable versus disagreeable experience, and secondly the influence

an experience has on subsequent experiences. An ideal learning experience is immediately enjoyable and

promotes having desirable future experiences. Therefore education is a development within by and for

experience. There is a continuity

or a "experiential continuum" in that every experience both takes up something

from those that have gone before and contributes to the quality of those to

come (Dewey, 1938).

Experience is essential

to learning the process of video production. The concept of "learning by doing"

is at the foundation of this entire mediated pedagogical design. Each cycle of

iteration is coupled with a practical module that is produced and reflected

upon (see the scenario building section for examples of practical

modules). The experience and

self-reflection that is gained from each iteration not only give practice to

concepts presented but also challenges areas of conceptual uncertainty by

forcing a concrete outcome (the finished production).

Design Theory (toc)

The term "Design" is used in

many different fields of study. Architects, graphic artists, landscapers,

fashion creators, system scientists, mathematicians, pedagogues, all claim

to be designers and to have a theory of design specific to their field. However,

the common idea that all theories of design address is the improvement of

future outcomes. To this end there is an emerging field of pure design studies

which attempts to integrate disciplines of understanding, communication, and

action with the intention of improving society's development by the humanization

of technological progress (Buchanan, 1996).

Design studies have

been emerging as form of integrating knowledge that combines theory and practice

to help negotiate the complexities of our current technological culture for

the better part of the 20th century. Walter Gropius inaugurated the Bauhaus

school for realizing a modern "architectonic" art in 1919, with

the guiding principal that design was "an integral part of the stuff

of life, necessary for everyone in a civilized society" and that it would

avert society's "enslavement by the machine" (Gropius, 1943). Design

still eludes a specific definition or even a set of accepted practices and

continues to grow in scope to what is now recognized as a "new liberal

art of technological culture." (Buchanan, 1996)

Attempts to systematize

a science of design have been made, such as Herbert A. Simon's book "The

Science of the Artificial" (1996). Simon presents methods and procedures

based on logic and analysis to suggest a system by which design problems can

be evaluated and ultimately solved. This approach, however, turns out to be

less effective in practice because of the multitude of indeterminable factors

that arise during the design process. A science of the artificial assumes

an almost perfect condition of human intentionality, a condition that as of

yet does not exist. As a result design remains an idiosyncratic domain that

lends itself to iterative structures, intuition, improvisation, and creativity

more so then to the scientific method.

An area of design

theory that was called upon during the development of the Cycles of Iteration

interface comes out of the field of Human Computer Interaction (HCI). Recent

trends in interactive systems research have indicated foundations for a new

design and analysis approach that draw upon developments, throughout the

twentieth century, in phenomenology and ethnomethodology. This foundational

framework is encapsulated in the concept of embodied interaction, developed in

particular by Paul Dourish (2001).

Embodied interaction is

a perspective that includes aspects of tangible and social computing by

accepting the act of interacting with technology as a part of a broader system

of meaning that is constructed from the specific settings (physical, social,

organizational, cultural, etc.) in which the action takes place. Embodied interaction is concerned with

how meaning is created, established and communicated through the incorporation

of technologies into practice. It exists as an organizing principal that has

been developed to inform the design and analysis of the interaction between

individuals and technology within a social context.

Using an embodied

perspective to view the pedagogical ideas of communities of practice and

experience allows the bringing together of two domains of knowledge and

practice, namely embodied interaction and critical pedagogy. The result is a movement towards a

theory that can inform the design of interactive pedagogical media.

Design studies have

produced a number of methods and procedures that can improve future outcomes.

The two specific methods used in the development of the Cycles of Iteration

interface were Scenario Building and Modelling.

Design Process (toc)

The first design

decision, after a problem statement and user profile had been decided, was the

medium for the interface. Initially the idea was to create an interactive DVD

that was menu driven and contained video and audio examples of concepts. The

reason for not perusing the DVD option was because the production requirements

were not justified for the level of instruction needed. The Cycles of Iteration interface is

designed for the novice student and most of the examples were as effective as

stills and text as they were with full resolution video and audio. However,

there are elements that could have benefited from video examples (i.e.

transitions in section 3c), therefore, the interactive DVD is still being

considered for future developments in pedagogical design. A "browser" based or

HTML based interface was decided on because of its ubiquitous nature and the

ease of development.

Initial design

prototypes included some larger video, image, and audio files with the

intention of the interface being served on local computers or from CD-ROM. The

added pedagogical value of the larger files was not significant enough to out

weigh the advantage of creating a centrally served web-based interface. The problem with the larger file on the

locally server version was that any updates would require re-loading the

interface on multiple computers. A centrally served web-based interface can be

updated from a single point and accessed from a web browser on any computer

with an Internet connection.

Whereas with a locally served interface the number of access points for

students is dramatically reduced.

Once the decision to create

a centrally served web-based interface was made the problem arose of reducing

file sizes so that access from slower network connections would still be

effective. A balance between effective communication and image compression

quality or image size was determined based on numerous test sites that were

examined using various network connections. The interface did not seem to be

effective unless there was almost instantaneous response to user interaction.

For a perceptibly instantaneous response the interface files had to be as small

as possible. This was achieved by maximizing image compression and the

extensive use of white space (which is more easily compressed) throughout the

site. The initial web-based interface that was used in the pilot study consisted

of approximately 450 files and is a total of 3.9 Megabytes.

Jakob Nielsen suggests

that size limits for web pages, in order to achieve a desired response time

(see latency times below), is between 8k and 100k (based on average ADSL home

internet connection bandwidth).

These limits provide the user with a sense that they are moving through

an "information space" freely (Nielsen, 1997). Almost all of the pages in the

Cycles of Iteration interface are between 8k and 24k, depending on the number

of images used, which provides adequate latency times to maintain user focus.

Nielsen states in his writings about usability engineering that his basic

advice regarding computer interface response times is: The faster the better

(Nielsen, 1994). A brief summary of how latency times affect the usability of a

web site are given here:

* 0.1 second is about the limit for having the user feel that the system is reacting instantaneously, meaning that no special feedback is necessary except to display the result.

* 1.0 second is about the limit for the user's flow of thought to stay uninterrupted, even though the user will notice the delay. Normally, no special feedback is necessary during delays of more than 0.1 but less than 1.0 second, but the user does lose the feeling of operating directly on the data.

á

10 seconds is about the limit for keeping the user's attention focused on the

dialogue. For longer delays, users will want to perform other tasks while

waiting for the computer to finish, so they should be given feedback indicating

when the computer expects to be done. Feedback during the delay is especially

important if the response time is likely to be highly variable, since users

will then not know what to expect. (Nielsen, 1994)

Donald A. Norman writes

extensively on the humanization of technology and design (see jnd.org). He

advises, in concurrence with Jakob Nielsen, that content and the speed with

which it arrives are the most important properties of a website. To this end

careful consideration should be given to graphics in that they should never be

gratuitous or in any way unrelated to the content of the website. Norman also

recommends that a website design should use HTML code that is as simple as

possible and to eliminate any graphical elements that do not directly add to

the informational content of the website (Norman, 2002). These admonitions were

used in the design of the Cycles of Iteration interface by reducing image size,

using graphics only to inform content, and keeping the HTML code to its

simplest reduction.

A significant challenge

to the creation of the Cycles of Iteration interface was the complexity and

volume of the content material. Careful attention was paid to the reduction and

simplification of content material to maintain the focus of the learning

objectives and not to confuse the user with too many specific or technical

details. Edward TufteÕs writings on designs for the display of information

provided many examples (both good and bad) that helped with the design of this

project (Tufte, 1983; Tufte, 1990; Tufte, 1997). Tufte emphasizes that design is choice, and that choices

should be made with grace, elegance and personal vision. TufteÕs epilogue in

The Visual Display of Quantitative Information:

What is to be sought in designs for the display of information is the clear portrayal of complexity. Not the complication of the simple; rather the task of the designer is to give visual access to the subtle and the difficult Ð that is, thel revelation of the complex (Tufte, 1983, p.191).

The structural model

for the Cycles of Iteration interface is the foundation that the entire design

is built on. The model is an expanding spiral that starts in the centre and

continues clockwise, expanding to a new level after each cycle. The concept behind the spiral structure

is to re-enforce the iterative nature of video production, and to represent the

idea that knowledge and skills are built upon knowledge and skills developed in

previous cycles.

To define what content

should be included in each cycle and in what order the information should be

presented, the method of scenario building was employed. Three scenarios were developed that

included a brief characterization of a potential user as well as the context in

which the interface might be used. In addition, three practical modules were

developed for each scenario that correspond to each of the three cycles in the

interface.

The development and

implementation of user scenarios was crucial to the interface design. The

scenarios, especially the practical modules, informed the content of the design

by providing sequential requirements of knowledge that would be needed to

complete each goal. The definition of the user modules was therefore the most

important component of the scenario building exercise.

File structure was an

important consideration in the design process from the onset. Ramifications of

organizational decisions concerning file structure that were made at the

beginning of the process would magnify as the number of files were added to the

design. The file structure had to

be able to maintain the organization of an unknown number of image and text

files, as a result the design of the first iteration had a couple of false

starts due to unwieldy file management.

The number of files could be expected to increase with consecutive

iterations (due to an increase in complexity of content with higher level

iterations) so if the file management system was hard to control in the first

iteration it was better to redesign the system before continuing. The resulting

file system combines a hierarchic structure and a nomenclature system that

reflects the overall structural design of the interface. Each iteration (1,2,3)

is divided into four quadrants (a,b,c,d) each of which have two sections

(concepts and slide show).

Development of a structural model (toc)

Hermeneutic cycle

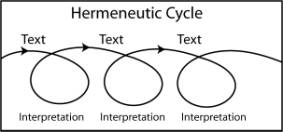

The hermeneutic circle

refers to the circle of interpretation that is involved in the understanding of

knowledge. The concept is a way of

stating that understanding and knowledge is a cycle of exposure to information

(texts), interpretation, then re-exposure to texts. Subsequent exposure to a text is influenced by the

interpretation of the previous text. This concept forms the foundation for the

structural model in the Cycles of Iteration design.

Figure 1 Hermeneutic Cycle

Hans-Georg Gadamer refers to a circular process of

hermeneutic interpretation where meaning is always negotiated between one's own

preconceptions and those within the horizon of the other (Gadamer, 1979). The

cycle exists between subjective knowledge and objective experience of a text.

Kitaro

Nishida uses a concept of "basho" to represent a place between subjective

and objective experiences. Knowledge is created in the space where subject

and object unite (Nishita, 1990). The union of the subject and the object

occur when a concept is internalized to the point of realization or practice.

It is the balance between explicit and tacit knowledge.

The structural model

for the Cycles of Iteration is an expanding spiral. Each iteration builds on

knowledge from the previous cycle.

Figure 2 Cycles of Iteration Structural Model

The design is intended

to imply expanding cycles that increase in complexity and are built upon

knowledge created in previous cycles. Each iteration is coupled with practical

modules (see the scenario building section) that allow the user to realize

concepts. The combinations of

presentation, review, and practice are inherent to the design as a method of

knowledge creation.

The cyclic form of the

structural design is divided into four quadrants. Each quadrant represents a stage in the production

process. Most established

textbooks state the first three stages in the production process, namely

Pre-Production, Production, and Post-Production (for example: Anderson, 1999;

Barbash, 1997; Hempe, 1997; Long, 2000; Rabiger, 1998; Zettl, 1995). However

the fourth stage, Review, is usually regarded as outside of the production

process. The reason I have

included a Review section as one of four elements in the production process is

because it serves a critical pedagogical purpose.

The Cycles of Iteration

structural design implies the continuation from ending one iteration to the

beginning of the next. The Review section allows a moment of reflection before

beginning the process again. This

reflection has the potential of teaching the producer about strengths and

weaknesses in their endeavours, ideas that seemed understood might not have

been communicated or intuitive actions during production may be explicitly

recognized. It has been my experience that public critique and evaluation

sessions of student productions have consistently been identified as one of the

most significant learning moments

(and sometimes the most difficult) in the production process.

The immediate experience that affects the design of the interface includes aspects such as speed of access, aesthetics (uniform, achromatic), ease of use, conceptual and navigational layout, etc. The allegorical nature of the structural design is meant to remind or make reference to previous experiences of the user. For example when a user is about to start the third iteration all four sections of the first two iterations are visible as reminders of lessons and practical skills that were learnt in past experiences. The intention is that these experiences will inform and inspire the participation in current and future experiences as they are presented in the model

Scenario Building (toc)

Scenario building is a

method of developing usability requirements or goals for a particular

design. Scenarios can be used to

identify and address implications of design options and interface issues that

arise during the initial design process (Carrol, 1995). Scenario building can help to inform

the design process about the way people may react to a design within a specific

situation.

During the initial

design process scenarios can provide a rich source of ideas by allowing

usability requirements and targets to be generated through the identification

of user characterizations. Scenarios offer concrete representations of design

requirements by defining intended end usersÕ identities, goals, tasks, and

their general working context (Clark, 1991).

The process of creating

design requirements using scenarios requires functionally deconstructing user

goals into the operations needed to achieve them. This is done by the creation

of "mental maps" that allow an insight into uncertainty by the development of

characters and stories (Schwartz, 1991).

The following are

scenarios were developed with the intention of providing a user insight into

the design of the pedagogical model. The scenarios are used to envision the

completion of three example modules that correspond to the cycle iteration in

the model.

Scenario 01 (toc)

Ted, 23, third year

Anthropology major at university. Moved to Vancouver four years ago from

Singapore. He is interested in learning video production to document an

archaeological dig he will be attending in Singapore next year. Ted has no

previous video production experience but is interested in computers and digital

photography. This scenario is based on conversations with undergraduate

students at Simon Fraser University.

Practical Modules:

Cycle 1: Scavenger

Hunt

A list of single shot

descriptions that include framing and movement indications (e.g. CU of someone

reading, MS of a financial transaction, WS of people waiting in a queue, PAN

across a crowd, etc.)

á

Time limit

for shooting (30-45 min)

á

Total time of

cycle (approximately): 2 to 3 hours

Cycle 2: Road

Trip

A sequence of scenes

depicting the journey from home to school are planned out in pre-production and

shot continuously and in sequence during production.

á

In-camera

edits

á

Limit of raw

footage (2.5 minutes)

á

Total time of

cycle (approximately): 1 day to 1 week

Cycle 3: Profile

Video portrait of

someone (class mate, relative, friend). Portrait can include interviews, visual

evidence and contextualization, audio layers such as music and narration.

á

One-minute

time limit of final video

á

Post-production

includes editing

á

Total time of

cycle (approximately): 1 to 3 weeks

Scenario 02 (toc)

Helen, 45, is an

assistant head day nurse at local general hospital. She has been a nurse at the

same hospital for 15 years. She

wants to learn some video production skills to be able to participate in a new

program that is archiving procedural video documentaries to help staff learn

how to use specific equipment. She

thinks the new program has a lot of merit but she is quite anxious about using

video and computer technology. This scenario is based on events that took place

during a workplace learning initiative that employed self-produced videos as

educational tools in a hospital intensive care unit. (Bjorgvinsson and

Hillgren, 2002).

Practical Modules:

Cycle 1: Equipment

shot list

A list of single shot

descriptions that include framing and movement indications (e.g. CU of power

switch, MS of the entire apparatus, WS of equipment in its location of use, PAN

from equipment to person operating it, etc.)

á

Time limit

for shooting (30-45 min)

á

Total time of

cycle (approximately): 2 to 3 hours

Cycle 2: Equipment

use preparation

A sequence of scenes

depicting the movement of equipment from storage to a location of use are

planned out in pre-production and shot continuously and in sequence during

production.

á

In-camera

edits

á

Limit of raw

footage (2.5 minutes)

á

Total time of

cycle (approximately): 1 day to 1 week

Cycle 3: Instructional

Video

Instructional video of

a piece of medical equipment in use, including operator and patient. Portrait

can include interviews, visual evidence and contextualization, audio layers

such as operator or patient commentary, equipment sounds and narration.

á

One-minute

time limit of final video

á

Post-production

includes editing

á Total time of cycle (approximately): 1 to 3 weeks

Scenario 03 (toc)

Steve, 17, is enrolled

in an inner-city program set up to assist youth. Video production is used by the program as a means of

empowering members and instructing them on issues like social justice,

responsibility and project management.

Steve likes video production because it makes him feel in control and he

likes it when people are impressed with his work. The administrators would like a set of videos that can be

used to orientate newcomers to the rules and policies of the program. Steve wants the task of producing this

set of videos but he lacks the skills. This scenario is based on conversations

with an instructor of video production for a similar program.

Practical Modules:

Cycle 1: Shot

list of scenes

A list of single shot

descriptions that include framing and movement indications (e.g. CU of a young

personÕs face, MS person sitting at a desk, WS of a class of youth all at

desks, PAN from class room to the exit, etc.)

á

Time limit

for shooting (30-45 min)

á

Total time of

cycle (approximately): 2 to 3 hours

Cycle 2: Accessing

the Facility

Sequence of scenes

depicting the journey from home to the facility are planned out in

pre-production and shot continuously and in sequence during production.

á

In-camera

edits

á

Limit of raw

footage (2.5 minutes)

á

Total time of

cycle (approximately): 1 day to 1 week

Cycle 3: Rule

#1

Short video that

informs newcomers to the facility about one of its rules (e.g. the rule that

only one person talks at a time that is designed to encourage listening and

facilitate communication). Video can include interviews, visual evidence and

contextualization, audio layers such as music and narration.

á

One-minute

time limit of final video

á

Post-production

includes editing

á

Total time of

cycle (approximately): 1 to 3 weeks

Outcomes and Evaluation (toc)

Evaluation Criteria

In 2000 a study was

conducted that identified a ranked list of evaluation criteria that could

assess the potential quality, appropriateness, and effectiveness of

instructional multi-media courseware. (Gibbs, 2000) The study used the Delphi

Process[2]

with a panel of instructional technology "experts" to rate a list of evaluation

criteria that was compiled from a literature review. For the study an expert

was someone who currently publishes, teaches, or is employed in the field of

computer-based courseware design, development or evaluation. The study

determined a list of 16 criteria, with an associated category (see Table 1),

that create a useful starting point for a pedagogical design and evaluation.

The questions that came

out of the "Identifying Important Criteria for Multimedia Instructional

Courseware Evaluation" study by William Gibbs (2000) were used as both criteria

to be adhered to while designing the interface and as a source of inquiry for

the students who were involved in the pilot study using the Cycles of Iteration

interface. Some of the questions are not applicable such as ones referring to

testing and feedback because the Cycles of Iteration interface does not include

these elements.

#

|

Category

|

Criteria |

|

1 |

Information Content |

Does the courseware provide accurate information? |

|

2 |

Information Reliability |

Are the answers provided to questions correct? |

|

3 |

Instructional Adequacy |

Are practice activities provided in the courseware to actively involve the learner? |

|

4 |

Feedback and Interactivity |

If a test is used, are test questions relevant to the courseware objectives? |

|

5 |

Clear, concise, unbiased language |

Are sentences written clearly? |

|

6 |

Evidence of Effectiveness |

Did learners learn from the courseware? |

|

7 |

Instruction Planning |

Is a definition of the target audience and prerequisite skills given in the courseware? |

|

8 |

Feedback and Interactivity |

Is feedback appropriate? |

|

9 |

Instructional Adequacy |

Are instructional objectives clearly? |

|

10 |

Support Issues |

Are the computer hardware and software requirements for the courseware specified? |

|

11 |

Information Content |

Are examples, practice exercises and feedback meaningful and relevant? |

|

12 |

Interface Design |

Is the courseware screen layout easy to understand? |

|

13 |

Instructional Adequacy |

Is the purpose of the courseware and what is needed to complete the lesson made explicit? |

|

14 |

Information Content |

Is the information current? |

|

15 |

Interface Design |

Do learners understand directions for using the courseware? |

|

16 |

Instructional Adequacy |

Does the courseware provide adequate support to help learners accomplish the lesson objectives? |

Table 1 Evaluation Criteria for Multimedia

Instructional Courseware (Gibbs, 2000)

Students in the pilot

study responded positively to questions about clarity of writing by making

statements like the interface instruction was "easy to understand" or "simply

laid out." The students checked the accuracy of the information to the extent

that they pointed out typing errors or other such mistakes, however

verification of content accuracy was better made by review by experienced video

instructors. The criteria that received mix reviews were based on clarity of

instructional objectives. Students

stated that the design of the interface was "too general" and that they would

like more examples that were specific to their assignments. To address this is

a matter of balance between creating a general interface that can be used in a

broad range of situations with one that addresses specific practical

modules. Comments about whether

the interface provided adequate support to accomplish objectives were helpful

in identifying areas that could be expanded on in the future. These comments

included specifics about confusing skills (such as importing and exporting from

and to video tape) as well as more general statements about formal design and

narrative structure (see cycle observations in the next section).

Pilot Study (toc)

Development of the

Cycles of Iteration interface was assisted using the process of a situated

design inquiry, or what might be called "design through use." Situated inquiry can be described as a:

"new framework for understanding

innovation and change. This framework has several key ingredients: It

emphasizes contrastive analysis and seeks to explore differences in use. It

assumes that the object of study is neither the innovation alone nor its

effects, but rather, the realization of the innovation--the innovation-in-use.

Finally, it produces hypotheses supported by detailed analyses of actual

practices. These hypotheses make possible informed plans for use and change of

innovations." (Bruce & Rubin, 1993, p. 215)

Users (in this case

students) participate in the design development by their contributions of

content suggestions and evaluations of the design's usefulness. The methods employed include a pilot study

of an implementation of the interface in which interviews and participant

observations were done to asses the level at which the design meets the specific

needs of the students. This study used situated evaluation as a way to examine

the interaction between a newly developed mediated pedagogical design and

the specific, contextual and experiential circumstances of a group of users.

The Cycles of Iteration

interface was pilot tested using a group of 24 undergraduate students enrolled

in a Communication course entitled "Introduction to Digital Video." The course was offered at a second year

level with no production experience required. An initial survey of the students

indicated that only two of them had any video production experience. The intention

of the pilot study was to gather feedback and observations of end users while

the interface was still being developed in order to inform its design rather

than to make an evaluation of a final product. Although, an evaluation of

the design could be extracted from the information gathered.

Students enrolled in

the class were asked to participate in a research project to help design the

pedagogical resources that would be part of the course. All students agreed to

participate and were given an informed consent form (see Appendix A) indicating

what participating would involve and contact information for registering any

complaints or questions in accordance to Simon Fraser University Research

Ethics policy.

The design of the

Cycles of Iteration interface allows for more complex issues to be presented

with subsequent iterations. This results in more time required to complete

higher-level cycles. The following table gives the time requirements needed to

present each cycle and complete the related module during the pilot study.

|

Cycle |

Presentation of Material |

Completion of

Module |

Dates |

|

Cycle 1 |

Pre Ð 10 min Pro Ð 20min Post Ð 5min Review Ð 5min Total Ð 40min |

Production Ð 60min Screening Ð 60min |

January 6, 2003 Total time Ð one day |

|

Cycle 2 |

Pre Ð 60min + discussion (20min) Pro Ð 15min |

Pre-Production With some Production Ð 1Week |

January 13, 2003 |

|

Pro Ð 40min Post Ð 30min |

Production and Post-Production Ð 1Week |

January 20, 2003 |

|

|

Review Ð 20min Total Ð 3hours |

Screening Ð 2hours |

January 27, 2003 Total time Ð 2Weeks |

|

|

Cycle 3 |

Pre Ð 20min part 1 |

Pre-Production Ð 1Week |

January 27, 2003 |

|

Pre Ð 2hours part 2 Pro Ð 40min |

Production Ð 1Week |

February 3, 2003 |

|

|

Post Ð 2hours + 30min for questions |

Post-Production Ð 1Week |

February 10, 2003 |

|

|

Review Ð 20min Total Ð 5.8hours |

Screening with critique Ð 4hours |

February 17, 2003 Total time Ð 3Weeks |

Table 2 Dates and Times for completion of each practical module

Observations of how students

reacted to the presentation or slide show portion of the Cycles of Iteration

interface were recorded in the form of field notes that were made at the end of

each week. In addition to

observations, informal questions were asked of the students about what they

remembered most from last weeks presentation and about what additional content

could have been included to assist the completion of each practical module.

The following is a summary of my observations and student comments that could be incorporated into the interface design.

Cycle One (toc)

Pre-production

á

Orientation

of videotape when inserting it into the camera was not clear for some.

Post-production

á

People who

have any trepidation about connecting video equipment were shy to try in front

of the class and would leave the task to people more familiar with it. VCR

connections should be part of the practical module.

Review

á

Allow plenty

of time for review.

á

The practical

module was not fully understood by all students, so a more precise description

is needed.

Cycle Two (toc)

Pre-production

á

Narrative

structure is difficult to understand, more examples and diagrams would be

helpful

á

Some acoustic

examples for the equipment section would help demonstrate the microphone.

Production

á

A visual

image of a Videographer, showing mic, camera, headphones, etc., would help

define the term.

á

Correlations

between shot composition and the resulting meaning is needed, for example high

angle shot means a diminutive shot.

á

The

production quadrant should be given in the first week but the pre-production

quadrant seemed too long.

Post-production

á

Explanation

on how to use the interface simultaneously while using editing software on a

computer was not understood by all the students

á

Comments

students made while editing (problems they had trouble solving)

á

Focus lesson

needed earlier

á

Drag-and-drop

audio file icon

á

Waveform

display in sequence preferences

á

Rubberband

on/off

á

Visual Audio

editing

á

AV

preferences for FireWire vs. Desktop display

á

Recording

output to camera (VTR, record)

Review

á

All 12

assignments were done on time and on tape ready to present (it has never

happened before that all first assignments are done on time without

intervention).

á

Overview of

Review process including evaluation and critique criteria and framework took

about 20 min.

á

Screening of

all 12 pieces took about 2 hours

á

Lively

discussion followed the screening of each piece. Students are very happy to talk about their own work and

work of other peers. Critique session is a great chance to interact and debate

issues of perception, audience reaction, levels of communication, salience of

concepts, etc.

Cycle Three (toc)

Pre-production

á

Long time to

explain (2 hrs. for pre-), lack of slides makes this section a little dry.

á

Using

descriptions of characters as a way to demonstrate on-screen persona, important

for interviews.

Production

á

Actual

demonstration of interview setup reviled how important pre-production concepts

are.

á

A lot of

confusion and indecision made for some less than satisfactory compromises on

the shots.

á

Too much time

spent trying to fix problems.

á

Lacked the

Affect due to no pre-production planning

á

Make the

pre-production part of the exercise

á

Have the

proposal, research, and treatment done before the interview in the exercise.

Post-production

á

Questions and

comments from users. (Issues that were difficult to understand)

o

How to use

the Iris controls

(Production)

o

Explain rendering

o

What is a cross-dissolve

(video example?)

o

Explain file management

á

Only works

when in conjunction with the live demo.

Interaction would be improved by having both interfaces at once.

á

This level of

lesson requires presenting, demonstrating, trying, reviewing, re-trying, doing.

á

Mention about

monitoring your production, making VHS dub to watch on your regular Television

to give a "calibrated" reference.

Review

á

This project

is very personal and caution must be taken against insulting or upsetting

producers.

á

Variations on

self contained movie files and title frames (main mistake was 22 KHz audio, and

format inconsistencies with still image).

á

Wide range of

productions, the best seemed to adhere to a narrative structure or aesthetic

design.

á

Future cycles

in pre-production should include aesthetic design

á

Presentation

can include web based delivery

á

Include web

stats on site hits as a "ratings" measure.

á

Students are

very interested in seeing their own work on a web site.

á

Almost 4

hours to screen and critique all 24 projects.

Expert Panel (toc)

In addition to the

pilot study the Cycles of Iteration interface was sent to a number of "experts"

who are or have been employed professionally in the field of instructing video

production. The responses from

this expert panel were intended not only to provide constructive criticism on

the interface but also to elicit new ideas for content and design based on

their experience in this area. Each expert was given the URL for the Cycles of

Iteration interface along with a brief description of the project and an

example of practical modules that could be used for each iteration. Feedback from these experts was

gathered from interviews (in-person or by telephone) or from emailed comments.

The comments from the

expert panel agreed that the content of the Cycles of Iteration interface was

accurate and clearly presented.

There were some suggestions that the attempt to create a general

interface that could be used by a broad range of users was both a strength and

a weakness in the design. It was

suggested that the model (expanding spiral) was a good general design but as

each iteration increased in complexity more specific information is required,

which works against the idea of a general interface. Other suggestions related to this were that general

information and specific information be separated so that the interface is

based only on the general but spaces are made to "plug in" specific

modules. The nature of video

production necessarily requires very specific instruction based on equipment,

software, and the uniqueness of the production itself. This necessity was

balanced with a criteria set out in the problem statement for this design that

was to make a general interface for advancing novice Videographer. Strategies

to address this balance between generality and specificity would be one of the

first areas to address in future re-designs of this interface.

A suggestion that came

out of the expert panel was to create a separate page that contained links to

other related web sites. This would provide users interested in related topics

a starting point for further research, as well as give students the impression

that the area of video production can be quite vast and open-ended. Another recommendation was to break

down the script writing section to include sections on "the idea" and "the

outline" as a way to build up to an actual script.

Web Statistics (toc)

Weekly statistics of hits

to the web host site were accumulated over the time of the pilot study. These

statistics can show some of the general patterns of use on the Cycles of

Iteration web site. The site was

not activated until the week ending with January 24th. At this time

the pilot study group was into their cycle 2 project, the Road Trip. Prior to

this time the site was used as a presentation or on a single computer for

reference. The completion time for the first cycle (one day) does not allow for

much review. The consistent number of hits on the first and second cycles right

through to end of the pilot study (April 4th) could indicate the

review process happening as intended by the design.

Figure 3 Hits on the Cycle of Iteration web site

for duration of Pilot Study (Dates represent the end of that week)

The dramatic increase

in hits that occur in the week ending March 7th is due to a mid-term

exam that was given that week.

This peak of activity does not reflect how the site was intended to be

used but it does show the undeniable importance university students place on

exams.

It should be noted that

the designed use of the Cycles of Iteration interface intergrates modes of

presentation and review. The data for site hits represents only the review

mode within the context of the undergraduate university student. Also, many

students preferred to print a hard copy of the concept pages for each cycle

and refer to that rather than going back to the web site.

Figure 4 Hits, Unique Hosts, Unique URL's for duration of Pilot Study (dates represent the end of that week)

With the exception of

the mid-term exam peak there seems to be a contrapuntal relationship between

the total /cycle hits and the Unique URLÕs. This represents more activity

on fewer pages. The number of unique hosts accessing the /cycle site showed

a slight increase during the pilot study.

Figure 5 Hits for the top pages for each quadrant.

The pages that

contributed most to this increase of activity are:

1.

Cycle 1a.

Pre-production, first iteration, introduction to basic camera use and shooting.

2.

Cycle 2c.

Post-production, second iteration, digitizing footage, still frames, adding

audio.

3.

Cycle 3c.

Post-production, third iteration, assemble editing, insert editing,

transitions, titles.

Discussion and Conclusion (toc)

The process of

developing the Cycles of Iteration interface has been an exploration into both

the practical challenges of mediated pedagogical design and the theoretical

reasoning for attempting to advance media literacy. One of the main ideas behind this interface is that a

critical understanding of mediaÕs roll in society is enhanced by a personal,

practical knowledge of its production. The intention of the Cycles of Iteration

interface has never been to just supply an educational resource for video

production; rather it has been to create a system that can enhance an

instructor lead study into how media can construct and influence our

culture. This intention can only

be realized by the conscious practice on the part of the instructor to

emphasize a critical analysis of media and its influences on society. The Cycles of Iteration interface can

free up an instructors time and effort to make that emphasis possible. Its

modular and generalized structure makes it possible for it to be incorporated

as a component to a variety or more "theoretical" curricula. Furthermore, the

iterative nature of the interface design allows for theories to be introduced

and then revisited at each subsequent iteration.

The idea of building a theoretical understanding upon practical knowledge can allow a form of media literacy that reduces the separation between a purely academic critique and the isolated tradition of training for the culture industry. In addition this combination of theory and practice provides an important access point for students because it can use forms of popular culture they are already familiar with and it allows an outlet for their personal expression. As Stanley Aronwitz points out,

"Écritical work without an effort to produce popular art forms remains a peculiarly intellectual take on cultural life which is already distant from the experience of students. What I am saying is this: There can be no cultural pedagogy without a cultural practice that both explores the possibilities of the form and brings out studentsÕ talents." (1989, p.201)

My experience of

teaching video production has brought into question a division between the

practice of production and the analysis of media as critical area of

study. The dependence on

technology and the domination of a professional production model entrench a

division between the practice of production and a critique of the media

product. My difficulty with this inherent division is echoed by what David

Sholle and Stan Denski refer to as "feelings of schizophrenia" (1994, p.7). A

dichotomy is formed when you teach to create what you are teaching to critique.

Sholle and Denski suggest, "building bridges" across this separation by placing

production within an "integrated curriculum" (1994, p.171). This form of

integration of production with theory is part of the intention behind the

design of the Cycles of Iteration interface.

The task of bringing

together the production practice with the critical theory is daunting, but the

potential rewards are great. The

insights gained by a personal, practical awareness of production in combination

with a critical theory that contextualizes media socially, politically and

economically far outweigh the inherent challenges. The goal is to move towards

an applied pedagogy that blends "learning to do" with

"learning to critically understand" (Kline, 2002).

The idea of

using the popular product of the culture industry as a pedagogical device has

long been a vision of educators (see Crandall, 1926). However, professional

modes of media production have demanded resources that were out of reach most

education environments. Only recently with the advent of Digital Video (DV)

technology has it become feasible to integrate production into other forms of

learning. In many cases the computers students are using to type essays and

check email are sufficient to edit video as well. The accessibility of video

production technology is a major factor in the argument for incorporating

production into existing media analysis curricula.

The process

of developing the Cycles of Iteration interface was both challenging and

informative. It is a pursuit that has no final product only a small

contribution to what can be done or improved on in the future. The most important thing I learnt from

this development process is that incorporating technologically based teaching resources

into the learning environment does not diminish the roll of the instructor.

Mediating the learning process with technology can be very helpful with many

practical aspects of production. Technical specifications, checklists,

examples, and the like are well suited to an interface such as the Cycles of

Iteration. However, the real

synergy between theory and practice comes with a combination of practical

skills with critical analysis, discussion, and reflection. This combination can assisted with

mediated pedagogical resources but can only be realized in conjunction with

traditional forms of learning that involve a dialog between teacher and

learner.

The Cycles

of iteration interface was an extremely helpful resource for teaching video

production. It has provided a framework for the future addition of much more

information and examples. However, the real challenge for future development is

how to integrate practical production skills into a curriculum of critical

media analysis. The Cycles of Iteration interface represents only the beginning

of this challenge.

Appendix A: Informed Consent form (Pilot Study) (toc)

Informed

Consent By Subjects to Participate In a Research Project

The University

and those conducting this project subscribe to the ethical conduct of research

and to the protection at all times of the interests, comfort, and safety of

subjects. This research is being conducted under permission of the Simon Fraser

Research Ethics Board. The chief concern of the Board is for the health, safety

and psychological well being of research participants.

Should you wish

to obtain information about your rights as a participant in research, or about

the responsibilities of researchers, or if you have any questions, concerns or

complaints about the manner in which you were treated in this study, please

contact the Director, Office of Research Ethics by email at hweinber@sfu.ca or

phone at 604-268-6593

Your signature on this form will signify that you have received a document which describes the procedures, possible risks, and benefits of this research project, that you have received an adequate opportunity to consider the information in the documents describing the project or experiment, and that you voluntarily agree to participate in the project or experiment

Name of

Experiment: Pedagogical

Design: Cycles of Iteration case study

Investigator

Name: David

C. Murphy

Investigator

Department: Communication

Having been asked

to participate in a research project or experiment, I certify that I have read

the procedures specified in this document, describing the project or

experiment. I understand the procedures to be used in this experiment and the

personal risks, and benefits to me in taking part in the project or experiment,

as stated below:

Risks and

Benefits: There is no perceivable increase in risk by participating in this

study. Benefits to participating include experience of a research method in

practice.

I understand that

I may withdraw my participation at any time. I also understand that I may

register any complaint with the Director of the Office of Research Ethics or

the researcher named above or with the Chair, Director or Dean of the

Department, School or Faculty as shown below.

Dean of Applied

Science: Dr.

Brian Lewis

Director of

Research Ethics: Dr.

H. Weinberg

8888 University

Way, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia, V5A 1S6, Canada

SIMON FRASER

UNIVERSITY

I may obtain

copies of the results of this study, upon its completion by contacting:

David C. Murphy

(davidcot@sfu.ca)

I have been

informed that the research will be confidential to the full extent permitted by

the law.

I understand that

my supervisor or employer may require me to obtain his or her permission prior

to my participation in a study of this kind.

Participants will

be asked to contribute to a situated inquiry project testing a pedagogical

model. They may be asked questions in interviews and questionnaires and will be

observed during their participation.

ParticipantÕs

Full Name:

ParticipantÕs

contact information:

Date:

___________________________________ ____________________________

ParticipantÕs Signature Witness Signature

APPendix B: : Informed Consent form (Expert Panel) (toc)

INFORMED

CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE IN THE

PEDAGOGICAL MEDIA DESIGN ASSESEMENT RESEARCH PROJECT

The University and those conducting this project

subscribe to the ethical conduct of research and to the protection at all times

of the interests, comfort, and safety of subjects. This form and the information it contains are given to you

for your own protection and full understanding of the procedures. Your

signature on this form will signify that you understand the procedures,

possible risks, and benefits of this research project, that you have received

an adequate opportunity to consider this information, and that you voluntarily

agree to participate in the project.

Any information that is obtained during this study will

be kept confidential to the full extent permitted by law. Knowledge of your identity is not

required. You will not be required

to write your name or any other identifying information on the research

materials. Materials will be held

in a secure location and will be destroyed after the completion of the

study. However, it is possible

that, as a result of legal action, the researcher may be required to divulge

information obtained in the course of this research to a court or other legal

body.

The procedure for the Pedagogical Media Design

Assessment research project will entail access to a prototype of the

Pedagogical Media Design Interface followed by an in-person interview that will

assess the efficacy of the interface.

Having been asked by David Murphy of the School of Communication of Simon Fraser University to participate in

a research project experiment, I have read the procedures specified in this

document.

I understand that I may withdraw my participation in

this experiment at any time.

I also understand that I may register any complaint I

might have about the experiment with the researcher named above or with Dr.

Brian Lewis, Dean of the

Faculty of Applied Science of Simon Fraser University.

I may obtain copies of the results of this study, upon

its completion, by contacting: David Murphy (604-291-3623 or davidcot@sfu.ca)

I have been informed that the research material will be

held confidential by the Principal Investigator.

I understand that my supervisor or employer may require

me to obtain his or her permission prior to my participation in a study such as

this.

I agree to participate by responding to interview

questions asked by the Principal Investigator.

During a time period (within the dates of May 22, 2002

and August 30, 2003) and at the location to be agreed upon with the Principal

Investigator. Interviews can be

done over the telephone. The

interviews will not be

audio recorded.

NAME (please type or print legibly): _____________________________________

ADDRESS:

SIGNATURE:

_______________________ WITNESS: ______________________

DATE:

Appendix C: Starting Instructions (toc)

Starting

instructions for the Cycles of Iteration

The site structure

starts with the Cycle home symbol

Each cycle begins

with the Pre-Production quadrant

located at the top

right. Clicking on a quadrant takes

you into that

module:

Each module is

divided into two modes:

1.

Concepts Ð

textual based, vertically orientated

2.

![]()

![]() Slides Ð image based, horizontally

orientated

Slides Ð image based, horizontally

orientated

![]()

![]()

Use the arrow

symbols to move up or down through

the concepts, or

forward or back through the slides

The Cycle symbol

will always take you back to the

previous level.

Shading indicates

your current level

(this example is 1a)

(this example is 1a)

The Index pages

show a complete cycle on one page.

References (toc)

Anderson, G. H. (1999). Video Editing and

Post-Production: A Professional Guide. Boston: Focal Press.

Aronowitz, S. (1989). Working-Class Identity and

Celluloid Fantasies in the Electronic Age. In H. A. Giroux & R. Simon

(Eds.), Popular Culture, Schooling and Everyday Life (pp. 197-218). Granby, Mass.: Bergin &

Garvey.

Barbash, I., & Taylor, L. (1997). Cross-Cultural

Filmmaking: A Handbook for Making Documentary and Ethnographic Films and Videos. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bjorgvinsson, E. B., & Hillgren, P.-A. (2002). Readymade

Design at an Intensive Care Unit. Paper presented at the Participatory Design Conference, Malmo, Sweden.

Buchanan, R. (1996). Wicked Problems in Design

Thinking. In V. Margolin & R. Buchanan (Eds.), The Idea of Design. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Carrol, J. M. e. (1995). Scenario-Based Design. London: John Wiley & Sons.

Clark, L. (1991). The Use of Scenarios By User

Interface Designers. Paper

presented at the HCI'91.

CML. (2003). Media Literacy: A Definition...and

More. Retrieved March 5,

2003, from http://www.medialit.org/reading_room/rr2def.php

Crandall, E. L. (1926). Possibilities of the Cinema in

Education. The Annals, 128,

109-115.

Denski, S. W. (1991). Critical Pedagogy and Media

Poduction: The Theory and Practice of the Video Documentary. Journal of Film

and Video, 43(3).

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and Education. New York: Collier Books.

Dourish, P. (2001). Where the Action Is: The

foundations of Embodied Interaction. Massachusettes: MIT Press.

Eldridge, M. (1998). Transforming experience : John

Dewey's cultural instrumentalism. London: Vanderbilt University Pres.

Gadamer, H.-G. (1979). Truth and Method (W. Glen-Doepel, Trans. 2nd edition ed.).

London: Sheed and Ward.

Geuens, J.-P. (2000). Film Production Theory. New York: State University of New York

Press.

Gibbs, W. J. (2000). Identifying Important Criteria

for Multimedia Instructional Courseware Evaluation. Journal of Computing in

Higher Education, 12(1),

84-106.

Gropius, W. (1943). Scope of Total Architecture (Vol. 3). New York: Harper and Row.

Hampe, B. (1997). Making Documentary Films and

Reality Videos. New York:

Henry Holt & Co. Inc.

Harding, T. (1997). The Video Activist

Handbook.

London: Pluto Press.

Kline, S. (2002, November). E-mail correspondence.

Linstone, H. A., & Turoff, M. (Eds.). (1975). The

Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications. Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley.

Long, B., & Schenk, S. (2000). The Digital Filmmaking

Handbook. Rockland, Mass.:

Charles River Media Inc.

Lusted, D. (1986). Why Pedagogy? Screen, 12, 2-15.

McLuhan, M. (1962). The Gutenberg Galaxy: The

Making of Typographical Man.

New York: McGraw-Hill.

McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding Media: The Extensions

of Man. New York:

McGraw-Hill.

Nielsen, J. (1994). Usability Engineering. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann.

Nielsen, J. (1997). The Need For Speed. Retrieved April, 2003, from

http://www.useit.com/alertbox/9703a.html

Nishida, K. (1990, Trans.; 1921, Original). An

Inquiry Into The Good (M.

Abe & C. Ives, Trans.). Chelsea, Michigan: Yale University Press.